This article is also available for download.

- Human rights and civil society — essential for the success of the 2030 Agenda

- The PRC’s view: Right to (state-led) development is sufficient to achieve the SDGs

- China (and friends) promote alignment of the BRI with the 2030 Agenda

- Belt and Road corruption and China’s “stability” imperative could sabotage the SDGs and “leave many people behind”

During the past several years, the PRC has aggressively promoted its view that the “right to development” transcends all other rights, while at the same time selling its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as the answer to the UN’s ambitious and cash-strapped 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.1 With the assistance of PRC nationals working at the UN, Chinese Communist Party-linked “NGOs” with consultative status at the UN, bribery, influence, and more,2 China made substantial headway convincing key UN officials and a number of diplomats that the BRI was closely aligned with the 2030 Agenda, and that their “synergies” charted a path forward to achieving the 2030 Agenda’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).3 Recently, however, the BRI has encountered pushback, not just in some of the countries along the Belt and Road whose troubles have been covered widely in the international media, but also at the UN.4

The Chinese government would prefer to keep human rights off the Belt and Road and out of discussions about the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs. Recently, however the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) has taken concrete steps to operationalize the widely held view that the 2030 Agenda can only be achieved through a human rights-based approach, which takes into account all human rights. A growing focus on the inextricable linkages between the SDGs and human rights not only runs counter to China’s “development first” theory of human rights, but also raises questions about the PRC’s ongoing efforts to cast the BRI as synergistic with the 2030 Agenda.5 The PRC’s conduct at the UN, particularly in the Human Rights Council and the UN NGO Committee, demonstrates its contempt for civil and political rights, civil society, NGOs, and human rights defenders at the international level. The Chinese Party-state’s human rights record domestically is abysmal and getting worse.6 As an extension of the totalitarian Party-state, the BRI cannot seriously be considered a vehicle for enabling human rights progress and civic space around the globe.7 Rampant corruption, and lack of transparency and accountability along the Belt and Road also pose significant obstacles to the SDGs. The PRC, its BRI, and its vague vision of a “community with a shared future for humankind”8 threaten to undermine the realization of the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs, and the pledge all countries undertook with the adoption of the 2030 Agenda: “to leave no one behind.”

Human rights and civil society — essential for the success of the 2030 Agenda

Unanimously adopted by the UN General Assembly in September 2015, the 2030 Agenda and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (encompassing 169 targets) is an ambitious comprehensive framework for post-2015 global development.9 The Agenda aims to achieve a wide range of social, economic, justice, governance, and environmental development goals, captured by the “five Ps” —-people, planet, prosperity, peace and partnership.10 Despite China’s involvement in the drafting of the 2030 Agenda and its work to ensure that certain human rights were not expressly included in the text, human rights are nevertheless fundamental to the 2030 Agenda, which is “grounded in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights” and international human rights treaties (para.10). In adopting the Agenda, States “envisage a world of universal respect for human rights and human dignity, the rule of law, justice, equality and non-discrimination,” as well as a “just, equitable, tolerant, open and socially inclusive world in which the needs of the most vulnerable are met” (para. 8).11

The SDGs expand upon the previous Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and seek to complete the MDGs “unfinished business,” particularly with respect to “reaching the most vulnerable” and marginalized members of society.12 Accordingly, the 2030 Agenda emphasizes the principles of equality and nondiscrimination, and the linkages between the SDGs and human rights.13 Indeed, the Agenda states that the SDGs “seek to realize the human rights of all.” While the MDGs applied only to developing countries and had a somewhat narrow scope,14 the Sustainable Development Goals are universal, comprehensive, transformative, and inclusive;15 indeed, they are also known as the Global Goals.16 The SDGs include, for example, zero poverty and hunger, gender equality, clean water, good health and well-being, climate action, reduced economic and other inequalities, and peace, justice, and strong institutions.

