In the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, also known as East Turkestan, the emerging testimonies of human rights abuses reveal practices of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) which could arguably constitute crimes against humanity. Since 2017, news outlets and human rights groups have been unearthing evidence of detention centers for ethnic minorities. Accounts, reports, and research have prompted the United Nations to bring this situation to the world’s attention when its Committee on the Elimination for Racial Discrimination (CERD) referred in August 2018 to reports that up to one million ethnic Uyghurs (and other minorities) were held in ‘re-education’ facilities. Many of these detainees are held for extensive periods of time, without trial or legal representation, and mostly incommunicado. For many relatives of detained Uyghurs, the processes of detention are often obscured, yet signaling arbitrariness and rights violations.

Aziz Sulayman, now residing in the United States since August 2009, does not know where his younger brother, Alim, is held. In June 2016, Aziz’s sisters told him on the phone that Alim had been sentenced without trial to ten years in prison, either due to his travel to Turkey or for allegations of attending meetings of the Uyghur Academy, an international association of Uyghur intellectuals. Both travel and intellectual activity can be considered ‘religious extremism’ by the Chinese authorities.

When Aziz attended a protest against the CCP’s treatment of Uyghurs in front of the European Commission building in Brussels on 27 April, 2018, he met a friend of Alim’s. The friend confirmed Alim was sentenced to ten years and sent to a prison in Korla. The train line between Golmud and Korla connects Xinjiang to the larger area of China.

