With its growing military power and expanding economic influence, China believes it can dominate its neighborhood with superior hard power. Despite briefly championing a strategy of “smiling diplomacy” after the re-election of Xi Jinping as general secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in October 2022, China has since returned to its conventional assertive behavior.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has only perpetuated this trend. Asian countries have seen fit to strengthen their military deterrence based on the assumption that Ukraine was invaded because of insufficient power and weak security guarantees. The war has also shaken the region’s belief that economic interdependence (expectations of future economic benefits) reduces the probability of military conflict, which was once the basis of European countries’ relations with Russia.

Amid these shifting dynamics, Asian countries are attempting to strengthen communication with China in several ways, including with dialogue, by promoting pragmatic cooperation, and incorporating China into regional frameworks. But with Beijing focused on building a “new world order” that is not beholden to Western standards, it’s hard to predict how long Beijing will remain interested in the incentives of future economic benefits.

Simply put, China’s vision of win-win international relations is not convincing to regional powers interested in stability. Instead, China’s neighbors are focused on maintaining military deterrence while engaging in sturdy, patient diplomatic negotiations. This uneasy balance will not change unless Beijing acts as a responsible power, and not a superpower spouting empty promises.

This paper aims to untangle these developments. Among the top findings:

(1) China is trying to present itself as a responsible global leader that can replace the West, but in reality, Beijing has been gradually changing the status quo by utilizing hybrid challenges and widening the capabilities gap to help China seize regional hegemony unilaterally. This suggests China doesn’t represent the interests of developing countries and is not a responsible superpower. Escalation of tensions in the region has been narrowly averted by the patience of neighboring countries – not China’s actions.

(2) China’s behavior in contested regions in the East China Sea (the Senkaku Islands), the South China Sea, and around Taiwan can be divided into two categories: premeditated routines unlikely to be influenced by external influences, and ad-hoc actions aimed at expressing dissatisfaction with the actions of neighboring countries. Given this, diplomatic efforts alone will not lead to peaceful resolution of disputes with China.

(3) China’s economic presence and influence in the Indo-Pacific is expanding and deepening through trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) flows, especially in real estate, information technology (5G/6G networks), manufacturing (primarily electric vehicles), and financial sectors (Digital Yuan). As an increasing number of Chinese companies begin operating in ASEAN countries – drawn by lower labor costs and to avoid economic sanctions imposed by the United States – there’s a growing expectation that Beijing will want to maintain stable relations with its neighbors. Ensuring that Beijing respects economic interdependence theory is crucial to regional stability.

(4) In 2021, the 27 countries of the European Union recorded the second-largest share of FDI in ASEAN, putting the EU ahead of Japan and China. This indicates that for Europe, Indo-Pacific security is of critical national and regional importance.

(5) Indo-Pacific countries, and especially those in ASEAN, should be supported with capacity building programs to foster regional security and strengthen human development. At the same time, a multilayered regional mechanism involving China should be formed to manage the so-called “China risk.”

China, the Irresponsible (super)power

At home, President Xi Jinping promotes the “Chinese dream (中国梦),” his vision of national rejuvenation powered by a moderately prosperous society and socialist modernization. Internationally, on the other hand, he champions the concept of a “Community of common destiny for mankind: CCD (人类命运共同体).” This idea, officially written into the preface of the Chinese Constitution in 2018, rejects the unfair and unjust zero-sum game mentality of some countries, opposes bullying of small countries by large countries, and calls for international disputes to be resolved through dialog.

But the “common destiny” vision goes a step further: it rejects the post World War Two liberal international order shaped by the U.S. and European countries, and promotes a multipolar world divided and managed by each of the regional powers.

Xi characterizes China’s foreign policy as non-interference in domestic affairs, combining the distinctive socialist tradition of China with current practices in international relations. It is consistent with the characteristics of “Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy” (also known as “Xiplomacy”), which claims to lead global governance reform based on the principles of fairness and justice, and to advance a new world order that doesn’t rely on the balance of power principle. China seeks to achieve this new framework through close dialogue, including establishing hotlines, advocating mutual respect, and promoting win-win relations built through cooperative partnerships such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

In April 2022, China proposed the creation of the Global Security Initiative (GSI). Detailed in a concept paper released in February 2023, the GSI promotes respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, strengthening the role of the United Nations, and peaceful resolution of problems. In other words, China pretends to be a responsible power while criticizing the Western-led international order as “hegemonic” and born from a “Cold War mentality.”

Yet China’s preferred approach to global governance has so far failed to match the rhetoric; Russia’s aggression in Ukraine is a prime example. Because Beijing cannot free itself from its “sphere of influence” mindset – where the world is divided into regions and controlled by regional powers – Xi’s administration has been unable or unwilling to end the hostilities. This, despite Russia being a member of a Sino-Russian comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination. China’s failure in Ukraine has therefore disappointed the international community, and China’s image as the “next international leader after the West” has lost ground.

China’s “sphere of influence” logic is not new. On March 11, 2008, Admiral Timothy J. Keating, then commander of U.S. Pacific Command, testified before the Senate Committee on Armed Services that during his official visit to China in May 2007, a Chinese naval official (presumably Rear Admiral Yang Yi) suggested dividing up the Pacific Ocean between the U.S. and China. The Americans would assume control over the area east of Hawaii (the Eastern Pacific) and China would control the area west of Hawaii (the Western Pacific). Communication would be the only form of cooperation.

Another example of China’s arrogant power consciousness occurred in April 2013, when President Xi told then-Secretary of State John Kerry that “the vast Pacific Ocean is large enough to accommodate the two superpowers of China and America.” This mindset fundamentally contradicts the very foundation of CCD, in which “both large and small nations are equal” and denying to seek hegemony.

After Xi secured a third term as general secretary of the CPC, in October 2022, he began a campaign of so-called “smile diplomacy,” fueled by his confidence in China as a nuclear and conventional military power, and an economic heavyweight.

The first foreign leader to meet with Xi after his reappointment was Nguyen Phu Trong, general secretary of the Vietnamese Communist Party. The two leaders met in Beijing on October 31, 2022, and announced a joint declaration on strengthening and deepening overall strategic cooperation. The two countries agreed to accelerate ongoing negotiations on the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea (COC), which will establish fundamental principles of behavior by ASEAN’s 10 members and China.

