The term “Indo-Pacific,” which came into use around 2010, has been booming worldwide in recent years, including in Europe. It is a buzzword, and each actor who uses it has a different meaning and expectations in mind. However, it is not widely known that Japan was the first country to use this term in its “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” (FOIP) concept.

The FOIP, an original concept announced by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in Kenya in August 2016, started as a key element of Japan’s diplomatic vision to contribute to the development of the Indo-Pacific region and strengthen Japan’s presence in the region, especially in ASEAN countries, where its influence has waned due to a domestic economic recession and expanding Chinese power. However, the change in the regional balance of power, which reflects China’s growing hard power in terms of both economic and military strength, and the Trump administration’s hard-line stance toward China, have increased the importance of restraining China’s assertive behavior in the Indo-Pacific. So, starting in 2017, the concept was referred to as the “FOIP Strategy (a word “strategy” was later removed because of its overly military connotations).” More recently, thanks to a growing number of participants in the Indo-Pacific, including ASEAN and European countries, coupled with the EU realizing the geo-economic and geopolitical importance of the “Indo-Pacific,” Japan’s FOIP has been transformed into a “fundamental vision for broader multilateral cooperation” for countries that share the common rules.

Therefore, it is possible to say that the FOIP has a threefold purpose: first, contributing to regional development in the Indo-Pacific region while emphasizing Japan’s contribution; second, restraining China’s assertive behavior and challenges; and third, offering a broader vision for multilateral cooperation to protect the liberal international order. However, as the contours and balance of Japan’s relations with the U.S. and China have changed, it has become difficult to discern which of these three elements is a priority for Japan, and to get a complete picture of Japan’s FOIP.

1. Contributing to regional development in the Indo-Pacific region with nonmilitary aid

After World War II, which resulted in the deaths of 3.2 million Japanese, both military and civilian, and inflicted great damage on Asian countries, especially the current ASEAN members, Japan adopted a postwar Constitution that rejects “solving international disputes by force,” allows only the right of self-defense, and limits possession of strategic offensive capabilities. It is often pointed out that Japan has developed an anti-military culture that rejects any kind of war and the “use of force” (Katzenstein 1996; Berger 1998). Some critics insist that this is a “sham pacifism” created by the existence of the “extended nuclear deterrence” and conventional deterrence provided by the U.S. (Lind 2004; Miyashita 2006). But it is undeniable that most Japanese people are still cautious about the use of force because they fear being drawn into war.

As a result, Japan’s international contributions have not been in the form of direct military force, but rather in nonmilitary contributions such as infrastructure, social welfare projects centered on economic assistance, and education and training. However, with the recent rapid expansion of China’s economic power and growing influence, and Japan’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) hampered by a limited budget, there has been widespread concern, especially among diplomats, that Japan’s presence in the region is being drowned out.

Japanese public broadcaster NHK interviewed (Japanese only) Ichikawa Keiichi, then-Director of the General Affairs Division, Foreign Policy Bureau, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who created Japan’s FOIP concept. He cited a sense of crisis over Japan’s declining presence in the international community as the background for the birth of the FOIP concept. Taking a cue from Prime Minister Abe’s “Intersection of Two Oceans” speech in India in August 2007, Ichikawa recognized the importance of focusing Japan’s diplomatic resources on the Indo-Pacific region, which connects the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, and the need to create a coherent message to promote it. After exchanging views with officials from various ministries and agencies, he finally came up with a message that the region should be “free and open to all.” Takeo Akiba, then-Director General of the Foreign Policy Bureau, agreed with this. As a result, then-Prime Minister Abe announced the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” concept at the sixth Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD-6) in Nairobi, Kenya in August 2016.

The Abe administration explained the vision as consisting of three pillars: (1) upholding the rule of law, freedom of navigation, and other principles; (2) pursuing economic prosperity; (3) ensuring peace and stability through enhancing “connectivity” between Asia and Africa, and between the Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean, through infrastructure construction, “capacity building” and educational projects. This concept also aims to apply the knowledge of ASEAN countries that have been successful in economic and social development to African countries and the Indian Ocean Rim countries to help achieve stability and prosperity for the region. For Japan, which depends on Sea Lines of Communication (SLOC) for imported resources and other international trade, as well as maritime security, energy security and economic security, including supply chain stability, this is an extremely important concept.

