Albania is geopolitically important on the European periphery, forming a land bridge between Europe and Asia. Though rich in natural resources, it is one of the most underdeveloped states in South Eastern Europe. Albania is now a member of the 17+1 grouping, a China-centred strategic bloc located in Central and Eastern Europe. It has been touted as a potential link in European routes for China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative. In 2016 China’s ambassador to Albania characterized Sino-Albanian relations as a “traditional friendship bearing new fruits”. Is Albania repeating its history and leaning to one side?

United front work plays an important role in Xi Jinping’s “New Era” foreign policy. Like water on limestone, united front work will seek out the cracks and weak spots in each society. As each society has different fault lines, so the vectors of united front work may be different. Albania is an interesting case study for understanding how CCP united front work adapts, but also, how societies respond to it. Albania and China were famously close in the Mao and Hoxha years, until an ideological split in 1977 ruptured relations. Albania is geopolitically important on the European periphery, forming a land bridge between Europe and Asia. Though rich in natural resources, it is one of the most underdeveloped states in South Eastern Europe. Albania is now a member of the 17+1 grouping, a China-centred strategic bloc located in Central and Eastern Europe. It has been touted as a potential link in European routes for China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative. In 2016 China’s ambassador to Albania characterized Sino-Albanian relations as a “traditional friendship bearing new fruits”. Is Albania repeating its history and leaning to one side?

Introduction

Albania is one of the founding members of the 17+1 grouping, a China-centered strategic bloc set up in 2012 and located in Central and Eastern Europe. The group is also known as China-CEEC Cooperation (China-Central and Eastern European Countries). China-CEEC is part of China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Albania is touted as a potential link in European routes for BRI.

Albania’s economic and political relations with China have quickly gathered momentum since 2012. China and tiny Albania (current population 2.8 million) had a war of words after the 1977 ideological split between Hoxha’s Party of Labour of Albania (PLA) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Yet in 2016, the Chinese ambassador to Albania characterised relations between China and the Republic of Albania as a “traditional friendship bearing new fruits”. Is Albania repeating its history and leaning to one side? This paper examines contemporary Albania-China relations through the lens of united front work, assessing both China’s intentions and Albania’s response.

Under CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping, united front work has an important role in China’s increasingly assertive foreign policy, which follows a three-pronged approach:

1. State to State interactions.

2. Employment of military force.

3. Covert operations via international united front work activities.

The CCP’s international united front work is a form of political warfare and political interference, using “front” organisations and individuals. Domestic united front work is used as a tool of control over the Chinese people. Mao Zedong praised united front work as a “magic weapon” which helped bring the party to power.

After years of maintaining the fiction of a separation between Party and State, the CCP and its agencies now have a very prominent role in Xi foreign policy. United front work is the task of all party members and Party-State-Military agencies. Now that 70 percent of the CEOs of Chinese major companies are Party members, this means Chinese companies are required to take part in united front work. The CCP approach to foreign policy is called “total diplomacy”, meaning that every possible channel will be utilised.

Each society is somewhat different, so the emphases of united front work may be different in each country. Albania is an interesting case study for understanding how CCP united front work adapts, but also how countries respond to it. This paper gives an overview of CCP united front work efforts in Albania, using the categories set out in Anne-Marie Brady’s “Magic Weapons” template on CCP united front work:

- Efforts to control the Chinese diaspora, to utilize them as agents of Chinese foreign policy, and to suppress any hints of dissent.

- Efforts to coopt foreigners to support and promote the CCP’s foreign policy goals, and access strategic information and technical knowledge.

- Promotion of a global, multi-platform, pro-China strategic communication strategy aimed at suppressing critical perspectives on the CCP and its policies and advancing the CCP agenda.

- Extending the China-centred economic, transport and communications strategic bloc known as the Belt and Road Initiative.

In Albania, the main vectors of united front work appear to be China’s project to roll out the BRI economic, transport and communications strategic bloc, targeting Albanian economic and political elites, and attempts to shape a positive narrative about China in Albania. As Albania, like other China-CEEC states, has only a tiny resident Chinese population, the impact on Albanian politics of CCP efforts to control the Chinese diaspora has little observable impact on domestic politics. This is different from the situation of nations with large Chinese diaspora such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Singapore, where united front work targeted at the diaspora has had an observable impact on local politics.

Why China is interested in Albania

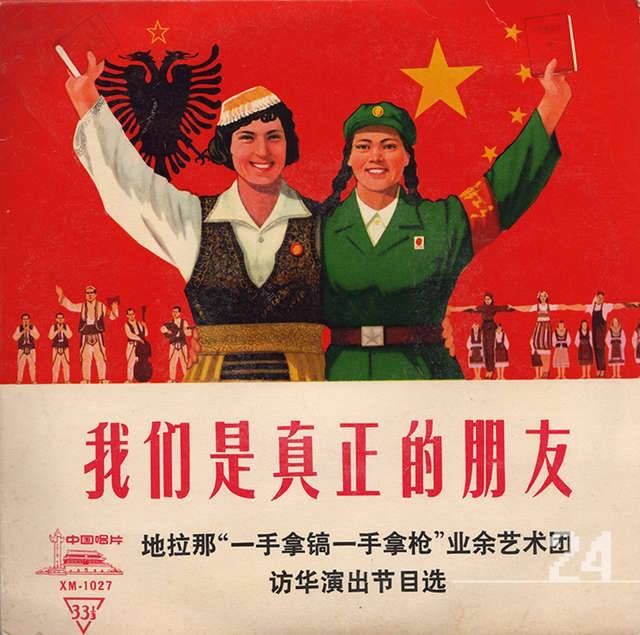

During the Cold War years, Albania became a symbol of the global power struggle between the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Albania was originally part of the Soviet-led Eastern Bloc. But in the 1960s, as the Sino-Soviet split deepened, Albania was at odds with the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia. Albania turned to China for protection and received many millions of dollars in economic aid and military equipment. China also sent an estimated 7000 Chinese advisers to Albania. By 1966, 70 percent of Albanian trade was with the PRC. Premier Zhou Enlai visited Albania three times, in 1964, 1965 and 1966, Albania’s senior leaders also visited China frequently in those years. The Party of Labour of Albania was the only ruling party in the world to support the Cultural Revolution. In 1967 the CCP praised the relationship between China and Albania as an “unbreakable militant friendship”.