The agreed framework for settling disputes in the South China Sea was a welcome development for the international community. Nguyen also struck a cooperative note by announcing Vietnam’s support for China’s application to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

Xi’s professed commitment to “Xiplomacy” has been a constant theme since his re-appointment. When Xi met with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida on November 17, 2023, the two leaders stressed the importance of building constructive and stable relations and agreed to establish a high-level Japan-China Security Dialogue as well as a hotline between defense authorities (scheduled to become operational by spring 2023). Another important step was the leaders agreeing that “nuclear weapons must not be used” in response to Russia’s nuclear saber-rattling.

Xi has also met Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., who took office at the end of June 2022. During that meeting Xi indicated his rejection of interference by external powers by asserting that “the two countries must uphold strategic autonomy, reject unilateral bullying by external actors, and safeguard regional peace and stability.” Xi proposed cooperation in infrastructure construction and the establishment of an industrial park through BRI, as well as an increase in imports of agricultural products from the Philippines. In response, Marcos said that the two countries should continue friendly negotiations to resolve their differences over the South China Sea, and “the maritime issue alone cannot define the entire relationship between the Philippines and China.”

Despite Xi’s commitment to peaceful resolution of differences, China does interfere in the internal affairs of its partners through economic coercion and other means. Increasing military spending without transparency, beefing up conventional and nuclear forces, and expanding the military activities of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (including the coast guard, maritime militias, and oceanographic research ships) are evidence that China wants to challenge U.S. hegemony with force, pursuing “the Cold War mentality” that it publicly rejects. While this may be an attempt to divert domestic frustration away from the Party – particularly over its handling of the COVID-19 pandemic – the fact remains that Beijing’s assertive behaviors in the Indo-Pacific undermine Xi’s “smiling diplomacy” and tarnish China’s image as the “next international leader after the West.”

Security in the Western Pacific

An analysis of China’s behavior in the East China Sea, around Taiwan, and in the South China Sea shows that while China’s provocations have increased overall, the tactics differ significantly between regions due to different security structures and the density of regional deterrence.

For instance, while China’s behavior in the East China Sea has been relatively restrained in terms of provocations, there has been a dramatic increase in threats by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) military aircraft and warships around Taiwan and in the South China Sea. Provocations against Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines by survey ships, Chinese Coast Guard (CCG) vessels, and marine militia boats have also increased.

This is because the South China Sea is the easiest maritime area for China to act unilaterally. China’s southern neighbors have no reliable defense alliance or security framework and are vulnerable to China’s military and national power. Given this, it’s reasonable to expect that China’s assertive behavior in the South China Sea will increase in parallel with its challenges around Taiwan.

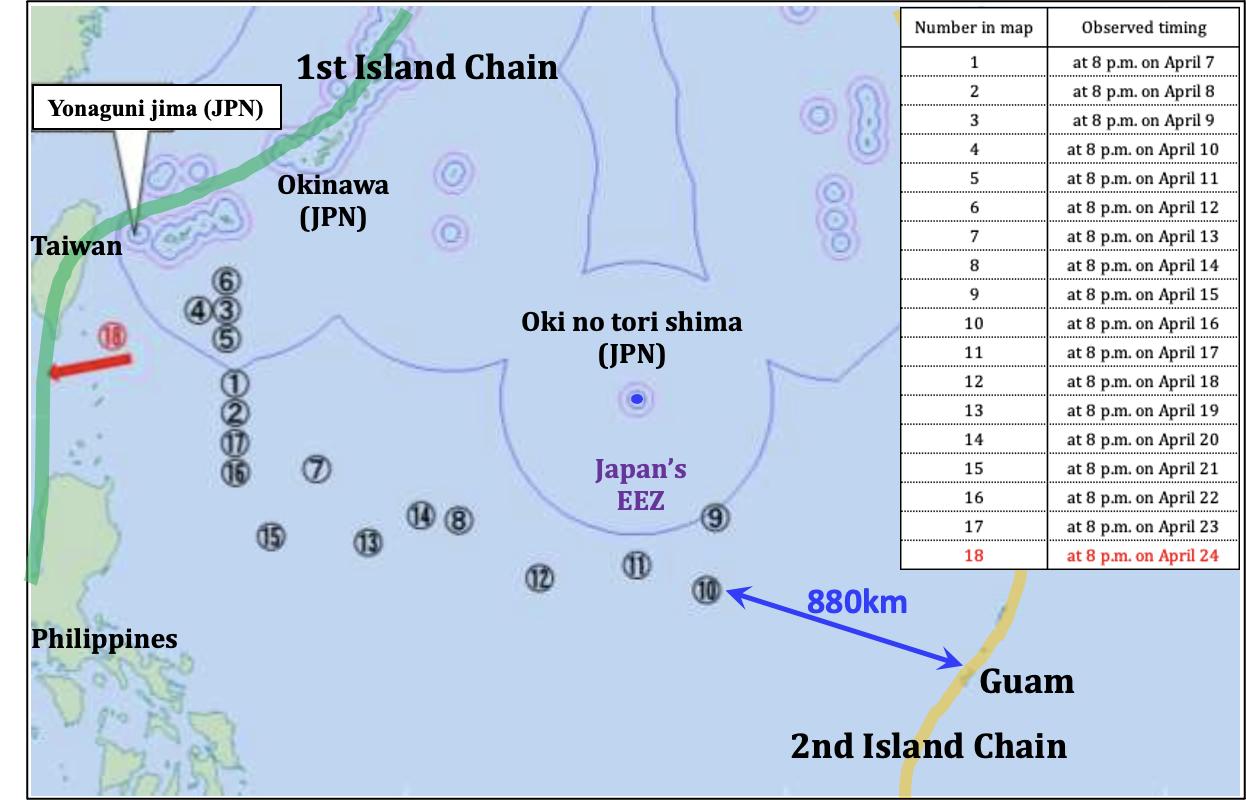

Tensions are also high in the East China Sea, where China and the Japan-U.S. security alliance stand opposed, concentrating massive deterrence to contain the other side. Further evidence of U.S.-China power competition can be seen in the Chinese military expansion from the First Island Chain into the Second Island Chain (See Map 1).

Map 1: Exercises conducted by the People’s Liberation Army Navy Shandong carrier group in April 2023

(Source: Prepared by the author based on Japan Joint Staff Office: JSO)

China’s actions are being guided by both domestic political institutions and agencies under the CPC, and as punitive measures against its neighbors. As such, it’s necessary for neighboring countries to recognize that diplomacy alone may not be sufficient to improve bilateral relations.