The linkages between the SDGs and human rights were the focus of a January 2019 Intersessional Meeting of the Human Rights Council, “Human Rights and the 2030 Agenda: Empowering people and ensuring inclusiveness and equality.”17 In his concluding remarks at the gathering, the rapporteur for the event, Michael O’Flaherty, director of the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, said that his “two or three line takeaway from the entire day is that if we don’t succeed in delivering the SDGs with human rights embedded within them, then the whole SDG project will fail.”18

The summary report (A/HRC/40/34) of the meeting also noted the “widespread sense that the SDGs could only be realized through a human rights-based approach to their implementation at the local, national, regional and global levels” (para. 90). Moreover, the report reflected the participants’ shared view that civil society’s involvement was critical to the success of the 2030 Agenda. Accordingly, “civic space must be protected” and “civil society must enjoy freedom of expression, assembly and association” in order for it to be able “to make its essential contribution” to the implementation and achievement of the SDGs (para. 96).19

The 2030 Agenda also reflects lessons learned from the MDGs’ process, including the importance of “more transparent, accountable and inclusive approaches to development”20 and the necessity of civil society involvement.21 Many stakeholders, including UN Secretary-General António Guterres, other UN officials, diplomats, civil society organizations,22 think tanks,23 and international development experts have expressed the view that civil society has a key role to play in the implementation of the SDGs, and in the follow-up review and monitoring of how countries are progressing towards those goals.24 The mobilization of civil society for the 2030 Agenda and the increased interest of civil society organizations in contributing to the work of the UN is evident in the dramatic rise of the number of organizations applying for consultative status with the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) —- from 440 applications in 2014 to 820 applications in 2019.25

The PRC’s view: Right to (state-led) development is sufficient to achieve the SDGs

The CCP, however, has a very different view of the relationship between development and human rights, and of the role of civil society both in development and in the defense and promotion of human rights. Since the PRC first began engaging in human-rights discourse and diplomacy, it has prioritized the right to development and the right to subsistence above all other rights.26 Despite its agreement with consensus language in many international human rights instruments containing the fundamental principle, as spelled out in the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action (para. 5), that “all human rights are universal, indivisible and interdependent and interrelated,” the PRC nonetheless persists in treating the right to development as the “first right,” without which, according to its view, other human rights would be impossible to achieve.27 And for the PRC party-state, development is a top-down endeavor , with no space for civil society input and monitoring.28

In its 1991 inaugural white paper on human rights , a post-Tiananmen effort to defend itself against censure and sanctions from Western governments and in UN fora, the PRC extolled the right to subsistence as the fundamental right, so foundational that other rights couldn’t even be discussed without it (“人权首先是人民的生存。 没有生存权,其他一切人权均无从谈起。” ).29 It argued that because “social turmoil” (动乱) —one of the terms used by the party-state for the 1989 Tiananmen protests—- threatened this foundational right, maintaining “stability” ( 稳定 ) remained an “urgent task” of the Chinese government. The 1991 white paper also heralded the importance of the right to development for developing countries, including China, and stated that this, too, was a priority right.

China’s aggressive promotion of its theory of “human rights with Chinese characteristics”30 and governance—- highlighting the primacy of the rights to development and subsistence and positioning itself as a leader in “global human rights governance”—- was front and center during China’s Universal Periodic Review (UPR) at the Human Rights Council in November 2018.31 The following month, the State Council Information Office issued a white paper titled “Progress in Human Rights over the 40 Years of Reform and Opening Up in China,”32 which expounded on its theory claiming that “the rights to subsistence and development are the primary rights – the preconditions and the foundation for all other human rights.”33 Echoing this view, the PRC Ambassador to South Africa, Lin Songtian 林松添, made the case for China’s global leadership and its “human rights model” in a January 2019 op-ed for the South African media outlet Independent Online. In his piece titled “China is setting up a new model for world human rights,” Ambassador Lin wrote: “We believe that development is the fundamental solution to improving human rights.”34 A Chinese version of his op-ed (“中国为世界人权事业树立了新典范”) appeared domestically in state media.35

Although Chinese officials give an occasional rhetorical nod to the universality of human rights, such statements are usually immediately negated by a stress on “national conditions” and the absence of one single path for achieving human rights.

An example of this formulation was evident in a congratulatory letter Xi Jinping sent to a conference held in Beijing on the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).36 The letter stated that the greatest human right was the people’s well-being (幸福生活) and that China persists in combining the principle of the universality of human rights with the reality of contemporary times, and that it follows a human rights development path that suits its national conditions.