Yet within ten years, the “unbreakable militant friendship” had splintered over ideological differences. By the late 1970s, Hoxha was openly critical of the CCP’s expanding relations with the United States (US) and other Western nations. The CCP government punished Albania by cutting economic and military assistance and withdrawing its experts. It was a repeat of what the Soviet Union did to the PRC in 1961 after their relationship had ruptured. The China-Albania militant friendship bolstered Hoxha’s draconian rule. However, by the end of the Cold War in Europe, Albania was one of the poorest and most isolated of the former Eastern Bloc states.

With all this negative history, it is remarkable that Albania and China now appear to be developing a strong political, economic, and strategic connection again. Relations took a long time to repair. In 1989, the PRC and Albania began a more pragmatic relationship, when the two countries signed an agreement on economic and technological cooperation. Albania’s interactions with China remained at a low ebb for years. But Albania’s NATO, EU, Taiwan, and Muslim connections, as well as the country’s strategic resources and geopolitical significance are among the reasons China restored its relations with Albania to a deeper level.

In 1990, the communist era came to a peaceful end in Albania, after a series of mass demonstrations. Democratic elections were held in 1991. Successive democratic Albanian governments have focused on integrating the Albanian economy with their European neighbours and seeking the shelter of membership in the North American Treaty Organisation (NATO). In 1992, Albania joined the North Atlantic Cooperation Council, and then in 1994, it entered NATO’s Partnership for Peace.

Albania also began to develop relations with the Republic of China (ROC, Taiwan). Parliamentarians established an Association of Friendship between Albania and Taiwan. In 1999, Taiwanese diplomats offered Albania US$1 billion in aid over ten years to switch recognition to the ROC from the PRC. At the same time, the Albanian government was also in talks to receive loans from the PRC. The pro-Taiwan parliamentary group was closed down in 1999, when the Albanian government’s policy on China changed. In a joint communiqué with the PRC in 2000, the Albanian government reiterated its support for the “One China” policy and stated that the “Republic of Albania will not establish official ties or conduct official contacts with Taiwan in any form”.

Albania is Europe’s only Muslim-majority nation and because of this, has had many connections to international efforts to combat Islamic terrorism, some of which link to China’s interests. Fifty-eight percent of the Albanian population are Muslim (mostly Sunni). In the early years after the end of the communist era, Muslim charities flocked to help rebuild Albania. Many of Albania’s new democratic leaders were Muslim. In 1994, Osama bin Laden established a base in Albania, via a Saudi charitable organization run by the Egyptian organization Islamic Jihad. Osama bin Laden used Albanian charitable activities to provide a rest and training area for fighters on their way to the conflicts in Bosnia and Kosovo, and to support a transit route for supplies and funding. In 1997, the CIA helped to reform and retrain the Albanian security agency SHIK (Shërbimi Informativ Kombëtar), after SHIK’s director and deputy director were forced to resign due to their links to radical Islam. In 1998, SHIK and the CIA conducted a joint operation against bin Laden’s group in Tirana, capturing four Egyptians and a substantial quantity of Albanian travel documents—100, 000 Albania travel documents had been stolen a few years before. Following these raids, according to the International Crisis Group, the Albanian government worked with US intelligence to detain and expel any Albanian-based foreigners suspected of using Albania as a hub for terrorist activities in Western Europe.

During the 1999 war in Kosovo, when more than half a million Kosovar Albanians were forced out of their homeland, the PRC sided with Yugoslavia and vehemently protested against NATO intervention in the conflict. The Albanian government allowed the US to use its territory and airspace to attack Serbia during the Kosovo war. In 2004 and 2005, the CIA used Albania as a transit point for “renditions” of suspected terrorists. Then in 2006, the Albanian government agreed to provide refuge to five Uighur men who had been wrongfully detained by the US government and held in Guantanamo prison for five years. The men had been captured by bounty-hunters on the Afghani-Pakistan border in 2001 and accused of terrorist activities. The US government allowed PRC Ministry of State Security officials to interrogate the Uighurs in Guantanamo. But all five of these men were cleared by the US of involvement in any terrorist activities. They were sent to Albania, as no other state would take them and they feared returning to China. The CCP government pressured the Albanian government to return the five men to China for trial—even though they’d been cleared of involvement in terrorist activities. Albania held firm however, and the five Uighur men remain in Albania today, still without papers, in limbo.

Albania’s participation in NATO and EU candidacy are frequently highlighted in Chinese government materials. In April 2009, Albania became a full member of NATO. In the same year, Albania joined the European Free Trade Association and applied to join the European Union. Since 2009, Albania’s NATO-member neighbours, Italy and Greece, have provided Albania’s air patrols. In 2019, Albania became the first country in the West Balkans to host a NATO air base.

It was also in April 2009, that during the visit to Beijing of Albanian Prime Minister Sali Berisha, China praised Albania as a “traditional cooperative partner” of China. According to a Chinese media report analysing how the CCP government refers to different states, this special terminology signifies that China hopes its present day relations with Albania will be a “model” to other small states. 2009 marked the 60th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between the PRC and Albania. During his 2009 visit, Prime Minister Berisha met with Premier Wen Jiabao and signed an agreement to take relations between the two countries to a new level, prioritising economic cooperation. But it wasn’t until 2012 that Sino-Albania relations really took off, as part of China’s more ambitious foreign policy under Xi Jinping. In 2012, Albania joined the 16+1 [now renamed 17+1] China-CEEC group, a China-centered strategic bloc of states in Central and Eastern Europe. In 2017, Albania also signed an agreement to participate in BRI.

