Also available for download.

The III World Congress of the Comintern began the turn toward ‘Einheitsfrontpolitik’ […] a concept that permitted the Communist parties to preserve their revolutionary identity in non-revolutionary times.

— on Ernst Meyer, KPD chairman 1921-1923.1

Some foreigners with full bellies and nothing better to do engage in finger-pointing at us. First, China does not export revolution; second, it does not export famine and poverty; third, it does not mess around with you. What else is there to say?

— Xi Jinping in Mexico, 2009.2

Introduction

“What else is there to say”? A decade after Xi Jinping’s acerbic comment in Mexico, it turns out quite a lot.

China may not be exporting revolution in the commonly-understood sense of the word, but it is exporting major change. Most visibly this is afoot via the geo-economic and strategic “Belt and Road Initiative”, but also via a revival, since 2015, of the united front, a 100-year-old project launched by the Third Communist International in Europe in 1921 and later brought to China, where it went through several iterations. Potentially significantly, there are efforts underway to “sinify” the united front and justify it within the context of “traditional Chinese culture”, even connecting it to the philosophical worldview of “tianxia 天下”, or “all under heaven”.3

The “Einheitsfront” enabled European Communist parties “to preserve their revolutionary identity in non-revolutionary times“; Xi Jinping’s 2015 call to build a “broadest (possible) patriotic united front” is attempting to preserve and extend the CCP by upping ideological influencing, not just in China but around the world, including in Germany.4 And as in Europe in the 1920s, today’s activities may reflect a push for survival by the party in a relatively hostile international environment. The party is determined to continue its power monopoly inside China, and to do that, it believes it must extend it outside China, in order to remove challenges. So arguably, China does “mess around with you”. It might even be exporting revolution, in the sense of major change.

Few sinologists or even politics experts in Germany seemed aware of the presence, or increasing spread, of the united front in Europe, I realized on returning to Berlin in 2017. Sensitized to the political language and culture of the CCP after decades in China and Hong Kong, it leapt out at me via images, Chinese language media reports, and personal interactions, in business, culture, professional, technology and politics networks, German-Chinese friendship associations, and Chinese student and scholar associations. With the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 awareness of Leninist politics had fallen too; the Cold War was “over”, West Germany had incorporated East Germany and the experience of dictatorship in the former DDR (Deutsche Demokratische Republik) became a historical artefact rather than a continuing reality (albeit elsewhere), certainly not one that anyone thought could affect Europe. By 2018, decades of enthusiastic relations with China had yielded vigorous trade figures: Germany exported 93.7 billion euros to China, about four times as much as Europe’s second-largest exporter, the United Kingdom (23.4 billion), or France (20.8 billion).5

Starting early 2019, using scores of authoritative Chinese and German sources to track formal meetings and personnel interactions with United Front organizations, I arrived at a baseline number of over 190 Chinese groups in Germany with direct ties to the United Front bureaucracy in China. I identified another, nationwide, German organization with 37 affiliates (including full members, waitlisted ones or those in other relationships with the umbrella organization), that partners with a key CCP influencing organization (thereby both facilitating and carrying out “united front style work”, 统战性工作, perhaps unbeknownst to its members).6 Add on about 80 Chinese Student and Scholar Associations, more than 20 Confucius Institutes and classrooms, a dozen united front-aligned, Chinese-language media (the figure depends on how one counts channels and their offshoots, so-called “traditional” and “new” media), an as yet unknown number of “Chinese Aid Centers” (华助中心) and the phenomenon is both large and complex. There are hundreds of groups working in Germany to maintain the CCP’s ideology, values, language and goals to varying degrees among a relatively small Chinese diaspora, and, importantly, more broadly in society from the grassroots to the elite.7 Europe-wide, these groups are embedded throughout civil society – even many Chinese and non-Chinese members may be unaware of their exact nature or function – and likely number over a thousand, since they are present (with some variation) in every country.8

This is a Work in Progress; it offers snapshots of what I call “China-in-Germany”, a project that needs urgently to expand across Europe as these activities are connected geographically and via persons. A group such as the Frankfurt-based Federation of Chinese Professional Associations in Europe (FCPAE, 全欧华人专业协会联合会), which is connected the United Front system, is active north into Finland, west to Ireland, and south to Portugal and Greece.10 Its logo:

There are regional variations; appeals to the ethnic and political loyalties of Chinese students in, say, Spain and Germany may be differently pitched (in Germany the message appears to be, “stick with your kind”, while in Spain it appears to be, “integrate better with locals”, though it’s not clear if this is true over time).11 To date, research of united front activities in Europe has mostly taken place in neighboring Czech Republic.12

A united front federation is born: In Germany

Just over a quarter of a century ago in 1993, a respected classical musical center in Mainz, the capital of Rhineland-Palatinate state in southwest Germany at the confluence of the Rhine and Main rivers, received an unusual query from Beijing: Would it like to host a pipa ensemble from China?13

