Today is the thirtieth anniversary of the June 4 massacre in Beijing and I remember it like it was yesterday. I was staying at the house of the New Zealand Chinese poet Gu Cheng and his wife Xie Ye on Waiheke Island. When we turned on the Concert Programme at 8 am to catch the BBC World Service news, the sound of gunshots thundered out of the old radio. Tanks were rolling in to Beijing, quelling six weeks of peaceful protests in Tiananmen Square. The People’s Liberation Army had been turned against the people.

That night we met with others in the local Chinese community who wanted to show their solidarity with the people of China. At the house of one of my teachers we listened in tears to a broadcast of Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke as he spoke out against the CCP government’s brutal act. The New Zealand government also publicly condemned the massacre. TVNZ’s 6 pm bulletin relayed the grim face of the PRC ambassador as he walked in to meet the New Zealand foreign minister.

The Chinese Department at Auckland University cancelled all classes for a week to mourn the dead. Chinese students at Auckland University helped coordinate a protest march. Two days later more than six thousand New Zealanders and Chinese students studying in New Zealand, marched up Queen St. A busload of Chinese students travelled down to Wellington to lead a protest outside the PRC Embassy. At Taihape, one of the students was thrown off the bus as he was caught calling the embassy to inform them of our plans.

We’d all been closely following the protest movement since it began in April 1989. We watched it grow from a one-off student demonstration during the funeral of a senior CCP leader, to a tent city of thousands of rebellious youth at the political heart of China and mass protests of students and workers in every major city. The students were consciously upholding the tradition of revolutionary youth as the conscience of modern China.

The six week Beijing pro-democracy movement attracted strong international attention, not least because it coincided with the historic rapprochement between China and the Soviet Union in May 1989, marked by the visit to China of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Scores of foreign journalists came to report on Gorbachev’s visit, and stayed on to watch the drama unfolding in the streets of Beijing.

