This post is part of a series on Huawei in Europe:

Huawei’s Christmas battle for Central Europe, by Jichang Lulu and Martin Hála (28 Dec 2018), also published on China Digital Times.

A new front opens in Huawei’s battle for Central Europe, by Sinopsis (12 Jan 2019).

The importance of Friendly Contacts: the New Comintern to Huawei’s rescue, by Sinopsis and Jichang Lulu (24 Jan 2019), cf. A New Comintern for the New Era: the CCP International Department from Bucharest to Reykjavík, by Jichang Lulu and Martin Hála (16 Aug 2018).

Arresting Huawei’s march in Warsaw, by Łukasz Sarek (2 Feb 2019).

Lawfare by proxy: Huawei touts “independent” legal advice by a CCP member, by Sinopsis and Jichang Lulu (8 Feb 2019).

Sinopsis’ Czech-language coverage of Huawei here.

An invitation-only presentation by Huawei last week demonstrated the company remains committed to one of the pillars of its legal and information strategy: to “normalize” itself for foreign eyes by creating a perception of endorsements by foreign entities and individuals. Notably, the recycling of a “confidential” and utterly “independent” legal opinion from an “outstanding lawyer Party member”, first reported by Sinopsis, is now complemented by a (presumably supportive) report commissioned from a Western accounting firm.

In the Party-state’s image

Huawei has gone to considerable lengths to portray itself as a peer of foreign tech giants, seeking to erase the relevance of its integration with the CCP-led political, military and economic system. To amplify its message in local discourse, it has recruited former senior civil servants and politically-connected individuals as executives in the UK, Australia and, most recently, Poland, where it has hired a former aide of PM Morawiecki. Such hiring practices may increase the company’s “discursive power” (话语权) on the ground, yet at the same time raise suspicions that this may not quite be the personnel policy of the regular private firm Huawei would like to present itself to be.

In Australia, Huawei was the top corporate sponsor of parliamentary trips between 2010 and 2018. A Western Australian minister under whom controversial Huawei deal was negotiated had let the company cover part of his expenses for a China trip while in opposition. The company has invested in think-tank sponsorship, notably with Chatham House and the Brookings Institution.

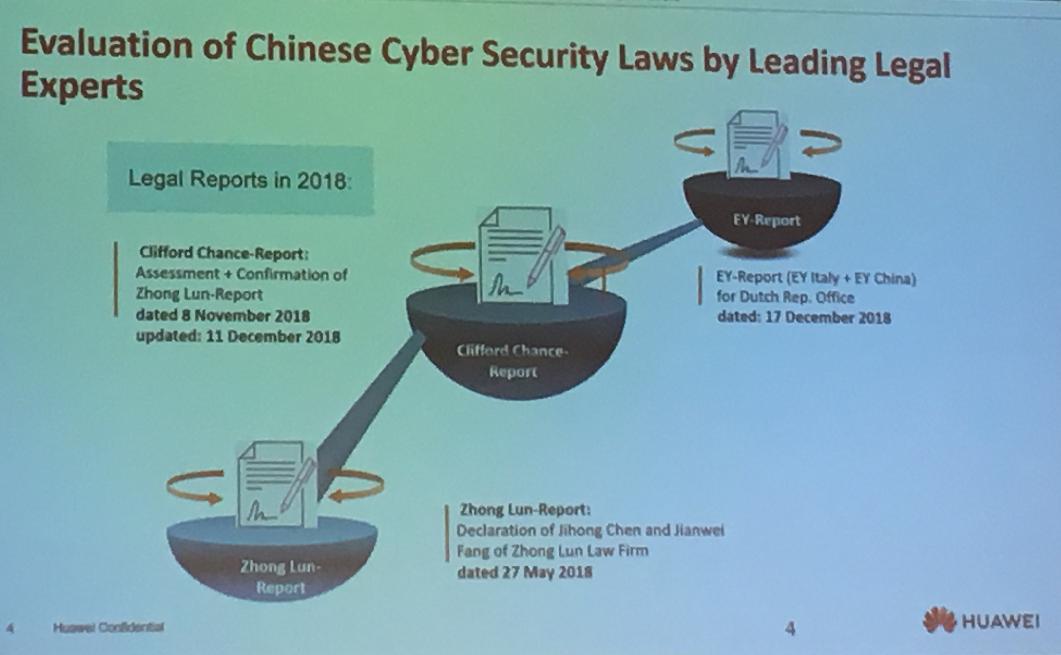

In Central and Eastern Europe, a crucial battleground since the November warning by Czech cyberintelligence against the use of Huawei equipment in critical infrastructure, the company deployed a further “foreignized” weapon. Huawei had a Chinese legal opinion it had used in its defense in the US and Australia reviewed by Clifford Chance, a British law firm with extensive operations in China, and took to invoking it in media and other communications, at times misrepresenting the foreign review as an “independent legal opinion”.

A Sinopsis analysis of the document and its background, available through multiple outlets in English and Czech, established the somewhat convoluted evolution of the document, perhaps limiting the impact of this “foreignized” tool in the country. It was, however, taken elsewhere: nearly a month later, Zhou Hanhua 周汉华, a senior legal scholar with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, took a break from his more regular topics like “strengthening the Party’s leadership over the work of ruling the country by law in an all-round way”, and used a US tech news website as a “borrowed boat” to channel an oped about Huawei’s independence, once more invoking the “foreignized” legal document. Again, the analysis failed to convince local experts.

Donald Clarke, a George Washington University professor who specializes in Chinese law, produced a memorandum on the Zhong Lun document, which he found to be “misleading and in places inaccurate”.