For example, on May 8, 2023, Beijing deployed a research ship, the Xiang Yang Hong 10 (XYH-10), to Vietnam’s natural gas mining block 04-03, which is within the country’s exclusive economic zone: EEZ. But even after the Vietnamese made an official request on May 25 for China to withdraw their vessel, Beijing refused the request and finally the vessel left from Vietnamese EEZ on June 5.

In short, China pretends to be a “responsible regional power” but ignores the concerns of its neighbors when it’s beneficial to do so. This is because China believes that no matter how coercive ASEAN countries are, they don’t have the economic or military power to oppose China’s writ.

(1) East China Sea: An increasing frequency of challenges

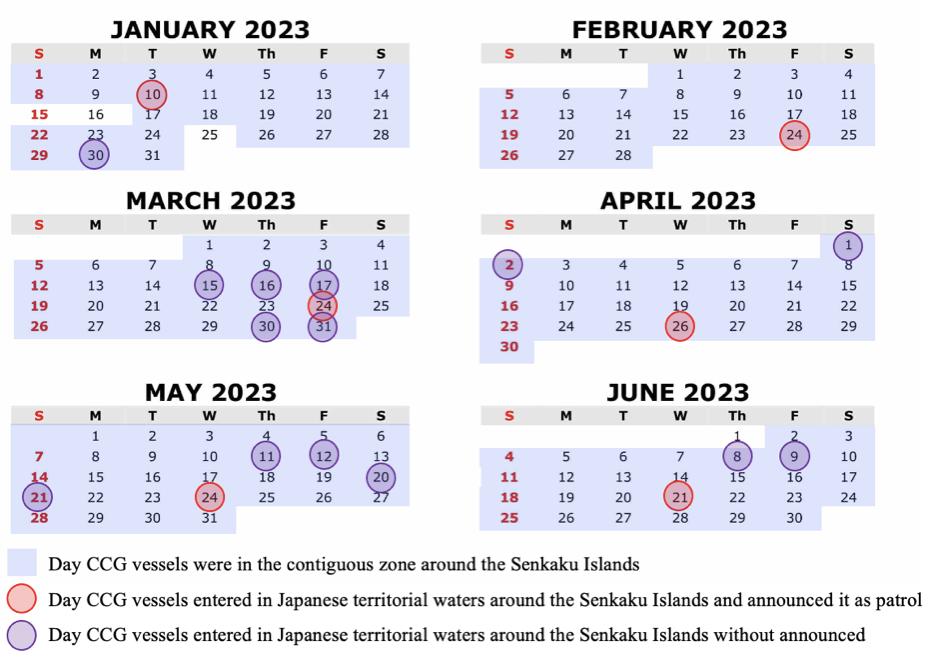

In the first half of 2023, regular intrusions by Chinese Coast Guard vessels into Japan’s territorial waters surrounding the Senkaku Islands maintained the “4-1-2” formula (four incursions per month, each lasting for two hours or less). At the same time, irregular intrusions by the CCG to track Japanese fishing vessels and monitor fishing activities around the Senkaku Islands have increased in frequency (See Image-1).

For instance, between March 30 and April 2, CCG vessels tracked a Japanese fishing boat and stayed in Japan’s territorial waters for more than 80 hours – the longest incursion in history. CCG vessels also tracked a Japanese research ship on January 30 as it was conducting an annual environmental survey near Ishigaki island. These and other incursions suggest that China wants to exercise effective control over the islands in a bid to illegally secure jurisdictional rights.

Image 1: CCG Vessels Around the Senkaku Islands

(Source: Prepared by the author based on Japan Coast Guard data)

In particular, CCG vessels, which had typically turned off their AIS (automatic identification system) before entering Japan’s contiguous zones or territorial waters, are increasingly navigating with their AIS switched on.

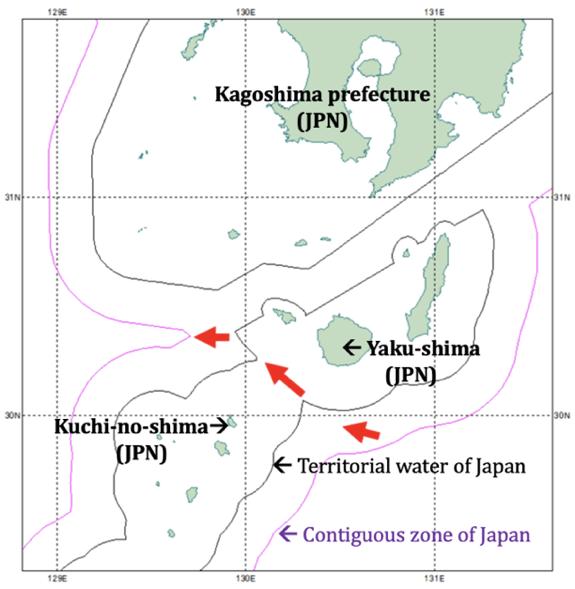

In addition, the Shupang (636A/B), People’s Liberation Army Navy survey vessels, are increasingly violating Japan’s territorial waters between Yaku-shima Island and Kuchi-no-shima Island, claiming the water as an international strait (despite Tokyo’s insistence to the contrary). The first violation was observed in November 2021. There were five violations in 2022 and two through June 2023). China is believed to be researching the waterway for possible navigation by navy submarines.

Map 2: Violation of Japanese Territorial Water by People’s Liberation Army Navy Survey Ships

(Source: Prepared by the author based on Ministry of Defense press release in Japanese, June 8, 2023)