During the Mao years, the CCP’s main interest in Albania was winning the ideological and strategic war against the Soviet Union. But in the Xi era, Albania’s main role in China-CEEC cooperation, and in BRI, is as a source of strategic natural resources for China. Albania is rich in chromium, copper, nickel and crude oil. Albania’s location also has geopolitical value to China. Albania forms a land bridge into Europe from central Asia. Albania could be a useful hub for enhanced China-Europe transport and communication links. It is the shortest overland route between the Adriatic and the Aegean seas. Albania is also geopolitically important to both the US and Russia, which is another reason for China’s interest.

If we look at China’s foreign policy in the CEEC zone and central Asia, the CCP appears to be in the process of creating a buffer zone, the outcome of which could be to weaken Russian influence in Central Asia, as well as Northern, Central and Eastern Europe. Eleven of the current members of CEEC were formerly communist states and allies of the Soviet Union. China dominates the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, which links Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan, and Russia, plus observer state, Mongolia. China has an unresolved territorial dispute with Russia and some competing foreign policy agendas. But for now, China needs to be in close partnership with Russia to counter-balance the US.

Albania and the Belt and Road Initiative

In 2014 the Xi government launched the Belt and Road Initiative, a new global political, economic and strategic bloc. PLA spokesperson Peng Guangqian says that the BRI aims to reshape the global order. BRI builds on the Jiang era “going out” (走出去) policy, which aimed to stimulate the Chinese economy by acquiring privileged access to global natural resources and gaining contracts for international infrastructure projects.

BRI has expanded beyond the “going out” strategy to create a China-centered network of roads, railways, and ports, as well as a “Digital Silk Road” which will connect China’s BRI partners to China’s own information communication systems such as Huawei and the Beidou GNSS. If China can persuade BRI partner states to host Beidou ground stations and incorporate Beidou navigation systems into local mobile phone networks it will greatly enhance China’s military capabilities. Global navigation systems are a critical enabler for military operations. They provide missile positioning and timing, access to fleet-based broadband for unclassified and classified systems, and they enable environmental situational awareness. The US invented GPS (global positioning system) for military operations, and the whole world now depends on it. But by 2020, the US may have lost its technological advantage in GPS over strategic rivals Russia and China, who are developing their own rival global navigation systems, GLONASS and Beidou.

At the Central Economic Work Conference in December 2013, the Chinese government categorised the agenda for BRI into “six tasks” and “five connections”. The six tasks of BRI are:

1. Using economic ties with foreign countries to support China’s food security.

2. Supporting Chinese industry to engage in economic stimulation activities.

3. Preventing a debt crisis in China by balancing regional development in China.

4. Improving the standard of living in China.

5. Expanding China’s external transport routes.

6. Reducing the impact of chokepoints such as the Malacca Straits.

The “five connections” are:

1. Policy coordination.

2. Transportation links.

3. Trade links.

4. Currency swaps.

5. Information and communication technology links.

Anne-Marie Brady’s “Magic Weapons” template assessed BRI’s role in Xi-era united front work via six stratagems:

1. Using external projects and the exploration of overseas strategic natural resources to stimulate China’s economic development.

2. Creating trade zones, transport infrastructure, and communication platforms between China and other countries.

3. Exporting the “China-model” to foreigners via exchange and training programmes.

4. Reinforcing party-to-party links with foreign national governments as well as their local governments.

5. Utilising Sino and foreign think tanks to shape foreign public opinion on BRI and Chinese foreign policy overall.

6. Utilising united front work, management of the Overseas Chinese community, and news media management activities to promote BRI and Chinese foreign policy goals.

A 2019 Sinopsis paper by BRI expert Nadège Rolland confirms these six stratagems, adding in useful detail on BRI united front work organisations to look out for such as the Silk Road Think Tank Network, China Council for the Promotion of International Trade, and the Silk Road Chamber of International Commerce. All of these have been active in Albania.

Albania signed an MOU with China on BRI in April 2017. But it was already linked to BRI through China-CEEC, which was merged into BRI in 2016. Albania was one of the founding members of the China-CEEC politico-economic bloc that aligns China with seventeen European countries: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, and Slovenia. China-CEEC was set up in 2012. Until Greece joined in 2019 the grouping was known as “16+1”. In Chinese language materials China-CEEC cooperation is referred to as a regional sub-set of China’s BRI strategy.

China-CEEC has been given high-level support by China’s most senior leaders. The China-CEEC Secretariat was established in September 2012, demonstrating that China-CEEC is meant to be a long-term strategic political and socio-economic bloc. The terms of agreement between China and CEEC have steadily expanded. In 2015 China and the CEEC states agreed that between 2015 and 2020 they would focus on cooperation in the areas of economy, transport infrastructure, heavy industry, finances, agriculture, technology innovation, cultural communication, health and city diplomacy. The 2016 China-CEEC meeting in Riga emphasised transport and infrastructure and announced that the 16+1 initiative would merge with BRI.

As noted, Albania’s core role within the BRI strategy is as a source of strategic natural resources for China. Mineral products and metals made up 31 percent of Albania’s exports in 2016, including chromium, copper, nickel and crude oil. In March 2016, a Canadian company, Banker’s Petroleum, sold its Albanian oil exploration and production rights to Geo-Jade Petroleum (洲際油氣股份有限公司), a Chinese company whose main businesses are located in Kazakhstan. Bankers Petroleum was forced to sell its Albanian investments after the Albanian government accused it of money laundering, tax fraud, and polluting the environment. Geo-Jade has full rights to develop the Patos-Marinza oilfield, Europe’s largest onshore oil reserve, and a 100 percent interest in the Kucova oilfield, Albania’s second largest oilfield. Beijing-based mining and metals company Sinomine Resource Exploration also has a subsidiary in Albania to conduct mining site construction and it is doing surveying with a local geological institute. In addition to the mineral sector, China is also investing in Albania’s agricultural sector.