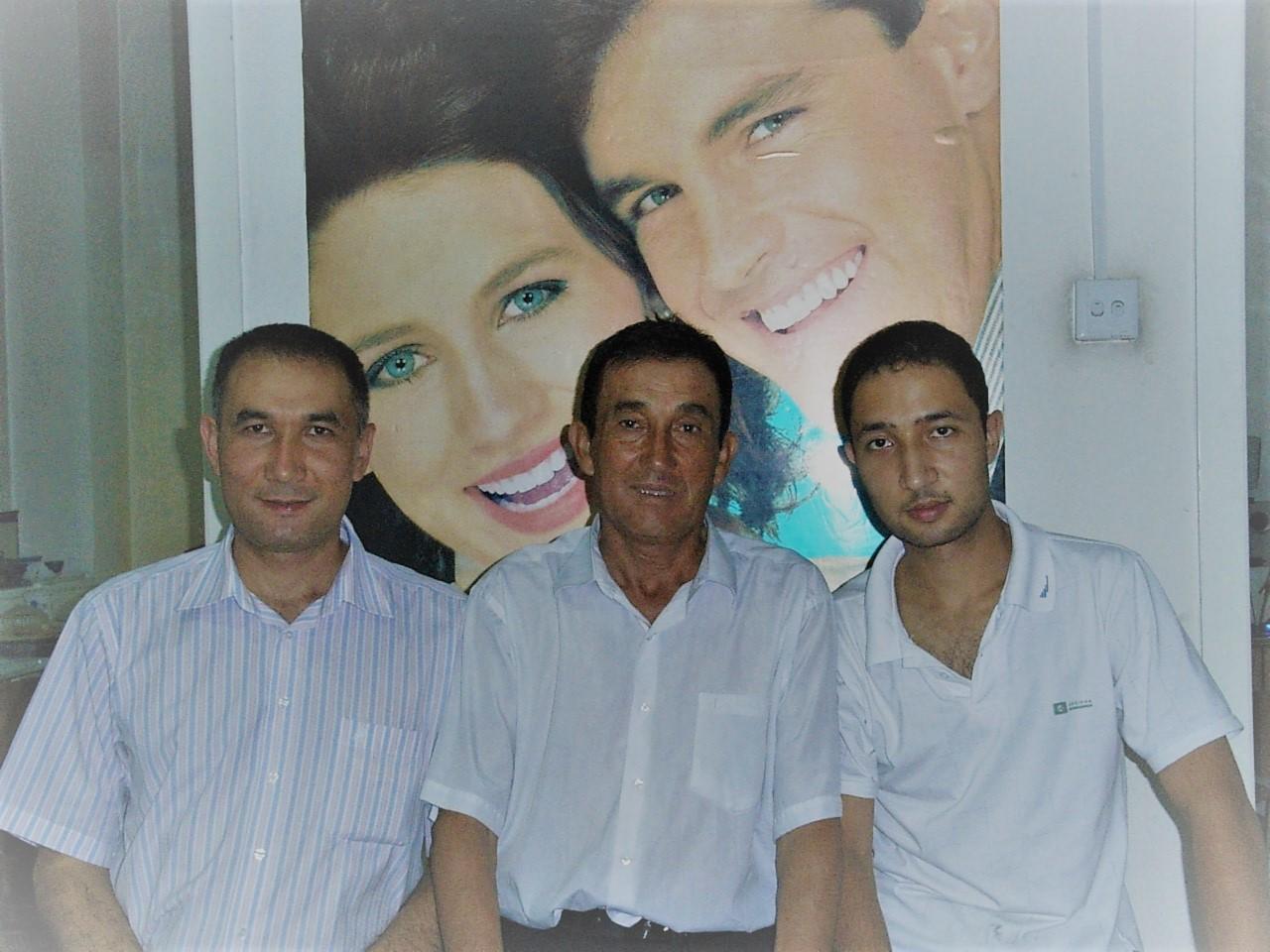

For five years, the brothers worked together, as Alim was training in Aziz’s dental clinic, the Heavenly Smile Dental Clinic, located in Ürümqi, nearby the Friendship Hospital. When Aziz won a Ford Foundation scholarship in 2009, he was due to start school in the United States on the 10th August. However, the 2009 Ürümqi violence erupted on July 5th.

The clashes started as peaceful protest against the authorities’ mishandling of a previous Shaoguan incident on the 25th June 2009, where allegations of rape at the Shaoguan Toy Factory instigated a mob attack which resulted in the death and injury of an unknown number of Uyghurs. While the authorities’ version of events admits two deaths and over one hundred injured, mostly Uyghur, a contemporary media report quoting an alleged participant indicated that the actual number of casualties might have been higher.

On July 5, a peaceful demonstration against the authorities’ mishandling of the event’s investigation was violently put down by the police, while simultaneously erupting into violence between Uyghurs and Han. The police used brutal force to suppress the clashes. Aziz claims to have witnessed the police shoot at the windows of Uyghurs who tried to film the scene. Aziz spoke with a Uyghur friend, a policeman, who alleged the police’s involvement in the organisation of the Han mob. His account agrees with the alleged footage of Chinese security forces giving arms to Han civilians referenced in a Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP) report.

News agency photos show large mobs of Han Chinese people marching through the streets, to serve a ‘justice’ they felt lacking in the already forceful security response. As James Millward writes, “Han demonstrators or mobs on 7 July seem to have moved about with impunity even as the press watched, in stark contrast to how the Uyghur demonstration on 5 July was repressed”. These ‘vigilantes’ were armed with a variety of weapons such as clubs, pipes, and cleavers. Uyghur shops and properties were destroyed, as police blockaded neighbourhoods and to an extent protected citizens.

Following the protest, Aziz witnessed Uyghur men being killed and his neighbours being arbitrarily arrested by Chinese police. Aziz, his wife, and his two children all lived on the sixth floor of an apartment block, where they hid through this period of extreme danger. A Han-Chinese mob formed, armed with batons, sticks, and shovels. They spoke of incidents of Uyghur violence against Chinese-Han. The mob threw Molotov cocktails at the building, while Aziz’s family were terrified in their apartment house. Uyghur people, determined to protect the neighbourhood, forced the mob to retreat.

Aziz’s family were ‘lucky’, but the precarity of their safety was clear. A video uploaded to Youtube in 2011, cited in this UHRP article as ‘in line with accounts’ from Amnesty International, appears to show unedited local media footage of the arrests in the aftermath of the protest, showing Uyghur men being dragged from their homes while hooded and stripped of their clothes, held at gunpoint and trampled on their heads. Aziz was concerned that he would be unable to leave for his scholarship as security started to tighten. A week after the riots, he left for Beijing, where he had to wait in hiding for three weeks before boarding the flight to America. International communications became blocked, and border security tightened, but just a year later Aziz’s wife and children were reunited with him in the States. They decided to stay in America for the best for the family.