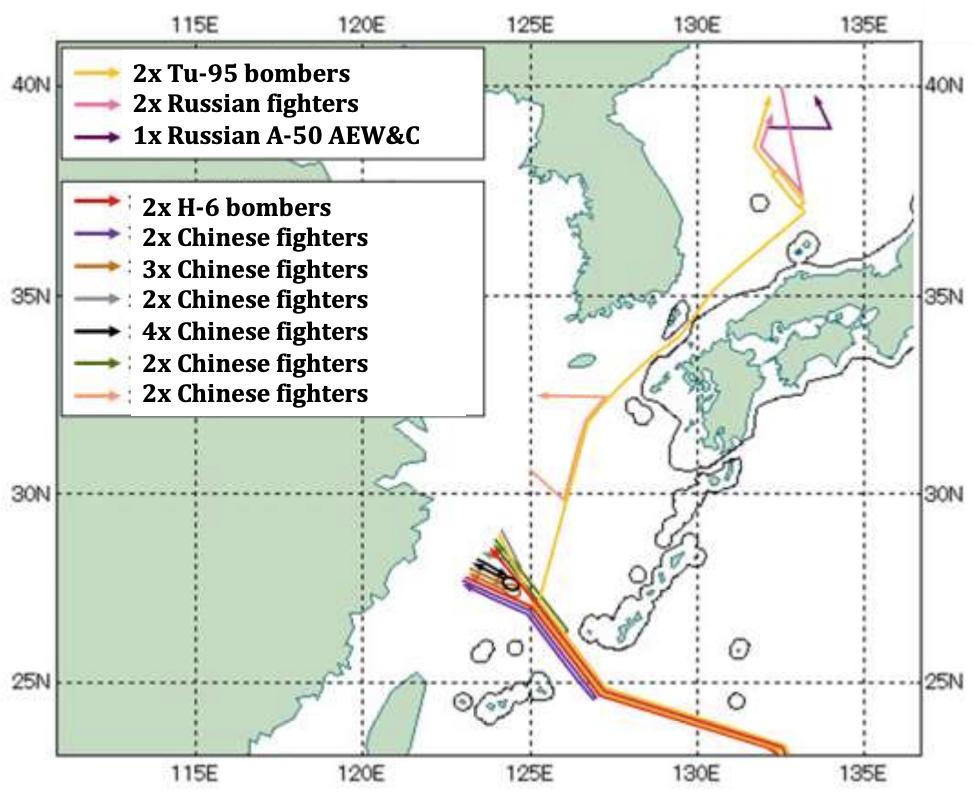

China is also raising concerns in the air. Joint “strategic patrol” flights by nuclear attack-capable Chinese H-6K and Russian Tu-95MS strategic bombers, which escort fighters over the Sea of Japan, the East China Sea, and the Western Pacific, have increased from once a year (first observed in July 2019) to twice a year in 2023. In June 2023, strategic patrols were conducted on two consecutive days for the first time ever (See Map 3).

Sino-Russian patrols are part of the countries’ Military Cooperation Roadmap for 2021-2025, which includes joint maritime military exercises in the Sea of Japan and strategically coordinated action at the UN Security Council. But as Russian strategic bomber operations during the war in Ukraine suggest, while valuable for launching cruise missiles (such as Russian Kh-55 and Kh-101/102 and Chinese HN-3C/KD-20, with a range of 2,000 to 3,000 kilometers) they are also vulnerable and must be operated in a safe position far from territory of enemy.

It is therefore believed that Sino-Russian patrols during peacetime are for the collection of information on air defense radar and sensors operated by Japan’s Self-Defense Forces and U.S. Forces Japan, as well as to demonstrate operational unity.

Chinese and Russian bombers have also penetrated South Korea’s air defense identification zone (ADIZ) over the Sea of Japan. Closer cooperation between Japan and South Korea in military intelligence could enable more detailed analysis of these incursions.

Map 3: Flight path of Chinese and Russian strategic bombers on June 7, 2023

(Source: Prepared by the author based on Japan Joint Staff Office press release in Japanese, June 7, 2023)

(2) Taiwan: Challenging Taiwan’s Military Response Capabilities

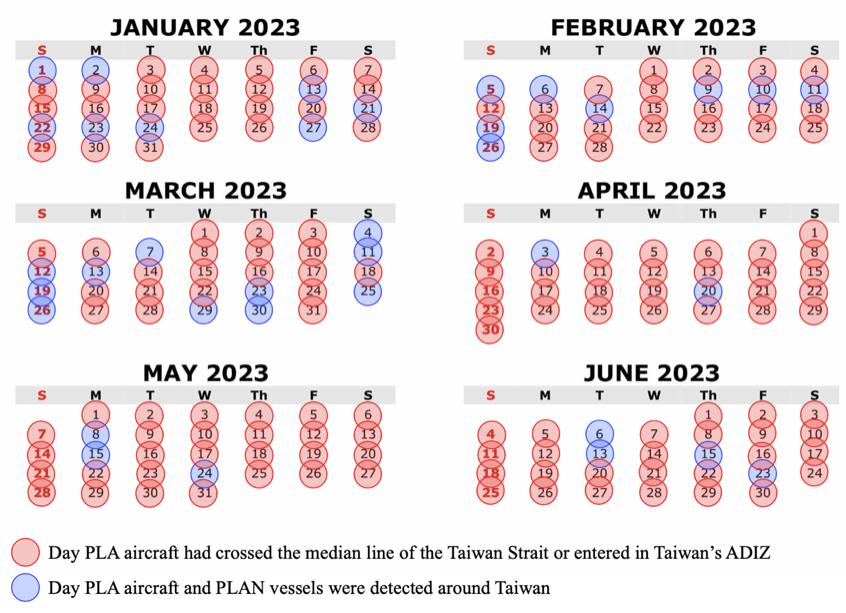

Since the visit of U.S. Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi to Taiwan in August 2022, flights by PLA military aircraft across the median line in the Taiwan Strait have been accelerating. An analysis of the movements of Chinese military aircraft and naval vessels, categorized by color on the calendar (See Image 2), shows that Beijing has increased its military pressure on Taiwan to express its dissatisfaction with Taiwan’s foreign policy. Incursions are linked to President Tsai Ing-wen’s trip to the U.S. on April 5 to meet current House Speaker Kevin McCarthy. The days circled in red are days when Chinese military aircraft crossed the median line or entered Taiwan’s air defense identification zone. The blue circles indicate days when Chinese military aircraft or warships were observed near Taiwan (but not over the median line).

Image-2: Presence of PLA aircrafts and vessels around Taiwan

(Source: Prepared by the author based on data released by Ministry of National Defense of Taiwan)

Compared to January, February, and March, when flights across the median line occurred about 20 days a month, since April, 28 days of overflights have been confirmed. Chinese military aircraft have also been entering the Taiwanese air defense identification zone almost every day.

As a result, flight times for Taiwanese Air Force aircraft have increased and the planned lifespan for each aircraft has gotten smaller. Thus, the challenge by the Chinese military can be viewed as psychological warfare against Taiwanese society, with the objective of degrading the responding capabilities of the Taiwanese military.

In addition, there were training activities in the Western Pacific by Chinese aircraft carriers Liaoning (CV-16) in December 2022 and Shandong (CV-17) in April 2023, with training for take-off and landing in waters close to Guam (between 770 and 880 kilometers; see point no. 18 in Map 1). There has also been an increase in training activities in eastern Taiwan, which should be recognized as preparations to block and isolate Taiwan from all sides in the event of a Taiwan contingency.