Another potential role for Albania within BRI is as a transport hub. Albania is a land bridge between Europe and Central Asia. In November 2015, Albania, Montenegro, and the company Pacific Chinese signed a trilateral Memorandum of Understanding on plans to construct the Adriatic – Ionian Highway. This future coastal highway will run from Trieste to Kalamata, and will link Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Albania and Greece. The highway could help Albania become a hub for maritime transport. However, the project has been fraught with controversy over allegations of money-laundering and corruption. Albania already has a sordid history of ambitious road projects that were not properly completed, with funds embezzled. Following massive student protests in late 2018, the Albanian government cancelled plans for development of the Thumanë–Kashar section of the highway in 2019, saying it was now going to channel the funds set aside for it into education.

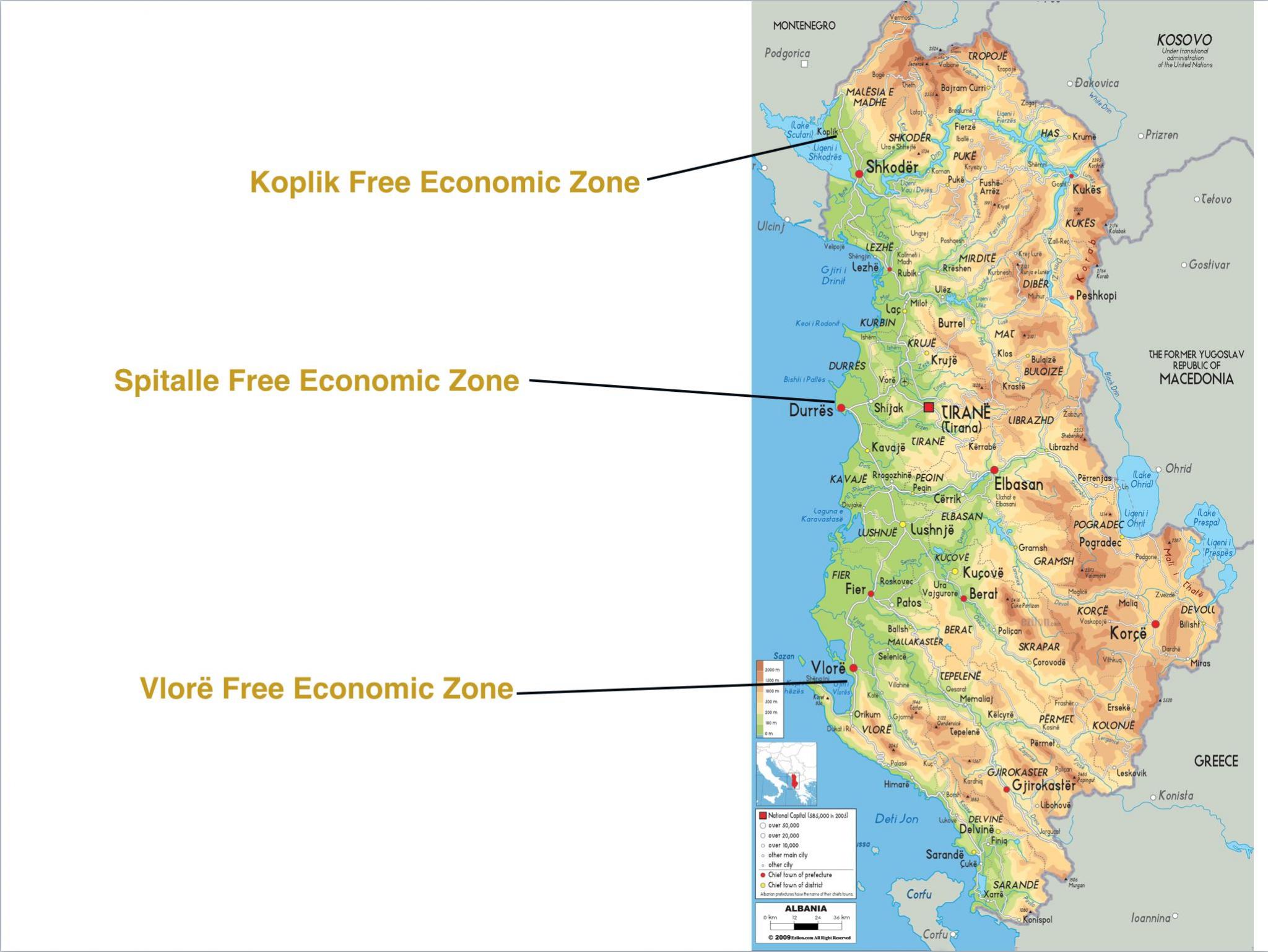

The BRI strategic documents recommend setting up trade zones. In 2015 Albania announced plans to establish three economic and technological development zones: Spitalla Free Economic Zone; Koplik Free Economic Zone and Vlorë Free Economic Zone. In April 2017, China’s deputy Premier, Zhang Gaoli, visited Albania. Zhang said that China would expand its investment in Albania and specifically mentioned investment in Albania’s free trade zones, as well as transport infrastructure and energy projects. Macedonia and Turkey are supportive of Albania’s Koplik Free Trade Zone because of its closeness to their own economies. The zone is 45km away from the Port of Shengjin in Albania, 34 km from Bar port in Montenegro, and 127 km from the port of Durres. Skeptics say Albania has previously promoted multiple free trade zones, which have received little interest from foreign investors, deterred by problems relating to land ownership in Albania, the lack of infrastructure and problems as basic as reliable electricity, ongoing political instability and endemic corruption.