No-one at the Villa Musica had heard of the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries (CPAFFC, 中国人民对外友好协会), the organization that reached out.14 Curious, Kurt Karst, a former state cultural official and founder of Villa Musica, agreed, thus embarking on a relationship with an integral part of the party-state’s global influencing efforts. As a recent article noted, “Friendship associations are one of the pillars of the global influence apparatus that employs united front tactics to systematically advance the Party-state’s interests abroad, invoking appealing vocabulary on ‘peace’, ‘friendship’, ‘cooperation’ and ‘cultural exchange.’”15

Parallel to that outreach from Beijing, dozens of friendship associations were forming (or reforming) in cities, towns and states after the collapse of interest and boycotts in the wake of the Tiananmen Massacre of 1989, with Germans motivated by an enduring curiosity and interest in Chinese music, philosophy, medicine and art. Today Karst is also chairman of the Gesellschaft für Deutsch-Chinesische Freundschaft Mainz-Wiesbaden (Society for German-Chinese Friendship Mainz-Wiesbaden).16

Yet the groups duplicated each other’s efforts, Karst said in a telephone interview; information wasn’t being shared, so in 2016, in a ceremony in a branch of the Villa Musica in Neuwied near Mainz, Chinese diplomats, senior CPAFFC officials and German officials launched a nationwide “Arbeitsgemeinschaft Deutscher China-Gesellschaften” (ADCG, Federation of German China Friendship Associations).17

The federation’s brief was and remains ambitious: as well as partnering directly with the CPAFFC (described as a “similar organization” to the ADCG in accounts of the group’s foundation), the federation is also a first port of call for “cross-regional, public German institutions and organizations” wishing to connect to China. The Chinese embassy in Berlin and its regional consulates is closely involved in the federation; the use of the new group to China was spelled out by Zhang Junhui 张军辉, the acting Chinese ambassador to Germany, at the launch: “Especially in the current, not always simple, political situation, the new federal association of China societies can further strengthen relations between our countries in the areas of culture and persons, but also knowledge and economy.” The website of the Gesellschaft der Chinafreunde e.V. Partnerschaftsverein Köln-Peking (Society of China Friends Partnership Cologne-Peking, set up in 2006 and today part of the ADCG network) describes the ADCG and CPAFFC as “similar organizations”, despite obvious differences in their political structure, background and status.18

Ties continued to deepen; In March 2018, on behalf of the ADCG, Karst signed a five-year, automatically renewable, formal cooperation agreement in Beijing with Li Xiaolin 李小林, party secretary and president of the CPAFFC.19 In it both sides commit to working on BRI projects and exchanging information about members’ activities, to “facilitate mutual understanding and friendship between the people of the People’s Republic of China and the Federal Republic of Germany […] especially to strengthen humanistic exchanges” (人文交流) “in culture, sport, science and education, youth, economy, media, and sister-city and province-level partnerships.”20 (In a curious public chiding, just a year after the federation was founded, in 2017, the CPAFFC criticized the Germans for not making enough of an effort to establish sister-city relationships, according to a press release: “Because the CPAFFC is responsible for partner city relationships…it hopes that the ADCG, as German partner, would make somewhat more of an effort on this topic.”21)

It’s all a long way from a classical music center in a 17th century fortress by the Rhine. Ms. Li, the daughter of Li Xiannian 李先念, a former state president and head of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (a core part of the formal United Front system), has the rank of a minister.22 Karst appears aware of the discrepancy. “Back then, I didn’t realize how high-ranking they were,” Karst said in the interview, referring to the first contact with the CPAFFC in 1993. “We didn’t realize it until we got to Beijing”, when Villa Musica reciprocated the pipa ensemble visit by sending a chamber ensemble to China, he said.

Yet Karst says he values the CPAFFC for being able to deliver. “It’s an organization one can rely on. There are so many one cannot,” he said.23 For her part, Li wrote in a congratulatory letter, “We are convinced that the Federation will draw together all the strength of Germany-China societies into a strong rope.”24

As well as scores of photographs of formal meetings between members, Chinese diplomats and German officials, the ADCG website features reports sympathetic to the party’s point of view, including on politically sensitive issues such as the trade conflict with the United States. No critical reports are available, for example on the internment camps in Xinjiang, Hong Kong democracy protests, or China’s disputed militarization of the South China Sea.

And despite the organization’s stated emphasis on culture and friendship, when the Germans, led by Karst, traveled to Beijing in March 2018 to sign the cooperation agreement, they were treated to a diet heavy in AI and hi-tech: A tour of the Artificial Intelligence Technology Center and High Technology Park in Beijing, Cross-Border E-Commerce Comprehensive Pilot Area in Hangzhou, Chinese-European Intelligent Manufacturing Park and Economic-Technological Development Area in Yiwu, and headquarters of Alibaba in Hangzhou and Tencent in Shenzhen. Karst’s biography lists nearly 30 journeys to China since 1995, for a mixture of cultural and economic-strategic events. In 2017 he attended the German-Chinese Guitar Summit in Inner Mongolia as well as the first Belt and Road Forum in Beijing. In 2019 he attended the second BRI forum.25 Karst did not respond to follow-up requests to talk about how he and other members of the federation understand its ties to the CPAFFC.