(3) South China Sea: No More Smiles

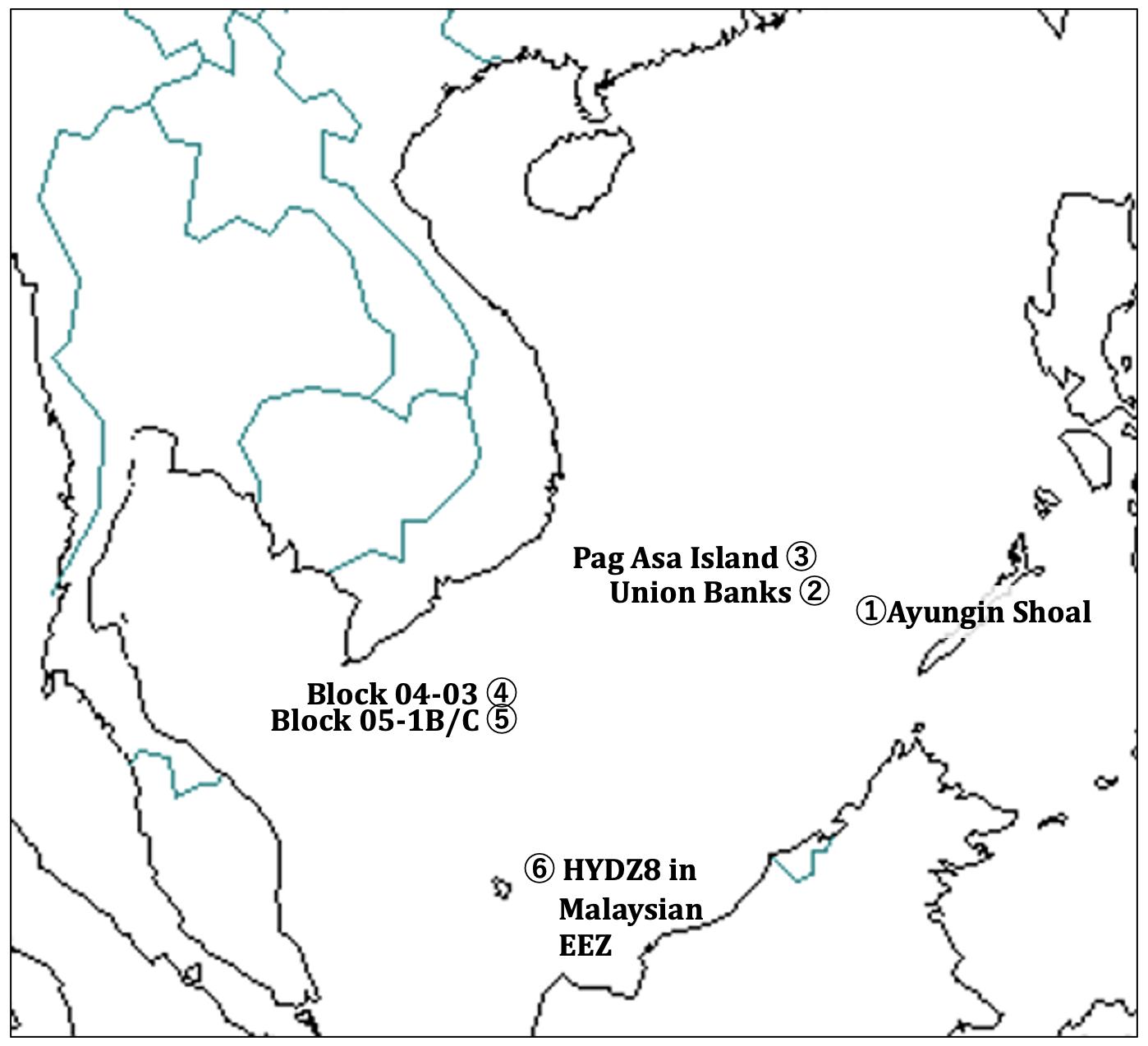

The situation in the South China Sea, which was relatively stable in 2022, has become tense once again. Since February 2023, CCG vessels with maritime militia boats have interfered to prevent logistical support to the Philippine’s outpost (BRP Sierra Madre) on Ayungin Shoal (See point no. 1, Map 4), where the Philippines claims sovereignty. On June 30, eight Chinese maritime militia boats escorted by CCG 3103 blocked the shoal and prevented access by Philippines resupply boats. This came after a CCG vessel, on February 6, irradiated a Philippine Coast Guard patrol vessel off Ayungin Shoal with a military-grade laser strong enough to cause temporary damage to crew members’ eyesight.1

CCG vessels have also gathered inside Union Banks (See point no. 2, Map 4), where the Philippines and Vietnam claim sovereignty over part of the shoal, and around Pag-asa Island (Point 3, Map 4), territory of the Philippines. China’s pressure on the Philippines has grown since the Philippines signed the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement with the U.S. on February 28.

In addition, the Chinese research vessel Xiang Yang Hong 10 (XYH 10), escorted by CCG 5305 and maritime militia boats, approached Vietnamese natural gas blocks 04-03 (Point 4, Map 3) and 05-1B/C (Point 5, Map 4) in Vietnam’s Exclusive Economic Zone on May 8, intimidated Vietnamese commercial operations, and on May 25, ignored a request by the Vietnamese Foreign Ministry to vacate the area.

Finally, the Chinese research vessel Haiyang Dizhi 8 (HYDZ8), which harassed the Malaysian drillship West Capella in that country’s EEZ in April 2020 (Point 6, Map 4), has reportedly been in the South China Sea since June 20 conducting undersea resource survey operations without Malaysia’s consent. The Royal Malaysian Navy has deployed its auxiliary support ship, Bunga Mas Lima, to observe Chinese vessels.

China unilaterally enforced a fishing ban in the South China Sea from May 1 to August 16, as it had in previous years. But China has no authority to ban the activities of non-Chinese fishing vessels. China’s basis for claiming 90 percent of the South China Sea was rejected by a court ruling in 2016, a decision that was reaffirmed at the G7 Hiroshima Summit in May 2023 and the Japan-U.S.-Australia Defense Ministers’ Meeting on June 3. Beijing, however, has ignored the ruling and is proceeding to turn the South China Sea into an extension of its territorial waters.