It is misleading because it misstates the key question of concern to the United States and other governments. That question is not what Chinese law says about the ability of the Chinese government to tell companies like Huawei what to do. The question is what the Chinese government can actually do, regardless of what the law might say. The [Zhong Lun] Declaration does not address the key issue of whether the Chinese government is meaningfully constrained by Chinese law.

Discourse management through mistranslation

Ondřej Klimeš has noted the similarity between Huawei’s “lawfare” and PR and legal and information warfare as components of the People’s Liberation Army Three Warfares doctrine, which has also been applied beyond the military:

Huawei’s manipulation can be regarded as a manifestation of the so-called public opinion warfare (舆论战), one of the three strategies in the Chinese hybrid-warfare concept known as the Three Warfares (三种战法), formulated by Chinese military strategists in the late 1990s and officially integrated into PRC war doctrine in 2003. On the other hand, Huawei’s letter to the [Czech cybersecurity agency] NÚKIB, anticipating the company’s possible legal measures against the Czech Republic unless it annuls the NÚKIB warning should be filed under the second strategy, legal warfare (法律战).

Huawei’s “foreignized” recruitment and communications practices also resemble the ways of the Party-state.

Anne-Marie Brady, whose 2003 book on the CCP’s “foreigner management” invoked Mao Zedong’s admonition to “make the foreign serve China” (洋为中用), notes Xi Jinping’s use of the motto in her 2017 study of contemporary international United Front work. Huawei’s tactics appear in accord with a policy of

[a]ppoint[ing] foreigners with access to political power to high profile roles in Chinese companies or Chinese-funded entities in the host country

as well as

[c]oopt[ing] foreign academics, entrepreneurs, and politicians to promote China’s perspective in the media and academia. Build up positive relations with susceptible individuals via shows of generous political hospitality in China.

As noted in a recent Sinopsis policy brief, the CCP’s presentation of its unique tactics and initiatives as equivalent to regular practices of target countries often relies on “discourse management through mistranslation”:

Western mistranslation phenomena, exploited by the PRC’s external propaganda, are also relevant to the Huawei case: analyses limited to technical aspects are insufficient unless informed by a knowledge of the political environment inhabited by such companies as Huawei.

To the foreign actors engaged for its “mistranslation” work, Huawei can now add a “Big Four” accounting firm.

Waltzing with Huawei

On March 14, at a closed-door event outside the Vienna Cyber Security Week program, Huawei executives presented their company once again as a private and “employee-owned”.

Presenters included Mika Lauhde, a senior cybersecurity expert formerly with Nokia whose move to Huawei appears to have triggered worries about his participation in EU structures: according to a Wirtschaftswoche report, French and German concerns led to quiet indications that he should quit his post at the European Network and Information Security Agency (ENISA). (As the report notes, Lauhde’s name does not appear in the updated member list of the ENISA Permanent Stakeholders Group, to which he was appointed for the 2017-2020 period.)

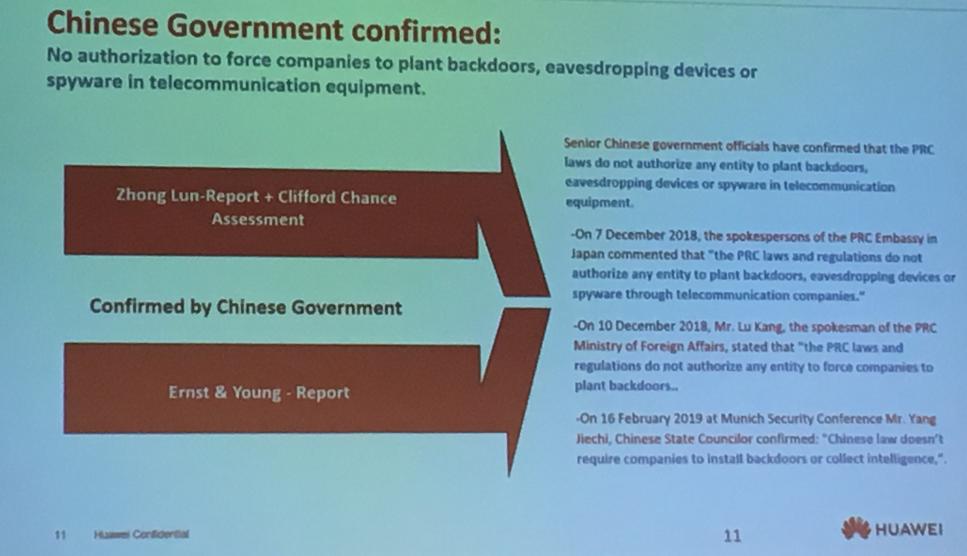

Huawei’s legal department offered a presentation on Chinese cyber security laws, arguing once again that Huawei is not obliged by law to cooperate with PRC intelligence in any of a number of possible ways, and that it would “categorically refuse” to comply with a request to do so.

To the previously deployed Clifford Chance review (which explicitly states it “should not be construed as constituting a legal opinion on the application of PRC law”), Huawei now has seemingly added a report by the China and Italy offices of accounting firm Ernst & Young.

As on previous occasions, the ultimate witness validates Huawei’s contention: the PRC government itself.

The combined endorsements of Beijing Zhong Lun Law Firm, Clifford Chance, the leader of the Czech Communist Party, Professor Zhou Hanhua, President Miloš Zeman and the PRC government itself have so far failed to bring about a universally welcoming attitude towards Huawei in Europe. If anything, the company’s continued use of “foreignization” as a tool provides an example of the uncanny similarities between the methods of state and non-state entities in the Party-led system.