In economy, technology and politics, the ADCG also plays a significant role in furthering China’s interests. Its upcoming annual general meeting, in Duisburg in November 2019, will feature a tour of the Huawei-built “Rhine Cloud” under construction in Duisburg (a city about 250 kilometers north of Mainz on the Rhine). The project is linked to Duisburg’s “Smart City” which will give Huawei access to the city administration and aims, overall, at the “automatization” of Duisburg.26 City leaders, local businessmen and intellectuals, some from nearby universities and many the recipients of public funding, have been hosted at Huawei headquarters in Shenzhen. Yet in a meeting in Berlin, a leading German sinologist who accompanied politicians including the Mayor of Duisburg, Sören Link, to Huawei HQ, refused to share details of the visit.27

The ADCG’s links into German politics are many. Johannes Pflug, a former Social Democratic member of Germany’s parliament who worked on German and EU security, and a former chairman of the Bundestag’s German-Chinese parliamentary group, is a member of the ADCG leadership. Pflug is also “China representative” for Duisburg, home to major German industry such as Thyssen-Krupp; an honorary member of the Confucius Institute at the University of Duisburg-Essen, and recipient of the Federal Order of Merit (Germany’s only federal-level honor, is awarded by the German president; other members of the ADCG are also recipients, making them part of a social elite). Interaction with China is intense, Pflug said in a media interview: “We host regular – practically weekly – delegations”, adding, “When there’s concrete interest then we establish fast, uncomplicated connections to the required business partners, to administration and to economic facilities.”28 Pflug did not respond to emailed requests for an interview.

On its website, the federation says it aims “to build sustainable German-Chinese relationships and promote mutual understanding and respect for each other’s cultures […] working together for a stable and peaceful world order.” Laudable goals; yet it is in reality a nationwide multiplier of the CCP’s voice in Germany. This story shows how, from modest beginnings, in careful work over decades, the CCP has achieved a significant platform in the heart of German civil society that tells a CCP-approved “story” about China. Jarringly, in an article in Das Parlament, the newspaper of the German Bundestag that appeared as the Chancellor Angela Merkel was preparing to undertake her 12th official visit to China in September 2019 accompanied by a large business delegation, Karst said that his Mainz association “avoids” politics, adding there is “annoyance” among members over the “distorted” picture of China in media.29

Given the per se political nature of its partner, the CPAFFC (which is part of the party-state system), the ADCG’s extremely frequent interactions with Chinese diplomats in Germany, the absence of any counter-narrative to the CCP in its work and on its website, and the group’s commitment to support party-state projects within the framework of the BRI, that it “avoids politics” is not the case; perhaps unwittingly, it is certainly political.

“Frankfurt am Ming”