Map 4: Standoffs engaged by Chinese vessels in the South China Sea

(Source: Prepared by the author based on data released by Ray Powell and CSIS)

Deepening regional economic interdependence with China

Since 2009, China has been the largest trade partner of Japan, Australia, and South Korea. ASEAN countries also have become increasingly dependent on China. For instance, Vietnam, Thailand, the Philippines, and Cambodia have achieved rapid economic growth by fostering domestic industry with direct foreign investment. Each has adopted a model of importing materials and intermediate parts and components from China, processing and assembling them domestically, and exporting the final products to the U.S. and elsewhere. China’s role as a supplier of low-cost parts and materials to Asia cannot be replaced by the U.S., even with Washington promoting the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF).

The importance of China’s economy to ASEAN countries is evidenced by the amount of foreign direct investment within the bloc. While China’s official development finance (ODF) to Southeast Asia dropped to $3.9 billion in 2021, about half of its peak of $7.6 billion in 2015, Chinese spending in the region remains significant.

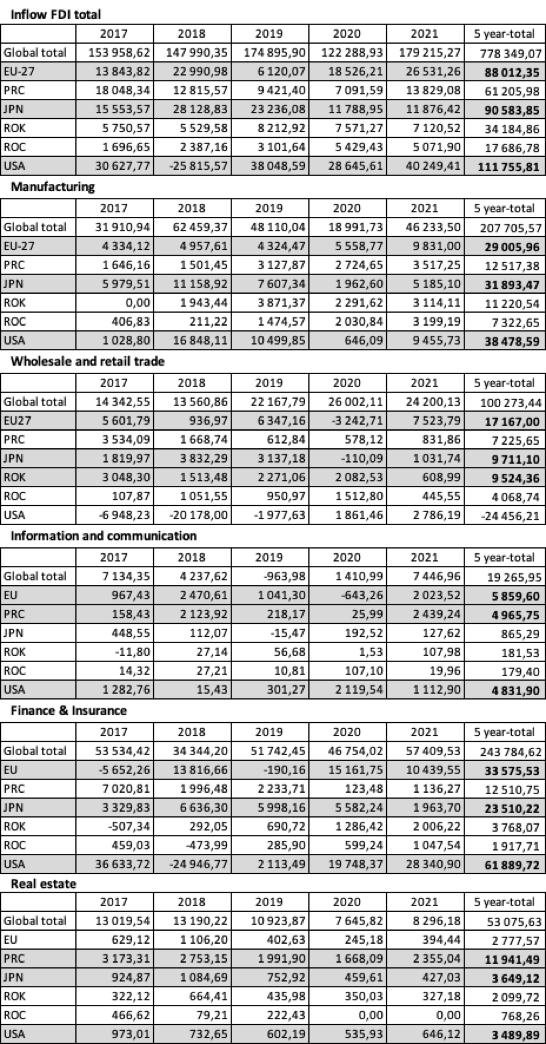

Still, China isn’t the region’s biggest investor. Data from ASEAN (See Table 1) show that China’s cumulative FDI for the five-year period from 2017 to 2021 was $61.2 billion, putting it fourth behind the EU ($88 billion), Japan ($90.5 billion), and the U.S. ($111.7 billion).

Table 1: Flows of Inward Foreign Direct Investment to ASEAN (in million US$)

(Five-year cumulative totals for the top three countries/regions are highlighted in gray. Source: ASEANStatsDataPortal, https://data.aseanstats.org/fdi-by-sources-and-sectors)

Of particular interest is the EU’s contribution. As a major investor in ASEAN, the bloc’s 27 countries could create a unified approach to neutralize China’s expansion. That will be easier said than done, however. Western companies are not state-run enterprises and invest based on their own profit calculations. As such, governments’ ability to influence investment is low, and contrary to the principles of free trade.

Investment trends in ASEAN vary by country. China’s investment in real estate accounts for a large portion of its total investment, but spending in the information and telecommunications sector, including 5G networks, has been increasing along with manufacturing, especially in electronics and electric vehicles.

China’s policies are raising concerns. Topping the list is Beijing’s rollout of a digital yuan (e-CNY), which could undermine the position of the US dollar as the international reserve currency. Other trouble spots include expansion of China-led e-commerce markets into ASEAN, data and privacy protection regulations, and standards for 5G/6G and other related technologies that are being negotiated as part of the ASEAN-China FTA 3.0 upgrade.

At the same time, the number of companies that have moved production from China to other Southeast Asian countries has increased. Statistics from the Japan External Trade Organization’s (JETRO) Vietnam office illustrates the scope of investment by Chinese companies (See Table 2). In 2021 and 2022, approved Chinese FDI projects related to the electronics industry were valued at $900 million The main reasons for the shift include rising tensions between the U.S. and China, and the impact of China’s strict COVID-19 lockdown measures.

But there are also structural issues at play. For example, the tariff rate between the U.S. and China, which was 3.1 percent in January 2018, now stands at 19.3 percent, a surge attributed to the China-U.S. trade war. Real estate and labor costs in China have also risen sharply. A JETRO survey found that the average labor cost in Shenzhen rose from USD $204 in 2008 to $564 in 2021.

In many cases, production that relocated from China to other ASEAN countries continues to rely on the Chinese supply chain, and as a result, economic ties between China and other ASEAN countries are deepening .

Table-2: Approved major electronics-related manufacturing FDI projects in Vietnam, 2021-22

(Chinese projects are highlighted in gray. Source: Regional analysis report, JETRO, April 25, 2023)

ASEAN countries recognize that access to China’s supply chain and the U.S. consumer market are driving current growth and providing resources for future growth. At the same time, they want to leverage America’s military presence to maintain a balance between China’s regional antagonism and economic power. For example, China’s aggressive attempt to unilaterally change the status quo in the South China Sea and its penetration into other ASEAN countries, such as the Ream Naval Base Modernization Project in Cambodia, pose security concerns for neighboring countries.

In other words, because China and the U.S. are necessary partners for ASEAN countries, regional actors want to see tensions between the two powers kept to a minimum. Furthermore, an increase in the number of Chinese companies entering ASEAN could also be strategically favorable for ASEAN, since maintaining stable relations with ASEAN countries is an important goal for China. Regional stability can also be secured and maintained by inviting other external players – such as Australia, Japan, India, and European countries – to neutralize the growing economic and political influence of China.

Before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it was widely assumed that deepening energy and economic ties between European countries and Russia would reduce the probability of military challenges by Russia, primarily because the economic benefits of interdependence would outweigh anything gained in war. However, Russia’s actions have cast doubt on the protective value of interdependence. While a strong Western response to Russia’s “special military operation” was always possible, Putin calculated that the strategic opportunity for Russia outweighed the potential losses from European countries.