Passports in Ürümqi come at a price, as the CCP have implemented policies of passport confiscation and recall for ethnic Uyghurs. A UHRP report, mostly based on interviews with expatriate Uyghurs, supports this conclusion, while media reports quote similar accounts by PRC citizens. According to these accounts, expatriate Uyghurs are told passport renewal can be a disingenuous offer to one-way travel to China as many who return go missing. Thus many refuse due to the danger of detention. Many Uyghurs, both at home and abroad, will turn to alternative methods for acquiring passports, which isn’t a viable option for some as it requires money and connections. Aziz states he paid more than one hundred thousand RMB (Chinese yuan) in bribes to government officials in order to arrange three passports for his wife and children to join him.

However, Alim was still in Shayar at that time. When Alim wanted to come to the United States, his visa was rejected by the US embassy. Aziz today still has copies of Alim’s passport and citizenship information, as he was trying to secure his younger brother’s entry into the United States. Now, Aziz uses these scans to campaign on his behalf through Twitter and news outlets.

In 2014, Alim was instead allowed to travel to Turkey, where he learnt Turkish for six months, but struggled finding work. When his family found him a job at the hospital in Shayar where his sisters worked (one as a lab technician, the other as a doctor), they asked Alim to return to Shayar.

Alim returned in early 2015, and, for a while, things were well. Alim no longer wanted to go to the United States, though he kept in contact with Aziz. Alim worked in the hospital for over a year. He met a nurse, and they became engaged, promptly moving in together. They were set to marry immediately after Ramadan, which in 2016 was between June 6th and July 5th. Unfortunately, this would never happen. Roughly two weeks before the wedding, in the last week of June 2016, Alim was taken. Aziz does not know the precise date of detention, nor does he know precisely why.

Aziz had been living in the States for several years, and used Skype to contact his family in Shayar regularly. In June 2016, when Aziz called his mother, Buaisam Muhtar, she seemed scared, largely remained silent, and refused to answer any questions. She abruptly ended the call. As Aziz learned of his brother’s imprisonment through his sisters, he continued trying to talk to his mother, who became increasingly speechless on their calls. Two months later, merely weeks before Xinjiang regional party secretary Chen Quanguo formally took power on August 16th, she told him never to call her again. That was the last time Aziz heard her voice.

Suddenly, Aziz couldn’t get through to any of his family in Xinjiang; his five sisters’ contacts disappeared from Aziz’s WeChat contact list, implying that they had removed his contact, but when he called the numbers they were out of service. Aziz tried to call the hospital, but anyone who picked up the phone denied it was a hospital; similarly, all the numbers that Aziz had of local police stations had mysteriously changed. They were either dead tones, they rang without answer, or the recipient would claim it was a private telephone line. From then on, Aziz could only hear what was happening to his family through what others tell him.

The story of Aziz and Alim shows also the extent to which the Xinjiang authorities monitor communication and information. Phones are monitored constantly through state-mandated apps, which sift through the phone’s data, ‘spy’ accounts used by the state to pose as dissidents, and regular checkpoints where all devices are examined.

The same goes for monitoring testimonies about missing family members. After one testimony, Aziz received a threatening direct message to his YouTube account. Although he did not keep the message, he remembers it communicated that he should stop publicising his family’s case if he wants them to be safe. Aziz sees this as a good sign: ‘It means the Chinese government is watching me’.

Aziz also frequently receives phone calls from unknown numbers, saying that the Chinese embassy in Washington D.C. has unsigned papers he must go back for, that they need his signature or that they soon become out of date. He chuckles at that. Since January 2019, these phone calls happen on average twice a week from three different “places”: the Chinese Consulate in Houston, TX, and New York, from various branches of DHL Express, and from the Bank of China. All of these phone calls come from hidden numbers, cite important documents that must be picked up, signed for, and verified with personal information such as home address. Aziz assumes that he may be disappeared if he goes to the Chinese Embassy.

Alim is not the only one of Aziz’s family to have disappeared. Aziz’s wife, Gulruy Asqar, also has family members who have been incarcerated: her brother, Husenjan Esqer, has been released after over a year of detention. Gulruy suspects that this wasdue to his linguistic work for the state itself, at the Xinjiang Ethnic Language Committee. Husenjan will likely remain under probation for six months, and given ‘state approved’ employment. Since the takeover in 1949, the CCP has a history of controlling and persecuting intellectuals, particularly minority elites. In recent years, Uyghur scholars and academics face huge risk. Gulruy Esqer has a nephew from another sibling, called Ekram Yarmuhemmed, still imprisoned.