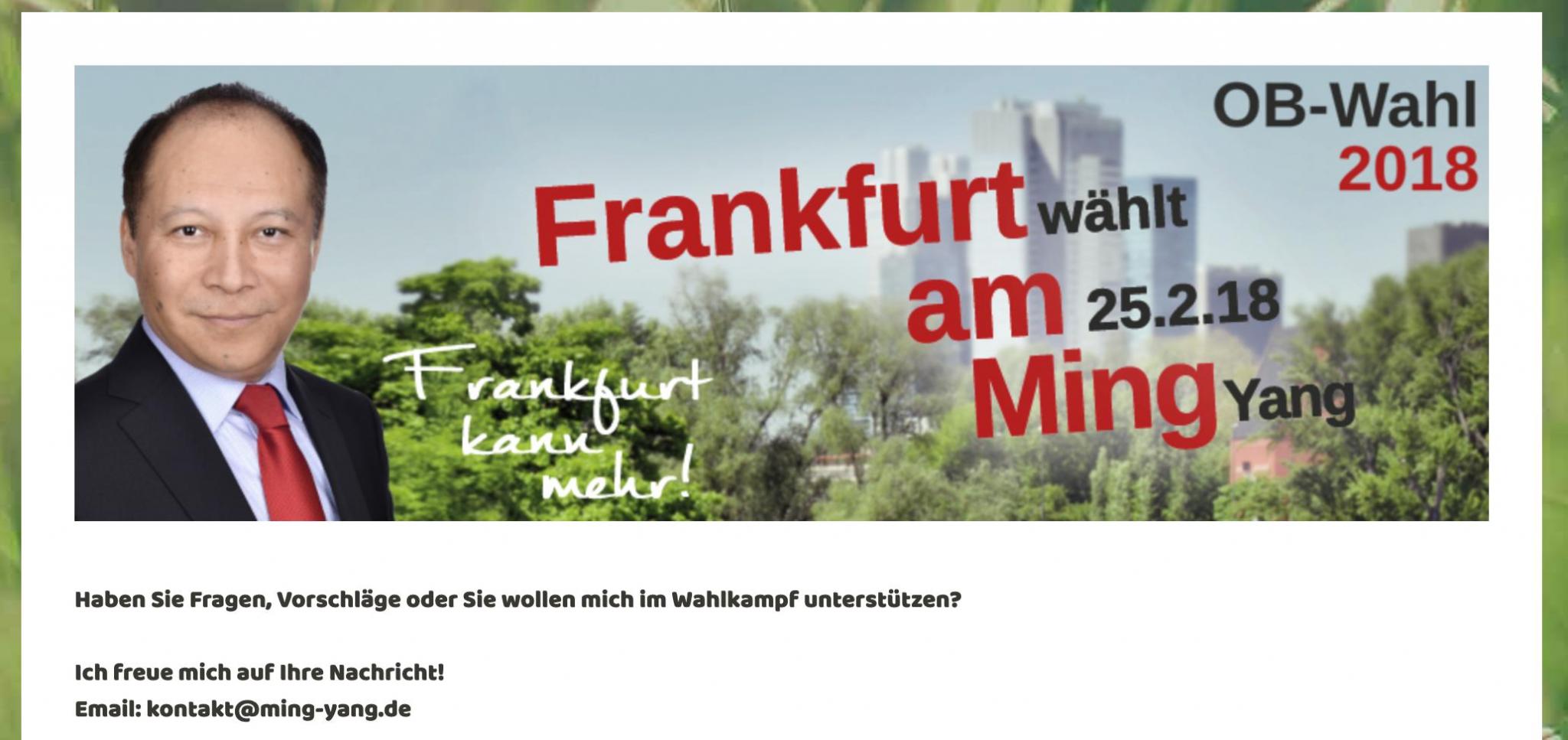

Upriver from Mainz, in Frankfurt-am-Main, the best Chongqing hotpot in Germany is to be had in the once notorious, now business-filled “Bahnhofviertel” of Germany’s financial capital which is also home to the European Central Bank, and a major center for Germany’s Chinese diaspora. Here the consultant and businessman Yang Ming 杨明, a Sichuan-born, naturalized German citizen who is an overseas member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), a United Front organization, made history in 2018 by becoming the first person of Chinese origin to stand for the position of Oberbürgermeister (Lord Mayor) in Germany.30 Yang did not win – in fact he gained just 0.5 percent of the vote.31 Yet his position as a CPPCC delegate indicates he is a person of interest to the party, as well as formally part of a United Front network. Despite losing the race for mayor, Yang is already a local politician as a member of the Foreigner’s Council (Ausländerbeirat) of the state of Hesse where Frankfurt is located, where he is one of an 18-person electoral “Chinese List.”32 Such direct involvement in democratic politics by a person who is openly politically active in China may be widespread in other countries, primarily Anglophone ones, but is quite new in Germany.

Yang wears many hats: He is head of the (United Front-linked) German Overseas Chinese Business Council (德国侨商会) and has facilitated cooperation in Germany with the BRI-linked trains that run between China and the state of North Rhine-Westphalia.33 Since 2011 he has been executive director of the “Germany-Asia Development Society” (DAG, Deutsch-Asiatische Entwicklungsgesellschaft). Despite the name, this appears to be a company specializing in the import and export of communications technology goods, publication and distribution of newspaper, road- building machines, food packaging, travel services and more, according to a declaration on the German companies register.34

For all that diversity Yang’s pitch to be Lord Mayor was focused: As well as pro-business policies, a key plank was for police officers to receive a two-year guarantee of affordable housing if they moved to Frankfurt to help improve law-and-order. His slogan: “Frankfurt kann mehr”, (Frankfurt can do more); his signature, the sinicized “Frankfurt am Ming”.35 For a politician, he appears low-key: No information is currently on his website other than a contact page. An email sent to his address on the contact page was not immediately answered (the article will be updated as necessary).36 Hessenschau.de, a major local media, reported that as a mayoral candidate he declined to take part in a video interview, despite repeated requests.37 Naturally, it is to be welcomed that new Germans become involved in democratic politics. This paper makes no allegations about Mr. Yang, but seeks to give a fuller picture of his background, including his connections to organizations that are part of the United Front system, something German media have not done.

Overall, awareness of political risk is growing among the German authorities. In its latest, 2018 report, the domestic intelligence agency, the Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz (BfV, Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution), increased its reporting on China by 6 pages compared to 4 over 2017. On the CCP’s influencing and espionage attempts, the office wrote: “It’s decisive for these strategies to create a favorable political environment. […] Chinese state, semi-state and private actors pull in well-networked German decisions makers and multipliers as ‘lobbyists’ for Chinese interests.”38

Chinese-language media in Germany

Frankfurt is also a center of Germany’s vigorous Chinese-language media. Once diverse in view, they have largely been “harmonized” and reflect party views and goals such as the BRI (with the notable exception of the German language Epoch Times, a Falungong-affiliated newspaper). These media re-publish extensively from official party and state media, including Xinhua (新华社), China News Service (中新社), People’s Daily Overseas (人民日报海外版) and Global Times (环球时报). One such, the Hamburg-based Europe Times (欧洲新报) reportedly is owned by a travel company, Caissa Touristic, which offers “excellent connections to companies, officials, ministries and associations in China” as well as touristic fun.39 Another is the Chinesische Handelszeitung (华商报).40 In Munich, a “new media”, Kaytrip (开元公司), founded by a former Chinese student in Germany in 2002, today hosts the People’s Daily Overseas (人民日报海外版). It says its main fare is aggregating “study, information, business, travel and entertainment” news, and it claims hundreds of thousands of Chinese readers in Europe.41

