An unusually blunt warning by Czech intelligence against the use of Huawei and ZTE products in telecommunications infrastructure was met with similar bluntness from the PRC. The embattled Babiš government, whose survival depends on the support of the country’s most CCP-friendly figures, was subjected to a pre-Christmas diplomatic ritual hyped by the state-media as “correcting” the spooks’ “mistaken” advice. After an outrage in the Czech Republic, the PM backpedalled and reiterated the NÚKIB warning was being treated “seriously”.

The Party-state’s concerted diplomatic and propaganda effort spent on awaking Czech politics from Yuletide hibernation and attempting to neutralise the intelligence warning signals the strategic stakes: a Czech Huawei ban could trigger a domino effect in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), a region still untouched by the wave of Western measures against the use of its equipment in 5G networks. Should Poland, in particular, join the Czech and Anglophone scepticism, Huawei could risk losing the region’s biggest market, and the one where it has placed its biggest 5G bet.

This post summarises some of the open-source evidence on Huawei’s background and practices behind the concerns about the company aired in the Czech Republic and elsewhere, before illustrating the PRC’s likely fears of CEE contagion with a brief discussion of the Polish case. The peculiar pre-Christmas démarche involving Babiš, the PRC embassy and the domestic and external propaganda machine is described in the context of the support Huawei frequently enjoys from state media and foreign entities cultivated through ‘friendly contact’ activity, a connection demonstrated in Australia and New Zealand.

The PR strategies Huawei has adopted, as well as its targets, overlap with those encountered in the analysis of global United Front work; the Party-state’s support for the company demands a wider discussion informed by the CCP’s international influence operations, a main focus of Sinopsis’ coverage of the Czech Republic and other locales. The Polish case neatly illustrates this connection: a local Huawei interlocutor is known as a contact favoured by the CCP’s International Liaison Department, a Comintern-inspired organ whose expansion to general political influence work we have been describing in a series of posts.

Among Huawei’s links to the Party, state and Army, its collaboration with Public Security in the PRC and, in particular, Xinjiang, could make its role in state surveillance and repression of particular interests in Central and Eastern Europe, a region that had found itself on the receiving end of the earlier totalitarian regimes. Huawei’s technology is among those that could fuel an upgrade of the CCP’s systems of social control to a new level of authoritarian governance; as Lenin stressed, Communist rule relies on both Party power and technological breakthroughs. For Lenin, Communism was Soviet power plus electrification; extrapolating, Xi’s New Era is orthodox Communism plus “intelligentisation” (智能化).

Huawei as a Party-state champion

Open-source information and previous statements from the intelligence community squarely back up the concerns aired by Czech cyber-intelligence.

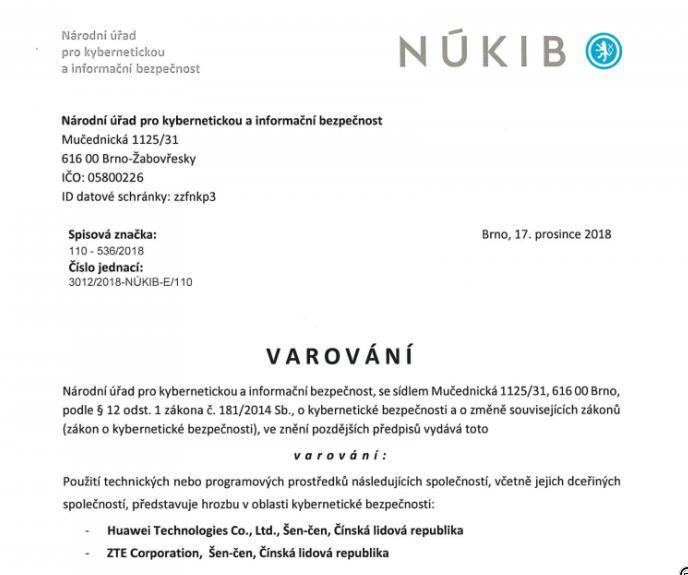

The warning, issued by the National Cyber and Information Security Agency (Národní úřad pro kybernetickou a informační bezpečnost, NÚKIB) on 17 December, calls the use of software and hardware products of Huawei, ZTE and their subsidiaries a “threat against information security”. According to Czech press reports, the warning was originally meant as a classified document for internal government discussion. The unusual step of going public reportedly resulted from the fact that some of the intended recipients lacked the security clearance to read the report.