Depending on changing “national conditions” in China (as defined by the party-state) or international developments, the CCP may invoke other political urgencies as “the greatest” human right. For example, with increased international attention on the mass internment of untold numbers of Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslim minorities in Xinjiang,37 the CCP’s Global Times published an editorial in August 2018 condemning the criticism and proclaiming “peace and stability” in Xinjiang as “the greatest human right.”38 And during a general debate on human rights at a meeting of the UN’s Third Committee in October 2018, Ambassador Wu Haitao 吴海涛 stated that “security is the most paramount human right.”39

The PRC’s “new model for world human rights” excludes individuals and civil society actors as rights holders and participants in the defense and promotion of human rights.40 The assault on civil society in Xi Jinping’s New Era has been well documented by journalists, human rights organizations, and civil society actors.41 It’s a bleak picture.42 In its 2018 annual report , the NGO Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD) observed that Xi Jinping and his government “escalated brutal suppression of rights activists, lawyers, critics of authoritarian rule” and others.43 Human Rights Watch,44 CHRD,45 and the UN Secretary-General’s report on reprisals (A/HRC/39/41, re China, paras. 9-17)46 have also shown how the PRC party-state threatens, intimidates, and punishes its citizens who seek to engage with the UN human rights mechanisms.

While UN Secretary-General António Guterres has described human rights defenders (HRDs) as “essential partners to governments and to the United Nations in tackling the enormous challenges we face globally in fully implementing the 2030 Agenda,”47 the PRC party-state spares no effort in attacking human rights defenders at home and at the UN.48 It uses vague crimes in the PRC Criminal Law , such as “inciting subversion” (art. 105 “煽动颠覆国家政权”) and “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” (art. 293 “寻衅滋事”) to criminalize HRDs’ peaceful conduct and expression domestically, and labels HRDs as “criminals” engaged in “illegal conduct” in its statements at the UN.49

China (and friends) promote alignment of the BRI with the 2030 Agenda

As Sinopsis and Jichang Lulu explained in their June 2018 article on CCP influence operations targeting the UN, the PRC has used a combination of tactics —- including discourse engineering, political and economic influence, and bribery —-to position its Belt and Road Initiative as the panacea to many of the challenges faced by the 2030 Agenda, with the ultimate aim of obtaining the UN’s imprimatur for Xi Jinping’s global foreign policy strategy and vision.50

Over the past few years, PRC officials and allies at the UN have promoted the purported synergies between the BRI and sustainable development generally, and after 2015, the 2030 Agenda specifically, often using Xiist tropes such as “win-win cooperation” and “community of shared future for humankind” (人类命运共同体). In June 2018, the PRC’s ambassador to the UN, Ma Zhaoxu 马朝旭, co-hosted a high-level forum on the BRI and the 2030 Agenda, during which he said: “The BRI and the 2030 Agenda resonate with and reinforce each other. Together, they promote the cause of international cooperation for development.” Ambassador Ma made no mention of civil society or human rights, except for the right to development, suggesting that it was the only right that really mattered to the 2030 Agenda: “The BRI is aligned with the 2030 Agenda, which emphasizes voluntarism and respect for countries’ sovereignty and right of development.”51

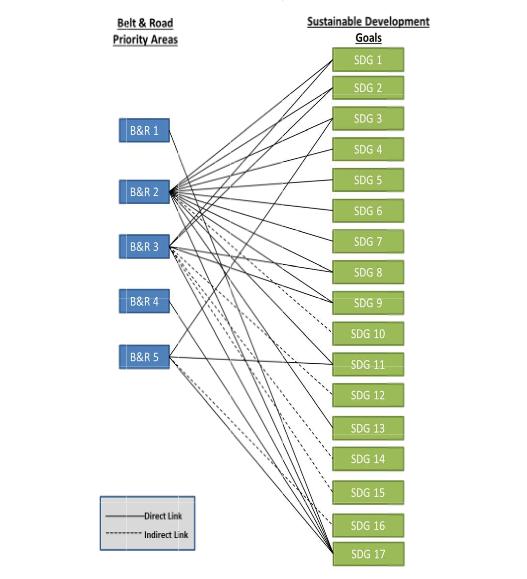

A month later in Beijing, the UN Under-Secretary-General in charge of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), former PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs official Liu Zhenmin 刘振民, said in a speech at the Belt and Road Legal Cooperation Forum, “the Belt and Road Initiative serves the exact purpose of the UN Charter through its objectives of promoting shared development and prosperity, peace and cooperation, openness and inclusiveness, and mutual understanding and trust. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development… provides a broad scope for the growth of the Belt and Road Initiative, and for the UN system to be closely engaged with the Initiative.” Liu went on to say that the “five types of connectivity” —- priorities of the BRI—- “are intrinsically linked and can effectively advance the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals.”53 Like Ambassador Ma, USG Liu failed to mention human rights or civil society (except for a brief reference to the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, encouraging businesses on the Belt and Road to observe them in furtherance of “their long-term profits.” The BRI’s “people to people connectivity” (or bonds)54 alluded to by Liu has very little to do with civil society, but rather is CCP driven, and limited to CCP-approved people and organizations, participating in CCP-approved programs, such as cultural exchanges and tourism development,55 Confucius Institutes,56 and GONGO charity efforts.57