In particular, as the nexus between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, the ASEAN region is of vital importance to Japan’s maritime security. So relations have been prioritized to strengthen this region. The symbol of Japan’s contribution to ASEAN countries is the “Vientiane Vision,” which was announced at the ASEAN-Japan Defense Ministers’ Meeting held at the initiative of then-Prime Minister Abe in Vientiane, the capital of Laos, in November 2016. This is the first statement by the Japanese Ministry of Defense expressing Japan’s active engagement through “defense diplomacy (military diplomacy),” which offers non-combat military assistance to support “capability building” for maintaining regional order based on the rule of law while ensuring the unity of ASEAN.

This vision aims to promote ASEAN countries’ understanding of international law in the maritime and aviation fields, and to improve their intelligence-gathering, surveillance, and search-and-rescue capabilities through a combination of specific capacity-building support, defense equipment transfers, and technical assistance, along with training and human resource development. The goal is to strengthen the principle of the “rule of law” while maintaining the principles of ASEAN centrality and ASEAN unity. Furthermore, Japan’s efforts to support capacity building in ASEAN countries also lent support to the Obama administration’s “rebalancing” strategy to refocus on Asia. The defense diplomacy was upgraded in November 2019 to “Vientiane Vision 2.0,” which emphasizes a linkage between the East China Sea and the South China Seas, and shifts from a bilateral project base to a multilateral one.

ASEAN countries such as Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines had limited surveillance capabilities to monitor piracy, crime organizations, terrorists and illegal fishing activities in their territorial waters and Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ). To build up those countries’ capabilities, Japan provided 35 patrol vessels, 13 small speedboats and 11 coastal surveillance radar units through a combination of ODA from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, defense diplomacy by the Ministry of Defense, and additional support from the Japan Coast Guard. In addition, experts have been dispatched from Japan, seminars on the law of the sea have been held, and experts from ASEAN countries have been invited to Japan for training. It is particularly important to note that Japan is focusing on capacity-building to support maritime law enforcement agencies such as the Coast Guard, which run what are known as “white hull (coast guard cutters)” rather than “gray hull (naval vessels),” focused on preventing crises and avoiding escalation.

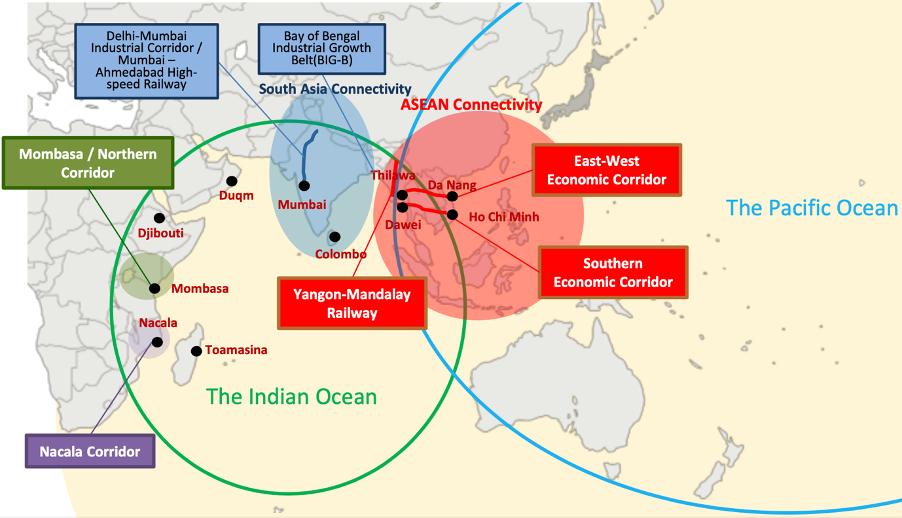

In addition to defense diplomacy, infrastructure improvements are underway to enhance connectivity, including the rehabilitation of the East-West Economic Corridor, the Southern Economic Corridor, and the Yangon-Mandalay Railway. Japanese companies are also involved in a wide range of projects in the areas of electric power, ports, railroads, urban development, industrial parks, manufacturing (value chain and human resource development), and food and agriculture. As seen here, the FOIP projects are a patchwork of projects from each of the various actors.

(Source: Free and Open Indo-Pacific, Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

2. Restraining China’s assertive behavior and challenges

In recent years, propelled by long-term plans and a strong political will for the “great rejuvenation of China” with Han Chinese supremacy over the West, the Chinese armed forces, which consist of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the People’s Armed Police (PAP), and various militias, has continued to expand both qualitatively and quantitatively. Beijing’s efforts to “change the status quo by force” have become a serious concern in the Indo-Pacific region.