The author estimates there are about a dozen main media channels operating in Germany that reflect and further the CCP’s interests; Europe-wide the number may be around 100, concentrated in Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Italy and Spain, with a presence in each country. But the figure is difficult to pin down and would require far more detailed research. Reflecting European political realities, a media in France may have a German-language channel, such as the Paris-based European Times (欧洲时报, in Chinese, German, French and English), and act as an umbrella for many Europe-based Chinese-language media.42

Founded in 1983, the European Times claims to have branches in six European countries (including Russia), and two dozen online or social media accounts throughout Europe.

In an interview, a Hong Kong journalist who worked for a pro-CCP newspaper in Hong Kong and the mainland of China until 1989, when they resigned in protest at the military suppression of the Tiananmen Square democracy movement, recounted how during an overseas study leave in Europe in 1980 they were contacted by a member of the cultural section of the Chinese embassy in Paris to establish the European Times. They turned the offer down in order to return to China, but said it proved that the Chinese embassy was instrumental in setting up the newspaper.43 Reportedly part of Guang Hua Cultures et Media (in Chinese on its website, oushinet.com, the name is given as ‘European Times Media Group’ (欧洲时报传媒集团)), this is a large and diversified group that claims to run travel and education businesses, among other things.44 The European Times co-organizes regular events for Chinese-language media across Europe attended by local Chinese embassy officials, senior Europe and China-based employees of the China News Service (中新社), and local European media and officials, such as in Florence in Italy in May of this year, where the consul-general there, Wang Wengang 王文刚, was present.45 Reflecting its key role in marshaling Europe-based Chinese-language media that is guided by the party, in 1997 it founded the European Chinese Media Association (欧洲华文传媒协会), reportedly in response to “strong demand from Chinese language media in Europe to make it easier for everyone to unite and discuss common issues and strengthen cooperation.”46

At one typical, Europe-wide event organized by the media association, more than 40 Chinese-language media from 18 European countries gathered in Prague in 2018 for an event co-organized by the Czech Council for the Promotion of the Peaceful Reunification of China, one of many European branches of a key body that draws together United Front organizations overseas.47

Another event gathering Europe-wide Chinese-language media, this one in China, is the Global Chinese Language Media Forum (世界华文传媒论坛), co-organized by the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office and local government and party branches.48 Under the motto “friendship, exchange, study and discuss, develop” it aims “to promote communication and cooperation amongst overseas Chinese media and with Chinese media” by inviting several hundred media from inside and outside China.

At its most recent meeting in Lijiang, Yunnan province in July 2019, the director of the People’s Daily Overseas Edition Online Data Research Center (人民日报海外网数据研究中心), Lu Yongchun 卢永春, presented a study assessing the influence of 400 overseas Chinese-language media.49 Two European-based new media were among the “Top 20” influencers: Germany’s www.dolc.de (德国热线)50 and France’s Xineurope.com (新欧洲).51 Xineurope is reportedly owned by E.Can Inc. (易能传媒), with seven subsidiary sites. Its homepage links to the education section of the Chinese embassy in Paris which offers free subscriptions of the People’s Daily Overseas edition for Chinese state-funded students, teachers, members of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Confucius Institutes, and student, professional and alumnus associations in France, “in order to understand what is happening at home.”52

A third event regularly attended by Europe-based overseas Chinese media, this one also held in China, is the Overseas Chinese New Media Forum (海外华文新媒体高峰论坛).53 At a meeting of this forum in Hangzhou in 2018, Tan Tianxing 谭天星, a deputy minister of the United Front Work Department, told delegates that major administrative changes in March 2018 that gave the United Front institutional control over the State Council’s overseas Chinese system would only intensify the United Front’s commitment to overseas Chinese media.54

Conclusions

Germany and China like to say their relationship is broad and deep, and that is no exaggeration, as trade figures and regular bilateral cabinet meetings show.55 A cognitive and political shift is required in Europe to recognize Chinese influencing, how it is shaping the lives and opportunities of Chinese living in Europe, and the narrative about China in European society more broadly. While not everyone involved in these united front systems is clear about their role or the aim of the organisations, the consequences are real and include facilitating technology transfer (whether legal, semi-legal or outright illegal), and economic and other espionage. Berlin, including the federal Justice Ministry, remains timid about drawing public attention to problems such as this widespread, questionable technology transfer or other issues. A recent, high-profile case in Cologne in 2018 that reportedly bore the hallmarks of Chinese state involvement has so far not been prosecuted as espionage but only as “unfair competition”, to the apparent disappointment of the BfV.56