China drafted other officials and relevant departments at the UN into the BRI bandwagon campaign. Most important, Secretary-General António Guterres has promoted the connection between the BRI and the 2030 Agenda, but similarly without mentioning the linkages between the SDGs and human rights.58 Under then administrator Helen Clark, the UN Development Programme (UNDP) entered into the first MOU with China regarding cooperation on the BRI in the fall of 2016.59 Likewise, in May 2017, the head of the UN Environment Programme at the time, Erik Solheim, praised the BRI in an op-ed for the China Daily, noting that UNEP had signed an agreement with the PRC’s Ministry of Environmental Protection “to promote sustainable development of the Belt and Road.”60 This cozy relationship would soon come to an end, however. In November 2018, The Guardian reported that Solheim was asked to resign his position amid an internal UN audit that pointed to financial and organizational mismanagement and other improprieties in violation of UN internal rules. The article also mentioned that “numerous staff” of UNEP “contacted the Guardian criticising Solheim’s perceived closeness to China” and the BRI project he initiated.61 A former UNEP staffer wrote in a blog post that Solheim’s “support of China’s Belt and Road initiative … seemed so uncritical that it set alarm bells ringing in other capitals around the world.”62

Furthermore, the PRC has actively used the UN NGO Committee’s ECOSOC consultative status procedure to facilitate the involvement of CCP-linked “NGOs” (i.e., GONGOs or “government-organized NGOs”) in its work at the UN, including in its push to enmesh the BRI in the UN. Chinese GONGOs are a significant avenue of CCP influence at the UN, a fact clearly illustrated by the case of Patrick Ho (何志平) and his “NGO” China Energy Fund Committee (CEFC). Ho used the CEFC, which obtained special consultative status in 2011, to promote “synergies” between the BRI and the UN’s sustainable development agenda, and he also used CEFC as a platform for bribing UN officials.63 In December 2018, a federal jury in New York City convicted Ho on seven counts of international money laundering and violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act for bribes instigated through the CEFC (the “NGO”) to further the business interests of CEFC China Energy Company, Ltd. in connection with China’s BRI.64 In January 2019, US diplomats led a successful effort in the UN NGO Committee to have CEFC’s consultative status withdrawn (the decision awaits ECOSOC’s final approval when it meets this summer).65

China has sought special consultative status for the Silk Road Chamber of International Commerce, Ltd. (SRCIC, 丝绸之路国际总商会), a GONGO that describes itself as a “key voice in the promotion of Belt and Road construction.”66 SRCIC has signed “strategic cooperation agreements” with among others, the government of Georgia, and has met with more than 20 leaders of “Silk Road” countries. SRCIC’s partners include, for example, the official China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT, 中国国际贸易促进委员会),67 and the official China Belt and Road Portal).68 During the January 2019 meeting of the NGO Committee, the US delegation asked SRCIC for more details about its partnerships, thereby causing a postponement69 of the Committee’s consideration of SRCIC’s application.

SRCIC chairman Lü Jianzhong 吕建中 has long held political appointments that belie the organization’s attempts to appear “non-governmental.” Besides his vice chairmanship at a CCPIT-linked organization,70 he also holds a seat on the current National People’s Congress, and earlier, he served three terms as a delegate to the national Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference.71 State media has carried Lü’s explanation of SCRIC’s role in the promotion of BRI: “the realization of the ‘Belt and Road’ vision requires cooperation at the country and government levels as well as a response from the people at the society and non-governmental levels.”72

SRCIC is most certainly not an NGO, but another potential vehicle of CCP influence at the UN.