When Xi Jinping announced military reform in November 2015 while reducing the actual number of forces by 300,000, he also established a “Strategic Support Force” (SSF) to collect and disseminate information from cyber operations and space platforms as an independent military branch, along with the army, navy, air force and strategic rocket force, to improve the PLA’s capabilities in the information warfare era. In addition, at the 19th Central Committee meeting, “Multidomain Intelligentized Warfare,” which combines military operations in the cyber, outer space and electromagnetic domains in addition to the traditional domains of land, sea and air, was explored. Furthermore, so-called “military-civilian fusion” (MCF), which combines military and civilian technologies and applications in such diverse fields as drones, AI and disruptive technologies, is also underway, and its challenges are not limited to the traditional military domain.

In particular, it is important to note that Chinese authorities have recognized the strategic necessity of maritime security as a core national interest and strengthened the country’s naval capabilities. In late July 2013, Xi Jinping emphasized the importance of maritime supremacy, including strengthening naval power, enhancing maritime law enforcement capabilities, building a maritime militia, and establishing maritime laws and regulations. It is a continuation of the policy of then-General Secretary Hu Jintao, who declared China would “resolutely protect the nation’s maritime interests and build a strong maritime power” at the 18th National Congress in November 2012.

As a result, according to the U.S. “2021 Annual Report to Congress” published in November 2021, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) became the largest navy in the world with 355 naval vessels. Of course, the U.S. Navy’s number of aircraft carriers, assault landing ships and attack submarines, as well as qualitative aspects such as carrier-capable aircraft, radar censors and experience are still superior to China’s. But considering the limits on naval forces that can be deployed in the Western Pacific by the U.S. Navy, which has to maintain a global forward deployment posture at all times, Chinese naval capabilities in the Western Pacific exceed those of the U.S. Navy in the area, which has become the new norm as the deterrence provided by U.S. conventional forces is gradually declining.

For example, China’s defense spending in 2021 (official figures) will increase by 6.8% to 135.5 billion yuan ($178.16 billion), 42 times more than 30 years ago, and the 2022 budget will increase to 145 billion yuan ($230.16 billion), an increase of 7.1% over the previous year. And it should be noted that China’s actual military-related spending is higher than the announced budget. Another clear example of Chinese dominance: PLAN commissioned 19 major naval vessels in 2021, compared to seven for the U.S. Navy and only three for the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force.

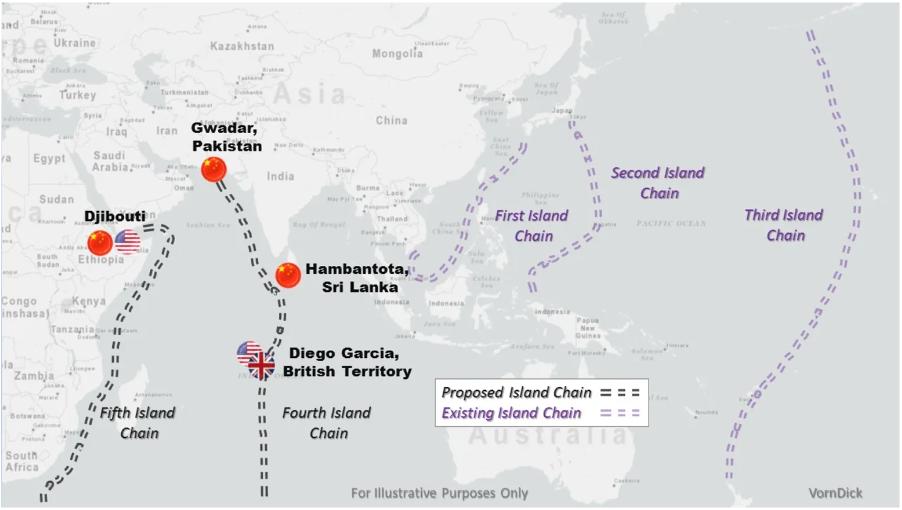

In addition, the areas where China is attempting to expand its military and economic presence and diplomatic influence are also expanding from within the so-called “First Island chain,” which includes the South China Sea and East China Sea, toward the “Second Island chain” connecting the Ogasawara Islands, Guam and Palau, and even toward the “Third Island chain” connecting the Aleutian Islands, Hawaii and Tonga. Along with Tonga, China recently strengthened relations with the Solomon Islands, which signed a security agreement with China in April 2022 that gives Chinese naval vessels port call privileges and island authorities the right to request Chinese troops and police deployment, and Kiribati, which terminated diplomatic relations with Taiwan in 2019 and is trying to strengthen relations with China. All this has heightened a sense of crisis among Australia, the U.S. and others.