German sinologists, who have access to the language, must take part of the blame for this lack of awareness, though in this they are not alone in Europe. Sinologists have looked away from the realities of CCP power, even from how the party frames their own research, as Andreas Fulda of the University of Nottingham pointed out recently.57 China, the conventional argument goes, is “different”, something I have argued against, dubbing this view “Late Orientalism.”58 One could perhaps go further and call it “Neo Orientalism” for how it underestimates China, the CCP’s will to power, and how China could change our world under the CCP. There are notable exceptions, such as Heiner Roetz of the Ruhr-Universität Bochum, who wrote, perceptively, in 2016: “Western sinology seems to be on the wrong side in the conflict between the government and its opponents. This does not necessarily mean that the sympathies of sinologists are with the dictatorial regime and not its victims. But they tend to treat the latter with a kind of benevolent incomprehension.”59

Traditional anti-Americanism in Germany has been sharply exacerbated by widespread opposition to Trump’s illiberal policies and rhetoric, strengthening the also widespread binary (America Bad / China Good) logic that the CCP benefits from. One survey in February found about 40 percent trusted China as a partner while only about 20 percent trusted the U.S.60 China is aware of this and trying to use Germany as a lever against the U.S., as the Sino-US trade conflict deepens.61

Recommendations

These examples are all threads that, when pulled, begin to unravel a hitherto-unreported, rich tapestry of influencing. The German government should urgently make available more funding to construct a full picture of it. Innocent activities must be shielded from prejudice; but deliberate influencing conducted in an orchestrated manner cannot be ignored. The German government needs to urgently debate, and bring in, FARA-style legislation. Currently united front activities are taking place under the guise of social, “non-political”, even charitable organizations (this language is frequently written into organizational charters)62 but, where there are documented, regular, direct ties to the United Front, the ties these actors and organizations have to the CCP should be identified accordingly.

Didi Kirsten Tatlow is a journalist and independent researcher based in Berlin.

Sinopsis is a collaborative project between the Institute of East Asian Studies at Charles University in Prague and the non-profit AcaMedia Institute. The Oriental Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences (CAS), a public research institution, co-organised the 2019 Sinopsis workshop with financial support from CAS Strategy AV21.

-

Florian Wilde, Revolution als Realpolitik. Ernst Meyer (1887-1930) – Biographie eines KPD-Vorsitzenden (UVK Verlagsgesellschaft, 2018).↩︎

-

“习三不痛批吃饱了没事干的外国人,” CCTV, February 11, 2009; Chris Buckley and Sui-Lee Wee, “China heir apparent Xi raised by elite, steeled by turmoil”, Reuters, August 19, 2011; “习近平痛批少数外国人对中国事务指手画脚,” 人民网, February 13, 2009.↩︎

-

Pan Yue 潘岳, Party Secretary of the Central Institute of Socialism (“统一战线是马克思主义中国化的重要理论实践成果,” 中央社会主义学院, July 2019.).↩︎

-

Xi Jinping speech, 2015: “Consolidate and develop the broadest patriotic united front in order to […] realize the China Dream of the rejuvenation of the Chinese people” (“习近平:巩固发展最广泛的爱国统一战线,” 新华网, May 20, 2015.).↩︎

-

“China-EU – International trade in goods statistics,” Eurostat, 2019.↩︎

-

For a recent use of the term 统战性, see “龙岩市湖北商会成立,” 龙岩市委统战部, September 25, 2019.↩︎

-

The figures are a baseline, and the first attempt that I am aware of to put a number on the real scale of united front work in Germany. It errs on the conservative side. The number includes formal United Front-affiliated groups (more than 190) and the 37-strong “Arbeitsgemeinschaft Deutscher-China Gesellschaften” (ADCG), which partners with the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries, the CPAFFC. The 190-plus number was arrived at by linking these groups (e.g. via Chinese language media reports) to organizations of the CCP United Front system including the Chinese Overseas Exchange Association (中国海外交流协会) and the China Overseas Friendship Association (中华海外联谊会). The ADCG was added to the 190-plus figure to give a better impression of scale, because though the CPAFFC is not formally part of the United Front system it does significant united front-style (统战性) work. Other groups (student and professional associations, media, and so on) cooperate to varying degrees, and with varying levels of awareness among the people involved. Thanks to Peter Mattis for research and subsequent conversations.↩︎

-

Good figures on the actual size of Germany’s Chinese population are hard to come by due to concern over privacy issues and how to count “foreigners”. Official statistics give 143,135 people as of 31 Dec ’18: Ausländische Bevölkerung. Ergebnisse des Ausländerzentralregister 2018 (Statistisches Budesamt (Destatis), 2019).↩︎

-

For the 2015 meeting, see “德国华助中心会长联席会议取得圆满成功,” Kaiyuan, June 18, 2015. The website of the Frankfurt-based Chinesische Handelszeitung says it is “politisch neutral, überparteilich und wirtschaftlich unabhängig” (“politically neutral, non-partisan and economically independent”.) For the report on how the Chinese Aid Centers work with the consulates, see “全德华人社团联合会迎春团拜 孙瑞英副总领事和上百同胞出席,” 华商报 / Chinesische Handelszeitung, March 9, 2016.↩︎