The seemingly unquestioning celebration of the BRI by some UN officials and diplomats has become somewhat muted recently in the wake of Patrick Ho’s conviction and ongoing revelations of problems along the Belt and Road, but also perhaps reflects a general dialing down of official BRI hype and internationally73 (though this may pick up again as the Second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation nears in April).74

Belt and Road corruption and China’s “stability” imperative could sabotage the SDGs and “leave many people behind”

Hardly a week goes by without a report of a Belt and Road problem, from debt traps,75 to the likely expansion of the drug trade in Myanmar’s Shan State via the BRI’s China-Myanmar Economic Corridor,76 to the potentially catastrophic implications China’s focus on coal-fired power plants along the Belt and Road will have on climate change.77 The primary story line, however, and what connects most of the troubles facing the BRI, is corruption.78 Chang Ping 长平, a Chinese media veteran and public affairs commentator living in exile in Germany, wrote in 2017 that the “lack of democratic supervision of ‘One Belt, One Road’ is a mechanism for corruption. As with all large projects in China, there is no restriction on power, and this inevitably results in the criminal activities of corruption, rent-seeking, giving and taking bribes and money laundering.”79

Indeed, from the Belt and Road bribery of African officials at the UN revealed in Patrick Ho’s case to the 1MDB scandal in Malaysia ,80 the BRI appears to be a strategy that is facilitating corruption in BRI partner countries to the political and economic benefit of the Chinese party-state and the corrupt leaders of those countries.81 This spells trouble for the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs. According to the global anti-corruption NGO Transparency International, there can be “no sustainable development without tackling corruption.”82

Commitments to fighting corruption and bribery and increasing transparency and accountability are specific targets under Sustainable Development Goal 16, “Peace, justice and strong institutions.” At a meeting commemorating the 15th anniversary of the adoption of the UN Convention against Corruption in May 2018, the then President of the General Assembly, Miroslav Kajčák, noted that battling corruption was vital not only to realizing SDG 16, but to the success of the entire 2030 Agenda.83 Other targets for SDG 16 include the promotion of rule of law and equal access to justice, and ensuring “public access to information” and the protection of “fundamental freedoms, in accordance with national legislation and international agreements.”

Xi Jinping’s New Era is not exactly a poster child for SDG 16. It is difficult to discern any positive governance or justice outcomes within China as a result of the BRI. On the contrary, Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities in Xinjiang, a “core region” for the BRI,84 are suffering egregious human rights prompted in part by the BRI, which President Xi and other Chinese officials have used to justify intensified “stability” measures in Xinjiang.85 A professor at the Shanghai Municipal Center for International Studies, Wang Dehua 王德华,86 told the Financial Times, “Xinjiang is a crucial element in the BRI because two of its economic corridors pass through [the region].… Without Xinjiang’s stability, nothing else can be achieved.”87

The Party-state is also focused on Tibet, and how Tibetan Buddhism can further its BRI goals. Jichang Lulu noted in 2017 that the Party secretary of the High-level Tibetan Academy of Buddhism (中国藏语系高级佛学院) Wang Changyu 王长渔 opined that the academy could assist Belt and Road countries “satisfy their demand for religious specialists and scriptures.”88 Last October, the Global Times reported on a two-day meeting of Tibetan monks and scholars in Qinghai province “to discuss how Buddhism could better serve China’s Belt and Road initiative and resist separatism.”89 A scholar from Tsinghua claimed that the BRI would stabilize the region, and bring economic gains through cross-border trade and cultural tourism. “Stability” in China generally, and particularly with respect to Xinjiang and Tibet, is synonymous with securitization and repression. Key tools of “stability maintenance,” including technology for tight Internet control and digital surveillance, will be exported along the BRI’s Digital Silk Road.90

China’s strong-arm tactics and repression in furtherance of BRI interests are evident in the far reaches of the BRI in Africa, and just across the border in Kazakhstan, to give just two examples.91 The recent arrest of a Kazakh human rights activist, Serikhan Bilash, reportedly on the charge of “inciting ethnic hatred” for the work he and his advocacy group, Atajurt, were engaged in on behalf of victims of Xinjiang’s “re-education camps,”92 demonstrates how BRI stability interests (and corruption)93 can lead to human rights abuses and the undermining of the SDGs.

Despite the party-state’s rhetoric that the BRI belongs to everyone, and that it’s all about “win-win cooperation,” etc., the BRI should be treated as a fundamental part of China’s “long arm” strategy—- as a vehicle for spreading influence, control and repression. While certain positive outcomes have resulted from the BRI (and Chinese investment and aid before the BRI)—- such as badly needed infrastructure getting built in some developing countries—- there is scant evidence that the BRI is contributing meaningfully to the achievement of the 2030 Agenda. Instead, the PRC and its BRI pose a substantial threat to the entire Agenda and the SDGs —- and many people (the more than one million Uyghurs detained in camps, for starters) are at risk to be “left behind.”