(Source: China’s reach has grown: So should the Island chains. CSIS, 2018)

It is important to note that Xi Jinping understands global structure within the theory of historical materialism, “the reality of substructure (global economy) development should be reflected in the superstructure (global politics),” and that China’s position in international politics and international law should be adjusted according to its success in substructure. Furthermore, Xi Jinping’s high regard for Mao Zedong’s philosophy, which emphasized the importance of “independence and self-reliance” and “self-reliance rehabilitation,” has led him to emphasize Chinese self-respect and confidence without imitating foreign models, and to promote China’s military and maritime power through Han Chinese-centric rhetoric about the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation as “Chinese Dream.”

As a result, in November 2017 the Trump administration outlined its vision for “free and open Indo-Pacific,” renamed the U.S. Pacific Command and then the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command in May 2018. In October that year, U.S. Vice President Mike Pence added to the pressure on China with a strong speech of concern. In Japan, the term “Indo-Pacific” was increasingly mentioned in the context of checks and balances against China, and FOIP was described as an official “strategy” for the first time within the 2017 Diplomatic Blue Book. However, the word “strategy” was removed from Japan’s FOIP strategy when Prime Minister Abe changed his policy towards improving relations with China. This was done at the behest of advisors from the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry advocating for the Japanese business community, which wants to maintain stable relations with China.

In this way, the contradictory approaches of fostering inclusive regional development to help ensure a balance against an increasingly powerful China, while continuing Japan’s “separation of politics and economics” policies, which segregate political and economic relations with China, aiming first and foremost at stabilizing economic relations, are the main culprits that make Japan’s FOIP and its shifting contributions difficult to understand.

3. Offering a broader vision for multilateral cooperation

The “ASEAN Outlook of the Indo Pacific (AOIP)” was adopted at the June 2019 ASEAN Summit, with ASEAN members pointing out the strategic importance of ASEAN in the Indo-Pacific as the linchpin connecting the Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean, and insisting that nobody in the region should be excluded or put at an economic disadvantage. In other words, FOIP’s basic principle of “free and open” should be universal. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi also rejected the exclusivity of the Indo-Pacific at the 2019 Shangri-La Dialogue, arguing that it is not a club of a limited number and is not meant to discriminate against anyone.

European countries also pointed to the importance of inclusiveness and the multilateral principle in their own Indo-Pacific policy documents: France in 2018, Germany and the Netherlands in 2020, and the EU in 2021. These documents indicate their understanding that the geo-economic and geopolitical center of gravity have shifted to the East, and suggest a wide range of strategic goals that encompass sustainable development, maritime security and maintaining a free trade regime. As a result, the FOIP, which had been on the verge of becoming more nuanced in its attempts to put pressure on China, was adjusted to a vision of “broader multilateral coordination.” This reflects Japan’s intention to make the FOIP a loose common vision for as many actors as possible, giving them a chance to participate and adjust the content to their own vision.

During the IISS Shangri-La Dialogue in June 2022, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida announced the “Kishida Vision for Peace” to maintain and strengthen a rule-based, free and open international order in which all countries are treated equally – no country stands out, and the national interests of all participants are respected. He also declared that Japan would announce an “FOIP Plan for Peace” allocating Japan’s Official Development Aid (ODA) to contribute to regional development through infrastructure, capacity building, education and strengthening international cooperation for economic security by the spring of 2023.

In this context, FOIP is not a single, robust framework, but rather a base vision for combining various frameworks and initiatives in a multilayered and multidimensional manner. It provides a free space for all actors to bring their own political will, funds and other assets, and to seek voluntary contributions for national and regional interests based on certain common rules, such as the “rule of law” and “freedom of navigation and overflight.” In this loose framework, Japan’s role has deliberately been made invisible in order to promote voluntary contributions from each country. In this context, the ideal, aspirational goal of Japan’s FOIP is to create a region where all nations are respected and treated equally, without any one nation standing out, irrespective of their size and economic clout.