-

“2018年度全西学联大会在萨拉曼卡成功召开,” 神州学人, October 15, 2018.↩︎

-

Telephone interview with Kurt Karst, a former head of the Villa Musica and current head of the Gesellschaft für Deutsch-Chinesische Freundschaft (GDCF) Ortsverein Mainz-Wiesbaden. See: Gesellschaft für Deutsch-Chinesische Freundschaft Mainz-Wiesbaden. Karst is also head of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Deutscher-China Gesellschaften, see “Kurt Karst,” Arbeitsgemeinschaft Deutscher China-Gesellschaften e.V. The interview was conducted in April 2019. See also Villa Musica.↩︎

-

Interview with Karst, see previous note. For CPAFFC, see its website.↩︎

-

Olga Lomová, Jichang Lulu, and Martin Hála, “Bilateral dialogue with the PRC at both ends: Czech-Chinese ‘friendship’ extends to social credit,” Sinopsis, July 28, 2019.↩︎

-

See above, and “Gesellschaft für Deutsch-Chinesische Freundschaft (GDCF) Ortsverein Mainz-Wiesbaden,” mainz.de. Originally founded in 1978, according to a recent article in Das Parlament, the newspaper of the German Bundestag, the Mainz association had “fallen somewhat asleep in 1989” for reasons that are not explained but “got a fresh wind” in 2014 (Lisa Brüßler, “Auf einen Tee mit den Meenzer China-Freunden,” Das Parlament, August 12, 2019).↩︎

-

“Kurt Karst”; “ADCG-Präsidium besucht CPAFFC in Beijing,” ADGC, March 2017.↩︎

-

“Gründung der Arbeitsgemeinschaft Deutscher China-Gesellschaften (ADCG),” Gesellschaft der Chinafreunde – Partnerschaftsverein Köln Peking, December 5, 2016.↩︎

-

For the cooperation agreement in German and Chinese: “Kooperationsvereinbarung zwischen der Gesellschaft des chinesischen Volkes für Freundschaft mit dem Ausland (CPAFFC) und der Arbeitsgemeinschaft Deutscher China-Gesellschaften e.V. (ADCG) / 中国人民对外友好协会与德国德中友好协会联合会合作协议,” ADCG, March 22, 2018.↩︎

-

“Humanistic exchange” (人文交流), carries a particular meaning in CCP parlance. See, for example, 许利平,王晓玲, “深化人文交流 共建文明之路,” 经济日报, August 18, 2017. This term refers to perceived “economic inequalities and cultural differences” along the Belt and Road, whereby the BRI can only truly succeed by building a complementary “Civilization Road” (文明之路). “This is not only helpful in furthering the great rejuvenation of the Chinese people […] it is even more helpful in realizing the goal of a ‘common destiny of mankind’”. For a sense of the scale of the enterprise, see the Ministry of Education’s “China Center for International People-to-People Exchanges” (教育部中外人文交流中心).↩︎

-

See Wang Xinhua, “Daughter of Li Xiannian: We Did Not Do Business, as Father Said,” Xinhua, March 17, 2014. For more on Li’s background and political connections, including her father Li Xiannian and her husband Liu Yazhou 刘亚洲: “李先念同志生平,” 中国共产党新闻网, and “刘亚洲上将:我空军再次面临紧急关头,” 中国军网, June 6, 2014.↩︎

-

Interview with Karst.↩︎

-

See, “Gratulationsschreiben”, in “Kooperationspartner: The Chinese People‘s Association for Friendship with Foreigb [Sic] Countries (Cpaffc),” ADGC.↩︎

-

Numerous articles and images on the ADCG website.↩︎

-

Achim Sawall, “Duisburg und Huawei starten die Rhine Cloud,” Golem.de, June 11, 2018.↩︎

-

Berlin, September 2018. The source cannot be named due to the Chatham House rule.↩︎

-

On Pflug, “Johannes Pflug (MdB a.D), Duisburg,” ADGC. See also “Johannes Pflug wird China-Beauftragter der Stadt,” Duisburg.de, and “Neue Herausforderungen und Chancen durch das Seidenstrassen-Projekt,” Stadtmacher China-Deutschland, April 2018.↩︎

-

For Yang’s candidacy, see Martina Schumacher, “Ming Yang kandidiert als Oberbürgermeister: ‘Frankfurt kann Mehr’,” Journal Frankfurt, January 15, 2018. For his status as an overseas CPPCC member, see “全国政协海外特邀委员约莫史波(杨明):融入德国主流社会,讲好‘中国故事’,” 环球网, March 2, 2019.↩︎

-

“Ming Yang”; “Chinesische Liste.”↩︎

-

For Yang’s many positions, including the German Overseas Chinese Business Council, see “德媒:杨明有望成法兰克福市长 开创华人参政先河,” 环球时报, December 25, 2017. For his involvement in the trains, sometimes represented as “the European end of the Silk Road”, see “全国政协海外特邀委员约莫史波(杨明):融入德国主流社会,讲好‘中国故事’.”.↩︎