Andréa Worden, J.D., is a researcher, translator and consultant whose work focuses on human rights and rule of law in China, and China’s interactions with the UN human rights mechanisms. She will be a visiting lecturer this fall in the East Asian Studies Program at Johns Hopkins Krieger School of Arts & Sciences.

- Colum Lynch, “China Enlists U.N. to Promote Its Belt and Road Project”, Foreign Policy (2018).↩

- Sinopsis and Jichang Lulu, “United Nations with Chinese Characteristics: Elite Capture and Discourse Management on a global scale”, Sinopsis (2018).↩

- Permanent Mission of China at the UN, “Remarks by Ambassador Ma Zhaoxu at High-level Symposium on Belt and Road Initiative and 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” (2018).↩

- Hannah Beech, “‘We Cannot Afford This’: Malaysia Pushes Back Against China’s Vision”, The New York Times (2018).↩

- Cao Desheng 曹德胜, “BRI hailed as force for sustainable development”, China Daily (2019).↩

- Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD), Defending Rights in a “No Rights Zone”: Annual Report on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders in China (2018) (2019).↩

- Shanthi Kalathil, “How Beijing is Reshaping the Infrastructure of Development”, Power 3.0 (2018).↩

- Nadège Rolland, “Beijing’s Vision for a Reshaped International Order”, China Brief 18:3 (2018).↩

- United Nations General Assembly, A/RES/70/1: Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2015); International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), “Sustainable Development Goals”.↩

- United Nations, Consensus Reached on New Sustainable Development Agenda to be adopted by World Leaders in September (2015).↩

- Bill Orme, “Can Good Governance Become a Global Development Goal?”, Pass Blue (2014).↩

- United Nations, “Millennium Development Goals”.↩

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), “Human Rights and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”.↩

- OHCHR, “Keynote remarks by ASG Andrew Gilmour, OHCHR at the HLPF Plenary Session, Leaving no one behind: Are we succeeding?” (2018).↩

- OHCRH, “Human Rights and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”.↩

- Globalgoals.org, The 17 Goals.↩

- OHCHR, “Human Rights Council intersessional meeting for dialogue and cooperation on human rights” (2019).↩

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, “UN Human Rights Council looks to human rights and sustainable development” (2019).↩

- OHCHR, “Summary of the intersessional meeting for dialogue and cooperation on human rights and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” (2019).↩

- White House, Office of the Press Secretary, “FACT SHEET: U.S. Global Development Policy and Agenda 2030”, via National Archives (2015).↩

- Raffaela Dattler, “Not without us: civil society’s role in implementing the Sustainable Development Goals”, Entre Nous 84 (2016).↩

- African Civil Society Circle, The Roles of Civil Society in Localising the Sustainable Development Goals, ACORD (2016).↩

- Livia Bizikova and Fraser Reilly-King, “Do We Need To Engage Civil Society Organizations in Implementing SDGs?”, SDG Knowledge Hub (2017).↩

- Ivonne Lobos Alba and Jes Weigelt, “Strengthening Civil Society to Influence the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda”, SDG Knowledge Hub (2016).↩

- United Nations, “How to apply for consultative status with ECOSOC?”, “Committee on Non-Governmental Organizations Recommends Status for 70 Groups, Defers Action on 40 Others as It Opens 2019 Regular Session” (ECOSOC/6954-NGO/878) (2019).↩

- State Council Information Office (SCIO), 《发展权:中国的理念、实践与贡献》白皮书 (2016).↩

- Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action (1993) via OHCHR.↩

- Human Rights Watch (HRW), “China should end restrictions on civil society participation in anti-poverty policies, and cooperate with UN mandate-holders without interference” (2017).↩

- SCIO via Renmin wang, 《中国人权状况》白皮书(一九九一年十一月·北京) (2000); Katrin Kinzelbach, ”China’s White Paper on Human Rights”, GPPi (2016).↩

- Andréa Worden, “China Pushes ‘Human Rights With Chinese Characteristics’ at the UN”, China Change (2017).↩