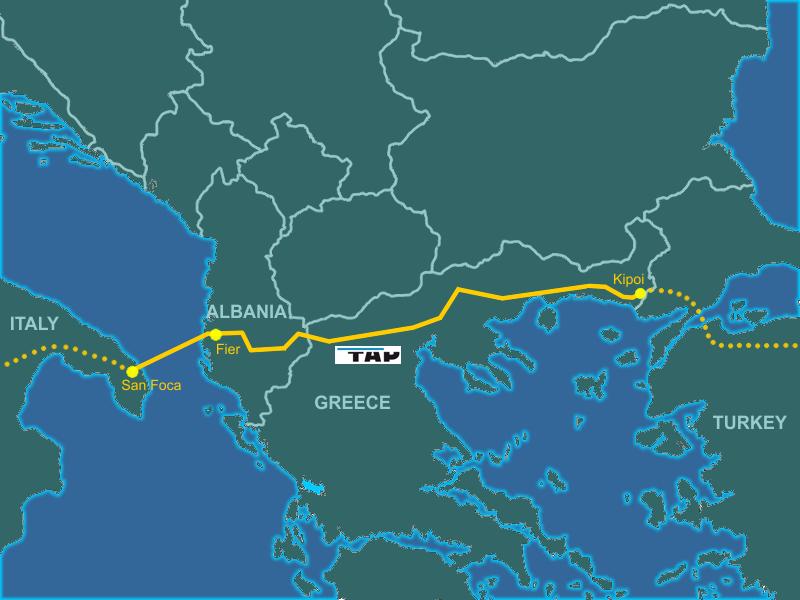

Despite this setback, other infrastructure projects continue. In 2016 China’s Everbright Group bought Tirana’s Nënë Tereza International Airport Company and it has a concession on the airport until 2027. The aim is to set up a logistics centre to transport Chinese goods into Europe and to promote tourism in Albania, especially tourists from China. Albania is also a crucial link in the Trans Adriatic Pipeline which connects the oilfields of Shanghai Cooperation member Azerbaijan with the markets of Europe.

Albania is also connected to China’s Digital Silk Road. China’s global navigation system, Beidou, is now in use in Albanian mobile networks. China’s controversial telecom company Huawei has an Albanian-registered company, Huawei Technologies Albania SH.P.K. Huawei contributes to Albania’s 4G network and Huawei phones are common in Albania. However the Albanian government has not yet made a statement on the vexed question of Huawei and 5G and there are no signs yet of a Beidou ground station on Albanian soil.

China’s efforts to influence Albanian political and economic elites

The goal of CCP united front work towards foreign and economic elites is 1. to get them to promote China’s foreign policy agenda within their own political systems, 2. to use them as a source for information on their government’s intentions and attitude towards China and its policies, and 3. to provide China access to new technology and military information. This last goal could be achieved with or without the consent of targets through compromising foreign VIP visitors’ electronic devices when they attend events in China.

CCP united front efforts in Albania follow a predictable pattern: a focus on political parties, local government, the business sector, youth, and intellectuals. Because a generation of Albanian elites had many interactions with China in the Mao-Hoxha years, CCP united front efforts can draw on a pool of older generation Albanian “friends of China” to help push forward cooperation. However, none of them are currently in a position to influence contemporary political decisions. The post-1991 elite received their training in Albania or the West and regardless of their politics, tend to be more at home in Europe or the USA than Xi’s parallel universe.

The core agencies used in CCP international united front work targeted at foreigners are as follows: the CCP International Liaison Department; the Communist Youth League, China’s “eight democratic parties”; the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries; Hanban and the Confucius Institutes; the Chinese People’s Institute for Foreign Affairs, China Institute of Contemporary International Relations as well as many other new Chinese government “think tanks”; the State Administration for Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television—which since 2018 has been under the direct control of the CCP Propaganda Department. the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; Ministry of Education; Ministry of Culture; PRC provincial and local governments; State Owned Enterprises and major Chinese corporations such as Huawei. All of these have been active in 17+1 BRI activities and in Albania.

The CCP is now trying to foster a new generation of Albanian “Friends of China” with offers of generous scholarships and trips to China. Chinese ambassador Jiang Yu describes Albanian students learning Chinese as “missionaries for China-Albanian friendship”. Albania has one Confucius Institute at the University of Tirana which is partnered with Beijing Foreign Studies University. It opened in May 2013 and Confucius classrooms were set up in several high schools in Tirana in the same year. The PRC Tirana embassy has gifted teaching materials to assist with Chinese language classes. The Albanian PRC embassy and Huawei’s Albanian subsidiary have partnered to sponsor Chinese culture competitions. Huawei also sponsors the ‘One Thousand Dreams’ programme in CEEC states including Albania. This programme will train 1000 IT talents for Huawei, donate 1000 books to university libraries, and give 1000 toys to children’s hospitals in each of the chosen countries. Twenty-nine Albanian government officials and scholars have been sent to China on short-term trips to study China’s agricultural techniques. In 2016, the Chinese embassy in Albania hosted the Sino-Albanian College Students Belt and Road Friendship Activity. Chinese companies Hong Kong Ta Kung Wen Wei Media Group (香港大公文汇传媒集团) and China Everbright Limited (光大海外基礎設施基金) sponsored the event. In 2017, the Tirana Confucius Institute was featured on a Digitalb Top Channel talk show and Albanian teachers and students shared their experiences of studying in China. At the 2019 China-CEEC meeting in Dubrovnik, the Albanian government agreed to host a China-CEEC Youth Development Center.

Friendship is a political term in CCP united front work, as it was also for the Soviet Union. The PRC embassy supports the Sino-Albanian Youth Friendship Association, the Albania-China Cultural Association, the Albania-China Friendship Association and the Albania-China Parliamentary Group of Friendship. The Albania China Friendship Association was re-established in 1991. An earlier group set up in the Mao-Hoxha years closed down after the ideological split between the two countries. The Albania-China Friendship Association promotes Albania’s participation in BRI and works closely with the Tirana PRC embassy. Many of its founding members studied in China in the 1960s and 1970s. In 2017 the head of the Albanian-China Friendship Association, Iljaz Spahiu was awarded the CCP Central Propaganda Department-funded Special Book Award of China. This prize is given to foreign scholars, translators, writers and publishers who have introduced Chinese culture to the world. Cultural links are a traditional channel for united front work. The PRC’s Chinese Disabled People’s Art Troupe, Beijing Song and Dance Troupe, the Nanjing Folk Orchestra, and a Chinese martial arts group have all toured Albania in recent years and Chinese art exhibitions have also visited.