China’s calculus is more complicated. If Beijing were to attempt a military annexation of Taiwan, and if Western countries were to introduce severe economic sanctions against China (as they did against Russia), Xi Jinping would have to anticipate restrictions of Chinese trade, and risk losing the demand for Chinese products in Western markets.

Furthermore, a decline in imports of oil and other resources that pass through the Strait of Malacca, as well as subsequent disruptions in the supply chain, cannot be replaced by increased imports from Russia alone. Beijing’s “great internal circulation” economy would be hindered. In this context, persuading ASEAN countries to join in possible economic sanctions against China would be crucial for the West.

However, if a final resolution of the Taiwan issue is strategically valuable to Xi, not even the threat of sanctions will dissuade him. The only way to change Xi’s mind would be by developing and securing a strong military deterrence. At the moment, however, it’s China that is building up military power more than any other country.

A Widening Power Gap Between China and its Neighbors

In addition to China’s growing economic influence, another serious concern is the increasing gap in military power between China and its neighbors. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s (SIPRI) Military Expenditure Database, China’s estimated defense spending in 2021 was 1,892.7 billion yuan ($293.3 billion), up 6.8 percent from the previous year, and 36 times more than what was spent 30 years ago. Beijing is trying to catch up to the U.S. in military expenditures ($800.6 billion), and spends more on its military than Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and India combined.

Japan’s defense budget was $54.1 billion in 2021. The Kishida administration has moved to increase defense spending to about 43 trillion yen (USD $318 billion) by 2027, roughly 2 percent of GDP. Although this would put Japan in line with NATO countries, it is nowhere near the rate of China’s increase. The total defense budget of the 10 ASEAN countries in 2021 was about $43.4 billion (figures for Laos and Vietnam are estimates), which is only about 15 percent of China’s officially announced defense budget.

In addition to increasing defense spending, Beijing is highly motivated to develop a fully modernized, world-class military by 2027, the 100th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Liberation Army.2 This is also part of a military reform process initiated by Xi. In November 2015, he announced the creation of a new military branch, the “Strategic Support Force” (SSF), tasked with running space platforms and waging cyber information warfare. The SSF is independent from the Army, Navy, Air Force, and the PLA’s Rocket Force.

In addition, “intelligent warfare” has been explored to speed up decision-making and reduce uncertainty on the battlefield. This will coordinate the collection, analysis, and sharing of information across multiple domains, and integrate advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI). The PLA is also pursuing “Military-Civil Fusion” (MCF), which aims to make technological breakthroughs by synergistically combining civilian and dual-use technologies in a wide range of fields, including drones and drone control technology – such as swarm operations, AI, and other disruptive technologies. These efforts are part of long-term preparations for the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

In contrast, most ASEAN countries’ militaries are tasked primarily with responding to threats from non-state actors, maintaining internal security, contributing to peacekeeping, and responding to disasters. They have neither the equipment nor strategic skills necessary to counter modern Chinese military power.

In recent years, China has been strengthening its capabilities by utilizing tactics called “maritime hybrid warfare.” This can be defined as “an attempt to change the status quo in the maritime domain for specific strategic goals, conducted through the mixed use of military and non-military means that are difficult to recognize, under the threshold of open conflict.” The means used for this type of warfare are not “gray hulls” (Navy vessels), but “white hulls” – patrol vessels of the maritime law enforcement agencies, government research vessels – and drones. This type of warfare includes challenges to other nations’ sovereignty, sabotage, attacks on infrastructure such as undersea cables, and the obstruction of maritime trade routes.

The China Coast Guard (CCG), which is under the command of the People’s Armed Police and directly controlled by the Central Military Commission since 2018, has been enhancing its maritime law enforcement capabilities, not only in terms of equipment but also in the professionalism of its crews and the sophistication of its operations.

To date, the longest sailing for a CCG vessel in Japanese territorial waters around the Senkaku Islands was 65 hours and 15 minutes, recorded on July 5, 2022. China Coast Guard ships are also logging more consecutive days stationed around the islands, reaching 336 consecutive days in 2022. And, just as China denies economic activities by neighboring countries within the so-called “Nine-Dash line” of the South China Sea, CCG vessels are increasingly harassing Japan’s fishing activities around the Senkaku Islands.

Furthermore, government vessels for non-commercial purposes, such as coast guard vessels and oceanographic research vessels operated by government agencies, institutes, and universities, are exempt from the jurisdiction of any state other than the flag state, making on-site inspection and capture impossible on the high seas.3 Aware of this, China frequently uses research vessels to conduct surveys in other countries’ exclusive economic zones without prior consent or notification. China has the largest fleet of oceanographic research ships, and their survey areas have expanded to distant ocean areas such as the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean (especially the waters around Guam), where submarine communication cables between the U.S., Asian, and Pacific states are laid.

China is the world’s leading drone producer, and its use of military unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) is also increasing. Unlike manned aircraft, drones pose no risk to their human operators. UAVs can be operated continuously for long periods of time and have a high degree of operational flexibility, as the war in Ukraine has demonstrated (although the effectiveness of UAV was recognized worldwide during the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War in September 2020), including patrol and surveillance missions over a wide area of ocean.

According to a news release from the Japanese Joint Staff Office, the first recorded Chinese drone operation in the East China Sea was reported in airspace near the Senkaku Islands on September 9, 2013. After a small commercial drone was observed in May 2017, there was no sign of Chinese drone activity for several years. Since 2021, however, there has been a significant increase in Chinese UAV operations. In particular, the TB-001 UAV, which had previously flown alongside manned aircraft, flew alone through the Miyako Channel toward the Pacific Ocean in July 2022, then returned to mainland China.

Similarly, on August 4, 2022, after U.S. Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan, TB-001 and BZK-005 UAVs with reciprocating engines flew individually from mainland China for a total of 3,200 kilometers to observe missile exercises around Taiwan. This means that China has established a long-range UAV reconnaissance system that also reliant on its space infrastructure. Furthermore, in January 2022, China reportedly deployed a WZ-7 jet UAV with a top speed of 750 km/hour and a range of 7,500 km to Hainan Island. An image of the naval variant WZ-7 was released in March 2023 by the Chinese navy.