- Andréa Worden, “China Deals Another Blow to the International Human Rights Framework at its UN Universal Periodic Review”, China Change (2018).↩

- Xinhua via gov.cn, 改革开放40年中国人权事业的发展进步 (2018); Xinhua, “China issues white paper on human rights progress over 40 years of reform, opening up” (2018).↩

- Xinhua, “Rights to subsistence, development of Chinese people better protected: white paper” (2018).↩

- Lin Songtian 林松添, “China is setting up a new model for world human rights”, Independent Online (2019).↩

- Renmin wang, 中国驻南非大使发表署名文章《中国为世界人权事业树立了新典范》 (2019).↩

- Wei Zhezhe 魏哲哲, 人民幸福生活是最大的人权, Renmin ribao (2018).↩

- Nick Cumming-Bruce, “U.N. Panel Confronts China Over Reports That It Holds a Million Uighurs in Camps”, The New York Times (2018).↩

- Global Times, “Protecting peace, stability is top of human rights agenda for Xinjiang” (2018).↩

- Permanent Mission of China at the UN, “Statement by Ambassador Wu Haitao at the General Debate on Human Rights of the Third Committee of the 73rd Session of the General Assembly” (2018).↩

- Andréa Worden, “With Its Latest Human Rights Council Resolution, China Continues Its Assault on the UN Human Rights Framework”, China Change (2018).↩

- Nathan Vanderklippe, “China takes aim at civil society in systematic crackdown: report”, The Globe and Mail (2017).↩

- CIVICUS, “China”↩

- CHRD, op. cit.↩

- HRW, [The Costs of International Advocacy. China’s Interference in United Nations Human Rights Mechanisms])https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/09/05/costs-international-advocacy/chinas-interference-united-nations-human-rights) (2017).↩

- CHRD, “Hold Chinese Government Accountable for Reprisals Against Human Rights Defenders Cooperating with UN – Aggressive Moves Target Activists and NGOs in China & Abroad” (2018).↩

- United Nations General Assembly, Cooperation with the United Nations, itsrepresentatives and mechanisms in the field of human rights (A/HRC/39/41) (2018).↩

- United Nations Secretary-General, “Secretary-General’s remarks to General Assembly on Human Rights Defenders [as delivered]” (2018).↩

- Andréa Worden, “As the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders Turns 20, China Wages a Multi-Pronged Attack on Rights Defenders”, China Change (2018).↩

- China Law Translate, [“Criminal Law (2017 Revision)”](https://www.chinalawtranslate.com/en/刑法-(2017年修正版)/] (2017); Xingshi bianhu wang, 中华人民共和国刑法 (2018); CHRD, Defending Rights in a “No Rights Zone”.↩

- Lynch, op. cit.; Sinopsis and Lulu, op. cit.; Alvin Lum and Emma Kazaryan, “Former Hong Kong minister Patrick Ho Chi-ping convicted in US court on 7 of 8 counts in bribery and money-laundering case” (2018).↩

- Permanent Mission of China at the UN, “Remarks by Ambassador Ma Zhaoxu”.↩

- For background on the study, see Sinopsis and Lulu, op. cit.↩

- DESA, “Statement — Belt and Road Legal Cooperation Forum” (2018); see DESA, “Mr. Liu Zhenmin, Under-Secretary-General”.↩

- Belt and Road Portal, “People-to-people Bond”.↩

- CGTN via China Daily, “Belt and Road Initiative yields fruitful results in the cultural arena” (2018).↩

- Xinhua via China Daily, “Confucius Institutes lauded in promoting ‘Belt and Road’ initiative” (2016).↩

- Xinhua via Belt and Road Portal, “Charity program to donate stationery to B&R countries’ pupils” (2019).↩

- UN News, “At China’s Belt and Road Forum, UN chief Guterres stresses shared development goals” (2017).↩

- Lynch, op. cit.↩

- Erik Solheim, “Establishing green routes for growth”, China Daily (2017).↩

- Damian Carrington, “UN environment chief resigns after frequent flying revelations”, The Guardian (2018).↩

- Oli Brown, “Erik Solheim: what he got right, what he got wrong, and what the new UN Environment chief should do next” (2019).↩

- DESA NGO Branch, “China Energy Fund Committee” (consultative status search result).↩

- US Department of Justice, “Patrick Ho, Former Head Of Organization Backed By Chinese Energy Conglomerate, Convicted Of International Bribery, Money Laundering Offenses” (2018).↩