Party-to-party links are an important channel for CCP united front work. The CCP utilises senior current and former politicians as bridges to their governments, and in exchange, offers them status, free trips to China and BRI events, and access to the CCP leadership for business opportunities. The Albania-China Parliamentary Group of Friendship is led by Vasilika Hysi, deputy speaker of the Parliament and senior MP in the Socialist Party-led government. The center-left Socialist Party was formed out of the renamed Communist Party of Labour of Albania in 1991. The Socialist Party of Albania, and the two opposition parties, the Democratic Party of Albania and the Socialist Movement for Integration have all participated in the CCP’s “China-Europe High-level Political Parties Forum” inter-party meetings from 2010 to 2016 as well as China-CEEC Young Leaders Forums. Luan Rama, Vice Chair of the Socialist Movement for Integration, participated in the 2017 “CCP in Dialogue with World Political Parties High-Level Meeting”, which launched the CCP’s direct participation role in Chinese foreign policy. Former Albanian president Rexep Meidhani has participated in China-CEEC public diplomacy events and is a vocal supporter of Albania’s participation in the BRI. In 2018, a delegation from the CCP International Liaison Department visited Albania and met with leaders of Albania’s three main political parties, who are bitterly divided over allegations of vote rigging in the 2017 election. Xinhua claimed that the Albanian politicians were “willing to learn” from the CCP’s experience in “governing the Party and governing the State”.

Another well-established CCP united front work approach is to create economic dependencies in susceptible economies via preferential terms of trade, loans, or directed mass tourism. As of 2019, China is Albania’s third largest export market, and third largest import source. However, Italy is still overwhelmingly Albania’s biggest export market with 72 percent share compared to China’s mere 3.5 percent, while Italy is also Albania’s biggest source of imports with 31 percent share compared to China’s 6.7 percent. Chinese companies have made significant investments in the mining sector. In 2018, CGTN the PRC’s foreign language television network, claimed that, “China is the single largest investor in the Albanian economy.” Yet according to Albanian government statistics, the Netherlands is actually Albania’s largest investor, while China still only ranks ninth.

One of the most common criticisms of China’s BRI is it is resulting in states becoming indebted to China at unsustainable levels. But Albania has taken up a relatively small amount of loans from China in the current period, and despite a lot of publicity about potential funding of projects, very little of them have come to fruition. Albania has a very high level of public debt, 68.8 percent of GDP in 2019. But Albania’s public debt is mostly held with the IMF, World Bank, German Development Bank, and EU, though China has loaned money to Albania in the past.

In December 2000, on the same day that Albania signed a communiqué renouncing all diplomatic contact with Taiwan, China announced it was loaning Albania US$100 million to finance the construction of the Bushat Hydropower Station. The station was built by China International Water and Electricity Corp between 2001 and 2008. The loan ballooned to US$150 million and was to be paid off over 12 years at 3.5 percent interest, adding more than US$60 million to the cost. In 2013 the Albanian government announced it was in negotiation with China Communications Construction Company to develop Shëngjin port at a cost of 2.2 billion euros. But the port development plans did not progress. In 2014 China’s Exim Bank offered Albania 250 million euro to build the Arbër highway in northern Albania, and offered another large block of funding for roading and irrigation projects. The Arbër highway contract was given to China State Construction Engineering Corporation (CSCE), with a plan to use Chinese labour, despite high unemployment in Albania. But in 2016 the Albanian media reported that Chinese diplomats were conducting an investigation into the project, due to corruption allegations. In 2017, CSCE withdrew from the contract, and the contract was taken over by an Albanian firm, Gjoka Construction. The road is now being financed through a public-private financing scheme between Gjoka and the Albanian state. In 2017, China granted a relatively modest 10 million yuan (1.5 million Euro) to the Albanian government to modernize the agricultural sector. The Bank of China is one of the funders of the 3.2 billion euro Trans Adriatic pipeline which will cross Albania. Most of the Adriatic-Ionian Highway will be debt financed by China’s Exim Bank. However, the Albanian Thumanë–Kashar section of the highway which was to be financed by the EU, through the Berlin Initiative, has not gone ahead. So despite all the big talk about BRI infrastructure projects Albania could be involved in, according to an assessment in the 2019 Munich Security Report, Albania is the only West Balkan state not receiving any loans from the BRI project.

The CCP government is trying to encourage more Chinese tourists to visit Albania. Albania has a lot of potential as a tourism destination: kilometers of unspoiled beaches and remarkable Roman-era historical ruins. In 2016, the Albanian Foreign Minister, Ditmir Bushati, signed a Memorandum of Understanding to simplify visa application procedures for citizens of Albania and China. As of 2018, Chinese citizens no longer need a visa to visit Albania. But Chinese tourism numbers have been slow to expand, due to fears about Albania’s poor public security. The China-CEEC Tourism Association meeting will be held in Albania in October 2019.

Under the policy of “using the local to surround the center” the CCP uses sister city links and local government investment schemes to influence central governments and promote China’s agenda. There is some evidence of this in Albania. China has included Albania in its city diplomacy efforts, sponsoring its participation in global city diplomacy events. As it does with opening up poor areas in China such as Xinjiang, China is planning to “twin” Tianjin with Tirana to ease the economy of scale for trade and other development between the two countries.