In fact, there are already many frameworks for cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. For example, AUKUS, which aims to improve defense capabilities by helping Australia acquire nuclear submarines with the help of the U.S. and U.K.; QUAD, a cooperative framework for economic security that includes Japan, the U.S., Australia and India; ASEAN, which is an important regional framework between the Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean; the U.S.-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), which aims to enhance U.S. presence in the region through economic security; the Blue Dot Network, which aims to improve transparency by reviewing and certifying infrastructure investment by the U.S., Japan and Australia; the CPTPP, which was originally intended to be a free trade area in which the U.S. would be included; the RCEP, a comprehensive economic partnership agreement that includes ASEAN countries, Japan and China; and various other bilateral and trilateral cooperation agreements.

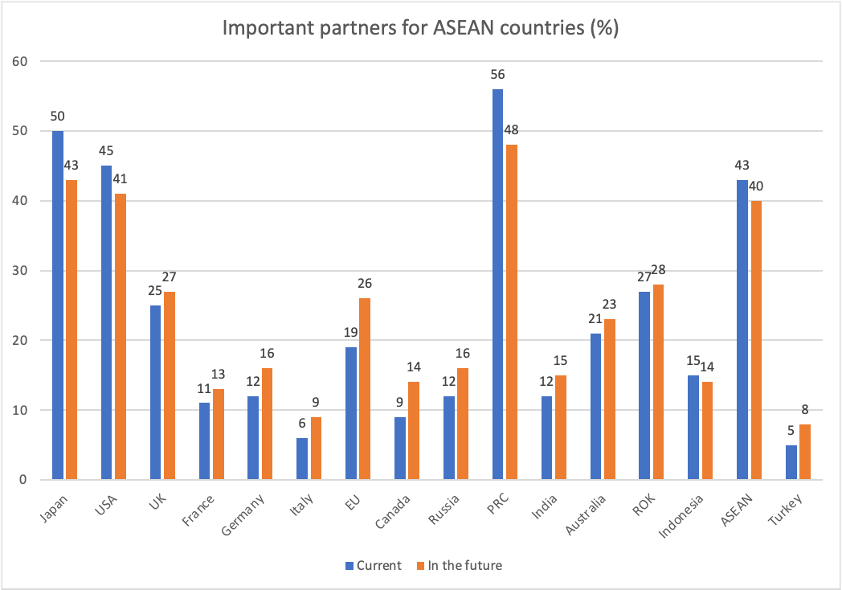

At the same time, avoiding direct military conflict with China remains a priority. Former Prime Minister Abe kept relatively pragmatic economic relations with China, and now the question is how that posture will be changed by the Kishida administration in the face of growing China-focused pressure from the U.S. especially following Abe’s assassination. This helps explain why expectations among ASEAN countries for involvement by European countries have never been higher (see graph below). ASEAN countries are not only looking forward to European countries’ contributions and support in nonmilitary fields, but also seeking to neutralize the influence of hostile entities among external powers by forging alliances with friendly external powers.

(Source: ASEAN Opinion survey (in Japanese only), Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, January 2022)

In the wake of Russia’s brutal and illegal invasion of Ukraine, we recognize there are states that still believe in “changing the status quo by force,” and criticize the existing international order as outdated. They form strategic partnerships and attempt to erode the prosperity and liberal international order based on the “rule of law” principle. The Czech Republic is not immune to these challenges. Daily lives and supply chains for Czech industry depend heavily on SLOC in the Indo-Pacific, through which two-thirds of global logistics passes. In addition, attempts to undermine democracies and destroy cohesion among the liberal democratic countries through cyber warfare, disinformation campaigns, and data and technology theft include attacks that have already occurred in the Czech Republic, even though it is far from the region.

Thus, it is important to encourage Indo-Pacific countries, some of whom cannot explicitly criticize Russia due to strategic calculations and other reasons, to join the international movement rejecting the grand misconceptions that “might makes right” and “money makes right,” and “nuclear powers have privileged status.” In other words, it is crucial to support regional countries in the Indo-Pacific to develop their own capabilities, and encourage European countries to engage in the Indo-Pacific in defending the liberal international order by binding their political will, multi-domain assets and funds, and making a like-minded alignment in the FOIP framework to coordinate their cooperation. Therefore, we need to pay attention to the Kishida administration’s foreign policy to see which of the three elements of the FOIP Japan wants to focus on and what kind of international role Tokyo intends to play in the FOIP.