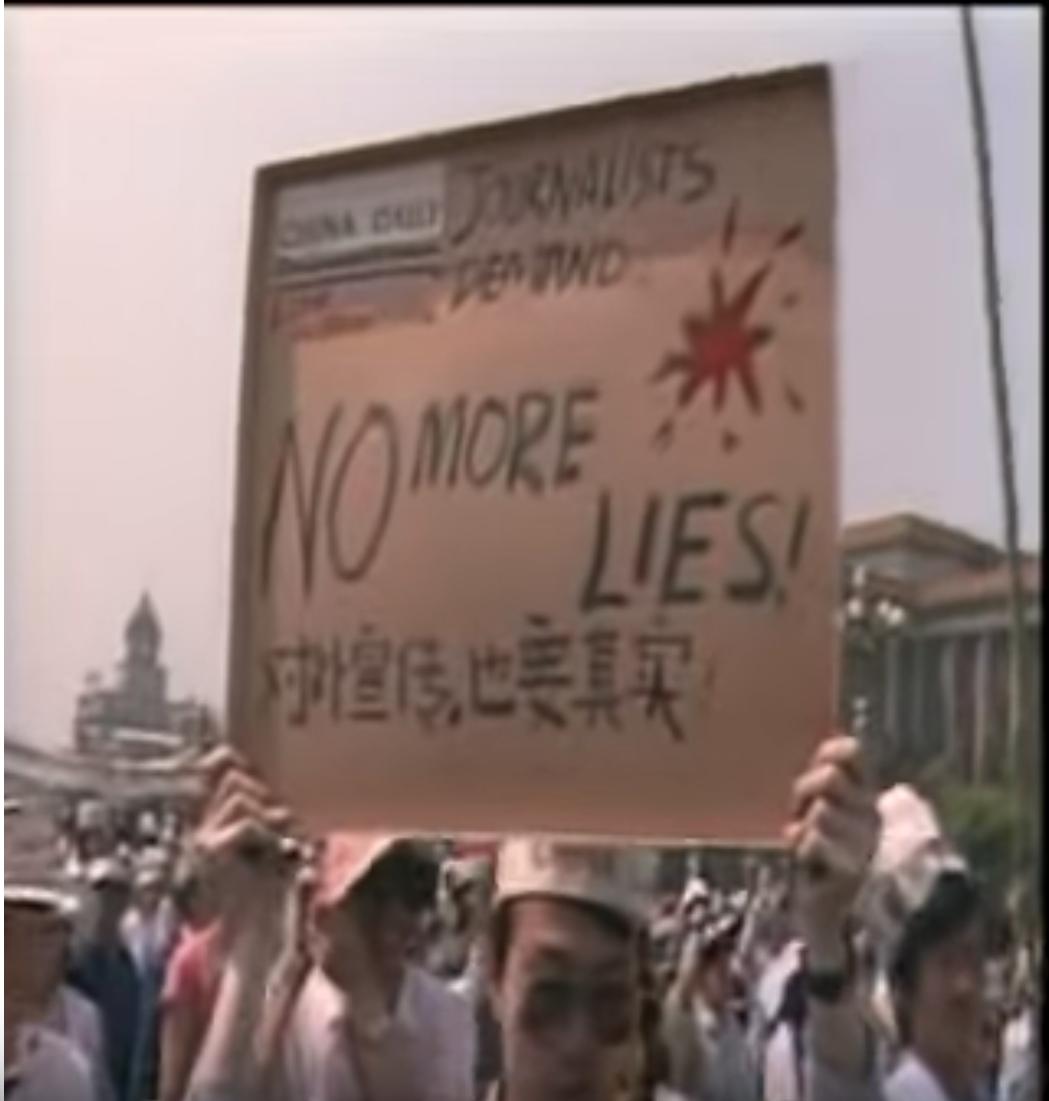

In the final weeks before the crackdown even Chinese journalists were marching in the streets. A China Daily reporter’s banner said it all: “Journalists Demand: No More Lies!” another proclaimed: “I ♥ Free Press”. Suddenly, in the first days of June, the Chinese media began to report truthfully and fairly on the events in the Square. For many Chinese people like my husband, then a young worker, it was like being able to breathe freely after years of suffocation. Students from the Central Academy of Art constructed a massive papier-mâché Goddess of Democracy, a fragile symbol of liberty and the temporality of this brief moment in Chinese history, the eye of the storm.

On the afternoon of June 3, 1989, PLA soldiers took over China Central Television studios and the editorial office of People’s Daily. That night the two CCTV news anchors Du Xian and Xue Fei wore black. After reading the announcement that the government was ordering the people of Beijing off the streets, Du concluded her report with: “Remember this black day!” The two journalists were banned for life from Chinese television for this small act of protest.

The foreign media reported live on the crackdown from the streets of Beijing, showing the world the sights and sounds of citizens being gunned down in cold blood. One image caught global attention, that of a lone Beijinger, shopping bags in hand, confronting a tank. For the Western world, “tank man” became a symbol of the courage of the individual facing down state violence.

No one knows exactly how many people died in the crackdown. The CCP government incinerated the bodies and ordered hospitals to purge any records. Estimates of the dead range from several hundred to more than 2,000, with many thousands more wounded and an estimated 10, 000 detained.

June 4 was a turning point in Chinese politics. The government set a line on the limits of political reform and showed the population what it was prepared to do to enforce that line. It caused lasting damage to the CCP’s international reputation. Negotiations on China’s entry into the WTO were suspended, China lost out on a bid to host the 2000 Olympics. Many governments cut high-level political contacts. The USA and European Union restricted exports to China of military technology and equipment, which remain in place to this day.

A new era of political control began after 1989, the CCP focused on maintaining the one party-state at the same time as engaging in state-led market reforms. The “post-1990 generation” youth of China were fed a diet of patriotic education.

In the thirty years that have followed, the public trace of June 4 has been deliberately and systematically erased in China; thrown down the memory hole. It is forbidden to mention it in public discourse and it does not exist in China’s history books. Yet every year, people in China are arrested for trying to commemorate it. The CCP’s efforts to control the narrative is not confined to China. The censorship controls imposed on the diaspora media under Xi Jinping means that few Overseas Chinese media outlets will now commemorate June 4 or report events associated with it, despite the fact that the anniversary has been headline news for three decades. This year, on May 31, Twitter closed down thousands of Chinese dissidents’ Twitter accounts. Twitter is banned in China, but many in China access Twitter via VPNs—which are also banned.

The Tiananmen massacre is like an open sore on the Chinese body politic. The CCP leadership understands this. In 1999, the government was contemplating reversing the verdict on Tiananmen, but instead they launched another crackdown, this time on the spiritual organization Falungong.

Despite the efforts of the CCP to suppress the discourse on June 4, the wound will only be healed when the government acknowledges what the writer Bing Xin said in 1989: the students were patriotic. But the CCP does not trust its own people and Xi is now ruling China in crisis mode. The human rights situation in China has gone backwards.

In 2019, as in 1989, the outside world has a crucial role to play in speaking up against human rights abuses in China. Today we should remember the sacrifice of the brave individuals who dared to confront the failings of their own government. And we should ensure that the Chinese diaspora in our own societies have freedom of speech and association, and that CCP censorship is not allowed to encroach in our media environment.

Anne-Marie Brady is Professor in Political Science and International Relations at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand, and a Global Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC. She is a specialist in the politics of the PRC and the CCP’s Party-State system; as well as polar issues, Pacific politics, and New Zealand foreign policy.

This piece first appeared on Newsroom. Sinopsis is publishing it, with the author’s permission, as part of a series on the 30th anniversary of the Tian’anmen massacre.