Foreign academics are a common target of CCP united front work. China offers them trips, paid talks, research funding, honors and distinctions. Several Albanian scholars have participated in the CCP’s High-level Symposium of Think Tanks of China and CEECs. In 2015, China’s General Administration of Press and Publication agreed to subsidise the translation into Chinese of fifty Albanian books. The first book to be translated is Mother Albania by the famous Albanian socialist and novelist, Dritëro Agolli. Mother Albania emphasises collectivism and solidarity, and praises revolutionary spirit. It is a reminder of the close ties between Chinese and Albanian communist history. The Translation Project of Classic Sino-Albanian Books aims to present positive images of China and Albania, and to shape positive public opinion. In 2016, the Tirana International Books Exhibition was held in the Albanian Parliament Building. The Association of Albania Publishers, the Tirana Confucius Institute, the Chinese Embassy and China’s Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press (外研社) of Beijing University participated in the exhibition to promote Sino-Albanian publications.

In 2018 academics from the Albanian Academy of Social Sciences joined in an “Albaniology” conference hosted by Beijing International Studies University’s Department of Albanian Language. China’s sole Albanian Language Department was set up in 1961, then closed down after 1980. In 1987 it was revived, but until recently it has been a very small programme. In 2017 Beijing International Studies University announced a major investment in subsidised Albanian-language studies (along with other CEEC) languages) to train diplomats and other professionals with the right language skills to further China’s 17+1 BRI strategy. Over a seven-year period, 20 undergraduates per year will be trained in Albanian, 20 in Bulgarian, 20 in Slovenian, 20 in Czech (Slovak), and 20 in Hungarian.

China’s global strategic communication strategy and Albania

Since 2009 the CCP has invested in a major project to control international perceptions about China and the policies of the CCP. Albania has a small media market so many of the CCP’s united front media-management efforts are via China-CEEC joint activities. The CCP’s key message directed at Albania emphasises economic links and aims to create a positive picture of Sino-Albanian relations that will help erase the negative memories of the past.

Radio Peking broadcast in Albanian during the 16 years of Sino-Albanian militant friendship, but this ended after the rupture in relations. The first tendrils of Sino-Albanian media cooperation resumed in 2012, when China Radio International and Albania’s Radio Televizioni Shqiptar signed a Programme Cooperation Memorandum, to exchange economic-related programmes between the two countries. The stated goal of this collaboration is to encourage more Sino-Albanian economic links and to create positive public opinion for the further expansion of Sino-Albanian relations. In 2013, China Radio International set up an Albanian-language FM channel in Tirana.

One of the core objectives of the CCP’s media management strategy is to get the international media to promote China’s political language and talking points. In 2017 CEOs of eleven Albania media organisations were invited to a “media friendship” meeting at the PRC embassy in Tirana. As they do in other states, PRC diplomats in Albania publish op eds in the local media promoting China’s foreign policy perspective.

In 2015, the Zhonghua Book Company and the Onufri Publishing House co-published “Xi Jinping Classical Quotations and Interpretation (习近平经典引句解读)” into Albanian language. The CCP Central Propaganda Department sponsors this major project to translate Xi Jinping Thought into world languages.

CCP policies towards the Chinese diaspora in Albania

According to official statistics, there are only 200 ethnic Chinese permanent residents in Albania. However, these figures do not take into account Chinese passport-holders in Albania on other visas. Chinese companies in Albania use Chinese labourers for construction projects and mining. There are also Chinese petty traders, students, and others residing in Albania on temporary visas. The CEEC region has a significant illegal migrant population from China (as well as from other states). Albania, Croatia, and Montenegro are the three main CEEC hubs for illegal Chinese migration.

The Tirana PRC Embassy keeps close ties with the resident Chinese community via cultural events such as the annual Lunar New Year Reception and associated community events. Senior Albanian political figures also commonly attend these celebrations. Unlike countries with a large Chinese diaspora, Albania does not appear to have its own Peaceful Reunification Association (the CCP’s main proxy organisation working with diaspora communities), nor is there yet any trace of a Chinese Student and Scholars Association (the CCP proxy organisation which is used to manage PRC students abroad) in Albania. Instead, CCP united front work organisations are connecting to the Albanian Chinese migrant community via free Chinese medicine clinics and Chinese food days, which draw migrants in for non-political purposes. The first such event in Albania was held in April 2019, with a likelihood of more to follow.

Assessing the Impact of Xi-era united front work in Albania

Xi-era CCP united front work in Albania follows a formulaic and predictable approach: the global promotion of BRI, efforts to access strategic natural resources and economic stimulus projects for Chinese companies; the quest to seek transportation link alternatives for Chinese exports; and expansion of the Beidou global navigation system. The CCP has tried to co-opt the Albanian elite to support and promote China’s foreign policy goals. China’s global strategic communication in Albania aims to suppress critical perspectives on the CCP and its policies, and also to advance the CCP agenda in Albania. The CCP uses united front work in Albania to manage relations with the Chinese diaspora. But what is in all this for Albania? And what impact, if any, is CCP united front work having on Albanian domestic politics and foreign policy, especially Albania-China relations?

Albania is the fourth poorest country in Europe and needs economic assistance and new markets. The IMF assesses Albania as an “upper-middle income country”. There is a big gap in the standard of living between urban and rural areas. Albania faces a demographic crisis, some 1.4 million people have left the country since end of the communist era and a further 52 percent are contemplating leaving. Official unemployment is at 13.7 percent. Growth is at 3.5 percent, down from 4 percent, due to the slowdown in the economies of Albania’s main economic partners. Successive Albanian governments have welcomed the CCP’s new initiatives and activities since 2012, because China is a potential source of financial aid, soft loans, investments, and has a massive market. China’s BRI loans are generally much easier to obtain than EU ones, which have strict lending criteria.