Reports have shown how the detentions and disappearances in Xinjiang devastate not only the imprisoned and disappeared ones, but also their extended families and friends in Xinjiang who are often distressed and immobilized not only by the uncertainty of their close ones’ fate, but also by feelings of perceived guilt. Aziz tells me that he feels he is not a good brother. He says, ’maybe I didn’t do enough, I will try to go do more.”

As indicated by the findings of Gene Bunin, the founder and curator of the Xinjiang Victims Database, there seems to be a threshold of attention that forces the authorities in China to do or say something: whether that’s a simple phone call from the victim, an embarrassingly artificial proof-of-life video, or freeing the victim entirely. In May 2019, Bunin wrote an article which advocates applying public pressure, compiling forty cases where “media pressure [was] effectively followed by a reaction on the Xinjiang side”. The Chinese state directly intervened in some individual cases of disappeared individuals shortly after media attention was directed towards them. Bunin himself wrote that he was “stopping short of claiming causation but insisting that the correlation was, at the very least, extremely curious”.

There have been multiple cases in the past year of formal media replies from the CCP, and these seem to have been precipitated by the media campaigns brought about by their relatives. Iminjan Seydin, a famous publisher, was taken in May 2017 and sentenced to fifteen years in February 2019. His daughter gave testimony on Twitter, after which China Daily showed a video of Iminjan this May 2020 saying he was “living well, healthy, and free” (his shaved head indicates he was recently released). Nurmuhemmet Tohti was detained for four months before passing away from an alleged heart attack in May 2019. After international publicity, a PRC embassy in Canada told The Globe and Mail that Nurmuhemmet was not detained, merely under surveillance in a designated space. After continuing attention, the Global Times wrote their counter article March 2020.

Three Uyghur activists garnered similar attention after working with the U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who released a statement here. Gulnar Telet was eventually released after heavy campaigning from her Son, Arafat Erkin, who appeared in this NBC news video. Zumret Dawut sought refuge in the United States after facing detention and sterilisation, speaking out here. Minewer Tursun, the Mother of campaigner Furkat Jawdat, has been featured in The New York Times. Their high profile campaigning meant that the Global Times responded to all three activists by disparaging their claims in this article. This propaganda appears as a direct response to their campaign, and also acts as proof-of-life.

The CCP appears to follow some media coverage and has been occasionally seen to respond to international media focus. Aziz suggests that this article might save his brother, and as extraordinary as that might sound, it is not an unfounded statement.

Although Aziz has been campaigning, nothing has happened because his story has not reached enough attention yet. Aziz has tried to spread his brother’s story as much as possible, protesting and canvassing politicians. He also gives frequent testimonies on Twitter as well as Uyghur Pulse, a project which broadcasts video testimonies for the victims of Xinjiang human rights abuses. News outlets that Aziz contacted with his brother’s story responded that this type of case no longer constitutes news. One even added that were his brother a scholar, an artist, someone in the public eye, then maybe they would have a reason to print it.

Aziz’s traumatic escape from Xinjiang should entail a happy ending, living freely with his family today. However, his brother, Alim, is still in danger. As previously mentioned, there is a rumour he was transferred to Korla, but there is no state transparency regarding where he is currently detained. There’s a tragedy in Aziz’s ‘free’ years being spent in attempts to get international media to pay attention to this trauma, trying still to free his brother. As he writes on his Twitter under each post, ‘I will not stop giving testimony about Alim Sulayman until he is released’.

Thanks to Gene Bunin for comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Emily Upson is a part-time editor of the Xinjiang Victims Database. She is an independent researcher in anthropology, researching how international organisations financially and socially pursue peace.

The Xinjiang Victims Database is an open online repository that focuses on documenting the individuals impacted by the recent mass incarcerations in Xinjiang.

For a recent interview with Gene Bunin, the Database’s curator, see “Xinjiang crisis: Not a matter of politics, but of being human”.