- Andréa Worden, Twitter post (2019).↩

- SCRIC, Home page, “About SRCIC”.↩

- On CCPIT and United Front work, see Martin Hála and Jichang Lulu, “The CCP’s model of social control goes global”, Sinopsis; Lulu, Twitter post (2018).↩

- Belt and Road Portal, Chinese, English.↩

- Andréa Worden, Twitter post (2019).↩

- The China Chamber of International Commerce (中国国际商会). See, e.g., MOFCOM, 中国国际贸易促进委员会的成立; CCPIT, 中国国际贸易促进委员会章程 (2015).↩

- Renmin wang, 全国政协第十届委员会委员名单 (2008), 中国人民政治协商会议第十一届全国委员会委员名单 (2008), 中国人民政治协商会议第十二届全国委员会委员名单 (2013); Xinhua via Renmin wang (2018), 中华人民共和国第十三届全国人民代表大会代表名单; SRCIC, 商会领导; CCPIT, 中国国际商会副会长吕建中拜会国际商会总部 (2014);↩

- Xinhua, 发挥民间工商力量推进“一带一路”建设–访丝绸之路国际总商会主席吕建中 (2017).↩

- Minxin Pei, “Will China let Belt and Road die quietly?”, Nikkei Asian Review (2019); Keith Bradsher, “China Proceeds With Belt and Road Push, but Does It More Quietly” (2019); but cf. Nadège Rolland, “Reports of the Belt and Road’s death are greatly exaggerated” Foreign Affairs (2019).↩

- Beltandroad2019.com↩

- Daily Nation via The East African, “SGR pact with China a risk to Kenyan sovereignty, assets” (2019).↩

- International Crisis Group, Fire and Ice: Conflict and Drugs in Myanmar’s Shan State (2019).↩

- Isabel Hilton, “How China’s Big Overseas Initiative Threatens Global Climate Progress”, Yale E360 (2019).↩

- Christopher Balding, “Why Democracies Are Turning Against Belt and Road”, Foreign Affairs (2018).↩

- Chang Ping, “One Belt, One Road, Total Corruption”, China Change (2017).↩

- Beech, “‘We Cannot Afford This’”.↩

- Will Doig, “The Belt and Road Initiative Is a Corruption Bonanza”, Foreign Policy (2019).↩

- Transparency International, “No sustainable development without tackling corruption: the importance of tracking SDG 16” (2017).↩

- United Nations General Assembly, “Battle against Corruption Vital to 2030 Agenda, General Assembly President Tells High-level Commemoration of Anti-Corruption Treaty’s Adoption” (GA/12017) (2018).↩

- Ben Mauk, “Can China Turn the Middle of Nowhere Into the Center of the World Economy?”, The New York Times (2019).↩

- Michael Clarke, “In Xinjiang, China’s ‘Neo-Totalitarian’ Turn Is Already a Reality”, The Diplomat (2018).↩

- Professor Wang Dehua 王德华 (b. 1938) holds an assortment of titles and positions, including Director of the Institute for South and Central Asian Studies at the Shanghai Municipal Center for International Studies (上海国际问题研究中心). Interestingly, he has received funding from CEFC and conducted research under the auspices of the CEFC-Jiaotong University International Energy Research Center (IERC, 国际能源问题建就中心). See IERC, 国际能源问题建就中心——研究团队, 简介, 领导贺词; Zhang Tingting 张庭婷 [an IERC researcher] and Wang Dehua 王德华, “一带一路”背景下中国与海合会能源合作关系与展望, 印度洋经济体研究 2017:3, via CNKI.↩

- Emily Feng, “Crackdown in Xinjiang: Where have all the people gone?”, Financial Times (2018).↩

- Jichang Lulu, “State-managed Buddhism and Chinese-Mongolian relations”, The Asia Dialogue (2017).↩

- Zhang Han, “Buddhism encouraged to serve BRI”, Global Times (2018).↩

- Stewart M. Patrick, “Belt and Router: China Aims for Tighter Internet Controls with Digital Silk Road”, cfr.org (2018).↩

- Sheridan Prasso, “China’s Digital Silk Road Is Looking More Like an Iron Curtain”, Bloomberg (2019).↩

- Radio Free Asia, “Activist Under House Arrest in Kazakhstan, Prompting Fears of Pressure From China” (2019).↩

- Doig, op. cit.↩