In addition to UAVs, China also conducted maiden autonomous sea trials of a 200-ton unmanned surface vessel (USV) in June 2022. Beijing unveiled the HSU-001 Large Displacement Un-crewed Underwater Vehicle (LDUUV) during a military parade in October 2019, and Naval News reported that two types of Extra-Large Un-crewed Underwater Vehicles (ELUUV) are being tested on Hainan Island. Various Chinese companies are working intensely to develop different types of drones, and Beijing’s military-civil fusion is paying off.

In response to the growing challenge from China that now includes maritime hybrid warfare, the administration of Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida approved a National Security Strategy (2022NSS), National Defense Strategy (2022NDS), and Defense Buildup Program (DBP), all shaped by the National Security Council, on December 16, 2022. The documents indicate Tokyo’s willingness to raise its defense budget, even though Tokyo has struggled to find the means to secure the funds. ASEAN countries, which have limited defense budgets, have been slow to respond. The gap between China’s capabilities in the South China Sea and those of ASEAN countries is even larger than the gap between Japan and China in the East China Sea. Therefore, it is essential to support ASEAN countries in capacity building for maritime law enforcement capabilities and maritime domain awareness (MDA), which involves early detection, analysis, information-fusion, and information-sharing of unusual activities by vessels and drones.

Integrating China into Regional Frameworks Remains a Priority

China’s attempts to change the status quo by force and economic coercion must be deterred, and regional stability must be maintained. Patriotism and Han-centric nationalism are, of course, important and legitimate considerations for a Chinese leader, but ultimately his success depends on providing food, clothing, shelter, and other basic necessities for his people. The fact that the Chinese Politburo reversed its zero-COVID policy after a “white paper protest” broke out shows that the country’s leadership is attuned to the discontent of its citizens. As such, economic and social interests that the Chinese people share with neighboring countries are likely to influence decisions made by the Chinese leadership.

To this end, Asian countries are trying to incorporate China into multilateral frameworks. Their efforts include practical cooperation for shaping complex interdependence, and establishing a “tension management mechanism,” with networks of hotlines and dialogue through multiple channels (especially informal dialogue, which is characteristic of Asia) in tandem with the development of deterrence and security architectures.

For example, the Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defense Ministers Meeting-Plus (ASEAN 10 plus eight countries, including Japan, the U.S., and China) held on November 23, 2022, called on participating countries to comply with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and other maritime norms to avoid accidental collisions.

At the 29th Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting in November 2022, the participants reaffirmed the principle that cooperation is essential for the growth and future of the Asia-Pacific region. Compliance with international law is essential for promoting multilateral cooperation, and in this context, UNCLOS is the fundamental legal agreement that defines the obligations, rights, and behaviors of all users of the oceans. Because of China’s tendency to interpret UNCLOS provisions and definitions exclusively in its favor, and modify UNCLOS to suit its national interests, the international community is trying to persuade China to respect the existing international legal system.

Moreover, in the context of bilateral relations, there have been increasing attempts by neighboring countries to make China recognize the benefits of cooperation through pragmatic approaches that offer incentives to maintain stability. The first foreign leader with whom Xi met after he was re-elected was Nguyen Phu Trong, General Secretary of the Vietnamese Communist Party. The two leaders announced a joint declaration on strengthening and deepening overall strategic cooperation and agreed to accelerate ongoing negotiations on the Code of Conduct (COC) in the South China Sea, which will establish fundamental principles of behavior in the waterway by ASEAN 10 members and China. Vietnam also has been actively addressing maritime security, particularly emphasizing the importance of UNCLOS and advocating peaceful resolution of maritime issues through international law and diplomacy.

Although Vietnam’s military capabilities are far inferior to China’s, it would be a mistake to interpret Vietnam’s efforts as a sign of weakness. Rather, they reflect its policy of diversified diplomacy, which was strengthened by a defense equipment and technology transfer agreement with Japan in September 2021 and a mutual logistics agreement with India in June 2022. In this respect, we can learn from the flexible and pragmatic stance of the ASEAN countries, which are promoting pragmatic relations with China by strengthening ties in areas where cooperation is possible while firmly pointing out China’s problematic stances and actions to the international community.

Indeed, this approach is in sync with the pragmatic, flexible, and multifaceted approach stipulated in the EU’s Indo-Pacific document. In this context, the negotiations on the COC between China and ASEAN should be continued, even though several ASEAN members were unsatisfied with practical implementation of the Declaration Of Conduct (DOC) in 2012.

Conclusion

Behind China’s smiling diplomacy is a menacing glare. To respond to China’s unilateral and aggressive behavior, ASEAN needs the security support of external actors and must also strengthen its own coping capabilities to coordinate the political will and military power of its member states.

There are several forms this can take, including strengthening relations with India, with which ASEAN conducted its first joint naval exercise on May 8; improving coordination with the U.S., whose aircraft carrier USS Ronald Reagan made a port call in Da Nang, Vietnam, during the last week of June; and enhancing ties with Japan, which has supported maritime law enforcement capacity building in several ASEAN countries. An ASEAN naval search-and-rescue operation, planned for September 2023 under Indonesia’s initiative, in another way ASEAN is demonstrating unity and alignment.

Beyond strengthening ASEAN’s capabilities, regional governments must continue to both engage China and sound the alarm about Beijing’s assertiveness and unilateral behavior. Whenever possible, these messages must be delivered to the international community in real-time.

Security relations between the U.S. and its allies have been strengthening not only through bilateral forms but also “mini-lateral” means, fueled by the active participation of countries like South Korea, the Philippines, and Canada. The involvement of these smaller states has been brought about by China’s unilateral actions and requests for greater international involvement in the Indo-Pacific. A similar scenario played out in Europe, with Central and Eastern European countries’ eagerness to assist NATO following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

This has left China increasingly isolated internationally. Without Russia as a reliable ally, China wants to change the status quo with escalation and salami-slicing tactics. Its objective is to eliminate U.S. influence in the Indo-Pacific and throughout the Global South. But this approach has created a gap between China’s self-image and the international community’s evaluation of China. In the absence of friends, Beijing seeks to secure its authority through violence and intimidation.

It’s essential that Europe, together with the U.S., Japan, Australia, and ASEAN countries, collectively reject China’s efforts to upend the status quo through force and economic coercion. To succeed, multiple regional frameworks are needed, in which large and small countries are treated equally, and no single country has an advantage – China included. Promoting pragmatic regional cooperation that includes China will help secure the common social and economic benefits of the status quo and maintain the complex interdependence that drives the Indo-Pacific region.