-

For the activities of the DAG, Deutsch-Asiatische Entwicklungsgesellschaft, see Öffentliche Bekanntmachung (Amtsgericht Frankfurt am Main Aktenzeichen: HRB 58652), 24 October 2011, accessed via Gemeinsames Portal der Länder: „Import und Export von Waren der Kommunikationstechnik, die Herausgabe und der Vertrieb von Zeitungen, kunstgewerblichen Gegenständen, Baustoffen, Maschinen (insbesondere Straßenbaumaschinen) sowie von verpackten Nahrungsmitteln, Tabak, Drogerieartikeln und pharmazeutischen Erzeugnissen. […] Zum Gegenstand des Unternehmens gehören ferner Dienstleistungen, insbesondere Reiseservice im In- und Ausland sowie Investitions- und Businessberatung zur Durchführung von Investitions- und anderen Programmen im In- und Ausland.“↩︎

-

“Yang Ming als Kandidat für die Oberbürgermeisterwahl in Frankfurt,” de.china-info24.com, January 11, 2018.↩︎

-

“Ming Yang (unabhängig),” Hessenschau, February 5, 2018.↩︎

-

Verfassungsschutzbericht 2018 (Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat, 2019), 296. The number of pages for Russia approximately doubled.↩︎

-

See “欧洲新报,” Hamburg Summit;, “欧洲新报,” March 21, 2018. Unfortunately, as of the time of writing, the website of the Europe Times (www.xinbao.de) appeared to be inaccessible. Archived versions show it was active as late as October 2016. Caissa Touristic, said to be the owner of the European Times, does not declare ownership on its company records. To search those: Gemeinsames Portal der Länder.↩︎

-

“人民日报海外网德国频道上线仪式暨开元集团年会在德国慕尼黑举行,” “《人民日报》海外网与开元网共建德国频道,” Kaytrip.↩︎

-

Author’s count. Figure based on multiple online Chinese-language media and company descriptions, including lists of Europe-based Chinese media regularly attending meetings with United Front-linked organizations. See, for example, “第九届世界华文传媒论坛欧洲参会名单,” 中国侨网, September 6, 2017.↩︎

-

Personal interview in Hong Kong, September 2019. The journalist’s name and other relevant details are withheld to protect them but are known to the author.↩︎

-

“2019欧洲华文新媒体论坛在意大利成功召开,” 旅罗华人报, May 30, 2019; “欧洲华文媒体负责人汇聚‘ 2019年欧洲 华文新媒体论坛’报到现场,” Ifeng.com, May 28, 2019.↩︎

-

“数十家海外华文媒体齐聚意大利 共探数据时代发展之路,” 欧洲时报, June 13, 2019.↩︎

-

See “欧洲华文传媒协会2018第十三届年会定于7月在捷克首都布拉格举行,” 布拉格时报, June 29, 2018. For the CPRRC, see, for example, the German council: 德国华人华侨中国和平统一促进会.↩︎

-

“第十届世界华文传媒论坛征集论文,” 中国新闻网, March 29, 2019.↩︎

-

“《2019海外华文新媒体影响力报告》发布,” 海外网, July 9, 2019.↩︎

-

“易能传媒,” xineurope.com; “《人民日报海外版》订阅,” 中华人民共和国驻法兰西共和国大使馆教育处, January 29, 2017.↩︎

-

“海外华文媒体赴普洱采风:在这里,心情总如歌声般轻快,” 海外网.↩︎

-

“谭天星谈海外华文媒体使命担当 提四点希望,” 中国新闻网, May 29, 2018.↩︎

-

See “Responsible partners for a better world,” Auswärtiges Amt, July 11, 2018. Germany and China’s full cabinets, including the leaders of government (recently Angela Merkel and Li Keqiang) have met every two years since 2011 in a unique show of political friendship.↩︎

-

Andreas Fulda, “Wie die Kommunistische Partei die Wissenschaft gefährdet,” Zentrum Liberale Moderne, June 12, 2019.↩︎

-

Didi Kirsten Tatlow, “Cultural Relativism and Power Blindness: Some critical observations on the state of Germany’s China debate,” Zentrum Liberale Moderne, November 22, 2018.↩︎

-

Heiner Roetz, “Who is Engaged in the ‘Complicity of Power’? On the Difficulties Sinology Has with Dissent and Transcendence”, in: Nahum Brown and William Franke (eds.), Transcendence, Immanence, and Intercultural Philosophy, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016. German original: “Die Chinawissenschaften und die chinesischen Dissidenten. Wer betreibt die ‘Komplizenschaft mit der Macht’?↩︎

-

Richard Connor, “Germans trust China more than the US, survey finds,” Deutsche Welle, February 8, 2019.↩︎

-

Private conversations with diplomats.↩︎

-

See, for example: “全欧华人专业协会联合会章程,” FCPAE, November 22, 2003. This organization’s charter states that it is “independent of any party” (联合会独立于任何党派,在政治和宗教方面保持中立). This is highly unlikely given it hosts and cooperates with members of United Front organizations. While the author is aware that the statement is angled toward Europe and the intention is likely to state that organizations claiming this are independent of European political parties in line with their registered status, the point that they are not in fact politically independent remains and should be of concern to the authorities.↩︎