Nevertheless, if we cut through the rhetoric and look into the detail, Albania’s participation in China’s signature BRI infrastructure projects is surprisingly small. Albania has a modest amount of trade with China. Albania has taken up few loans from China and none via BRI. China ranks only ninth among Albania’s top FDI partners. Despite the CCP’s efforts to influence Albanian elites through united front work, Albania and China remain far apart on important political issues. While the Albanian government recognises the “One China” principle and keeps its relations with Taiwan (ROC) to a minimum, the PRC refuses to recognise the Republic of Kosovo and maintains close relations with Serbia. In 2018, China supported Serbia in excluding Kosovo from Interpol. Membership in Interpol would help Kosovo fight organised crime, a major problem for both Kosovo and Albania.

Yet China’s renewed relations with Albania have raised many concerns in the US and EU. Due to its strategic location on the Strait of Otranto, the political alignment of Albania has always been important to neighbouring states and great powers who wish to dominate in Europe. Albania has a long history of colonisation and being used as a pawn by foreign powers. From the days of Alexander the Great, to six hundred years of Ottoman rule, and the failed covert operations of US and UK-supported agents against the Hoxha government in the late 1940s, Albania has a long of experience of foreign political interference.

Xi-era China-Albania relations have revived some elements of the Cold War relationship, including bombastic political rhetoric and deepening economic links. But unlike during the Hoxha era, Albania now has a range of political and economic partners. China is a useful counterbalance to other political relationships and an important investment source. But China is no longer Albania’s only strategic partner.

Both Albania and China learned the hard lesson of the failure of the policies of the Hoxha and Mao years. For Albania, the big lesson was that neither autarky, nor developing a relationship with one great power, was the solution to its security. For China, one of the core lessons was that ideological unity should not be the main determinant of positive bilateral relations. In 2014, a former PRC ambassador to Albania wrote, “it is very necessary to downplay the influence of ideological factors on relations between countries. Only by temporarily shelving disputes in the ideological field, seeking common ground while putting aside differences, and by seeking common development with a peaceful and rational attitude can we win more room for [China’s] development on the international stage”.

Recent history tends to lead many Albanians to take a somewhat ironic, and even cynical, view of the CCP government. The negative history of the Mao-Hoxha years perhaps makes Albanians more resilient than most societies against being influenced by CCP united front work. In Albania, the Chinese diaspora is tiny and it is does not appear to be a vector for CCP political influence on the Albanian government. Albania has signed an agreement on BRI, but it has taken a cautious approach and has been careful not to take any actions that might harm its relationship with NATO. Albania is strongly committed to NATO and is a staunch ally of the United States.

The Albanian government is attracted to China’s investments and markets; but it is even more attracted to meeting the criteria to obtain EU membership. Albanian Prime Minister Rama has said that for Albania, joining the EU was about “finally having the possibility to place ourselves in a safe zone from the curse of history”. Rama has repeatedly urged the EU and US not to neglect Albania and “leave a space for other countries to fill”. He has emphasised that “other actors” in Albania “may not be very keen to see the European Union progress and prosper.”

Rama made his concerns even more explicit in a 2019 interview, stating that Russia, China, or Islamist radicals will fill the vacuum if the EU does not commit to Albania. Turkey and UAE are also influential players in Albania. In 2019, Albanian Minister of Defence, Olta Xhacka, said at a meeting with former US Defense Secretary Jim Mattis, that Albania wanted to host a US or NATO presence to counter Russian efforts to expand its influence, as well as to balance China and Iran’s growing interests in the region. Minister Xhacka told Mattis, “I believe that a very strong message needs to be sent, that the Western Balkans is a Western-oriented region”.

Prime Minister Rama’s political foe, President Ilir Meta, has been accused of working for Russian interests. In turn, in 2018 President Meta accused the then US Ambassador to Albania, Chinese-speaking Donald Lu, of interfering in Albanian politics through his probing into the investigations as to why Canadian Bankers Petroleum was forced to sell its business interests to China’s Geo-Jade Petroleum. Interestingly, Albania’s current Trump-administration US ambassador is also a Chinese-language speaker. Some Albanians have accused the EU and US of interference in Albanian politics, “paving the path for an explicit subordination of Albania to US interests”. In 2016 a temporary change was made to the Albanian Constitution, as a precondition for Albania’s entry into the EU, which allows the European Commission to oversee the re-evaluation of judges and prosecutors in Albania.

Assessment of Xi-era Albania-China relations from the perspective of united front work activities reveals a familiar pattern with local variations, but it also shows how a small state can engage with China in a constructive way, while limiting potentially negative impacts of those interactions. Like many other small states in a geographically significant location, Albania is trying to avoid the mistake of becoming over-reliant on one great power, or becoming a pawn in a great power conflict. It is guaranteeing its security via relations with a broad number of diplomatic partners and by membership in multilateral organisations like NATO and the EU.

Albania has learned from the painful past, as has China. The two countries have a growing economic relationship, but the political relationship is unlikely to return to the levels of closeness of the 1960s. China’s united front work efforts may have succeeded to some extent, by creating a more positive atmosphere for investment and trade. Albania is partnering in economic cooperation beneficial to both China and Albania. But so far, Albania is holding back on strategic links such as permitting Huawei 5G in Albania or a Beidou ground station. Despite being a Muslim-majority nation, Albania did not join other Muslim-majority nations in signing a recent 37-country letter of support for China’s policies in Xinjiang. Albania sent a delegation to attend the Trump administration’s 2018 and 2019 Ministerial to Advance Religious Freedom, which built links with like-minded states via religion. The Albanian government has offered to host a follow-up “religious-freedom-focused conference” in the near future.

The words and actions of successive Albanian government’s over the last twenty-five years show that Albania’s core alignment lies in multilateralism, focused on NATO and the EU. Albania is not the only small state to have strong economic interests with China while its political interests lean elsewhere. If this is what the CCP calls a “traditional friendship”, then Albania-China relations in the Xi era are transactional at best.

Anne-Marie Brady is Professor in Political Science and International Relations at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand, and a Global Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC. She is a specialist in the politics of the PRC and the CCP’s Party-State system; as well as polar issues, Pacific politics, and New Zealand foreign policy.