Besides the companies’ legal obligation to cooperate with PRC intelligence activities, the text mentions “organisational and personnel links between these companies and the state”, the agency’s knowledge about the companies’ work in the Czech Republic and the PRC’s “influence and espionage” activities there to justify fears that the presence of Huawei or ZTE products in information or communication systems could affect “the security of the Czech Republic and its interests”.

The 2017 National Intelligence Law (国家情报法) mandates “all organisations and citizens” to collaborate with intelligence work as requested. This legal obligation and the characteristics of the activity of such companies as Huawei and ZTE makes such ‘requests’ likely. As Elsa Kania notes,

[T]he trend towards fuller fusion between the party-state apparatus and commercial enterprises—and the ways in which that fusion might be leveraged to support intelligence work—should be taken into account in business and governmental assessments of risk.

Huawei’s current and previous top management includes individuals with backgrounds in the PLA, military-linked universities and the Ministry of State Security.

Huawei chairman Ren Zhengfei 任正非 was enlisted in the PLA between 1974 and 1983, after which he went on to manage Huawei using “Mao Zedong’s military thought”.

Sun Yafang 孙亚芳, Ren’s “most trusted deputy” and Huawei’s chairwoman until 2018, studied at the Radio Technology Department of the Chengdu Institute of Radio Engineering (成都电讯工程学院), then still under the joint management of the PLA General Staff Department. (The Institute’s successor, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China (UESTC, 电子科技大学), remains committed to servicing national defence and takes pride in its military research, one foot of its research “tripod”. Hacker groups linked to UESTC were allegedly behind attacks (p. 37f.) against Indian targets, including the Offices of the Dalai Lama.) After graduating, Sun did communications work at the Ministry of State Security, the PRC’s main spy agency, until joining Huawei in 1992. According to Chinese press reports, these connections helped the company obtain state support when experiencing financial difficulties.

The company’s early contracts with the PLA, while a small part of its sales, were reportedly seen as important in terms of “relationships”. Kania estimates that Huawei is “still engaged in defence-related research and development”, citing its recent participation in projects related to civil-military fusion. Adam Ni, an expert on the PLA, argues that Huawei, although a private company, depended for its success on the state’s support “through a combination of protectionist measures, cheap financing, subsidies, favourable regulations, and diplomatic support abroad”.

A recent investigation by Danielle Cave found that Huawei was “the key ICT provider” for the African Union’s headquarters, whose servers had been transferring data to China until the breach was discovered, implying that the company was either incapable of detecting, or complicit with, massive data theft.

In 2012, a US House of Representatives committee heard statements from former Huawei employees alleging illegal practices. A former employee is suing Huawei in the US, alleging the company ordered him to participate in the theft of trade secrets and retaliated against his whistleblowing. An Israeli solar-energy technology manufacturer is suing Huawei for patent infringement in Germany.

Leninism plus smart surveillance

Telecommunications infrastructure and equipment are central to surveillance, a key tool of authoritarian social control. Xi’s stress on Party control, repression and propaganda stands to benefit from emerging technologies that can take the state’s ability to monitor, analyse and shape the private behaviour of large numbers of individuals beyond the wildest dreams of his predecessors in the Leninist tradition. Propaganda, far from being drowned out by the arrival of digital and social media, has embraced it, if anything getting closer to a literal form of Lenin’s boast of having the Party’s “truth” penetrate “everyone’s head”.

Likewise, the Party-state-Army’s repressive apparatus stands to benefit from advances in surveillance technology, notably aided by artificial intelligence. Like earlier totalitarian regimes, Xi’s CCP could find a technological breakthrough empowering a ruling “vanguard” to upgrade its domination of its state and society and project social control beyond its borders, achieving what Heilmann calls “Digital Leninism”. If, as Lenin put it in 1920, “Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country”, Xiism could be Leninism plus artificial intelligence.

The security and human-rights implications of Huawei’s “smart” and “safe city” solutions are of particular relevance to the Czech Republic. Adriana Krnáčová, mayor of Prague until last month for the ruling ANO party, displayed a special interest in PRC smart-city technology: during her 2016 visit to Shanghai, she talked about smart cities “intensively” with the local government. Krnáčová revisited the topic during a meeting with the PRC ambassador the following year. The Prague government signed an agreement with Huawei on intelligent freight transport at a 2017 event that also promoted the company’s smart-city technology. Smart and “safe” cities are among the areas the company wants to cooperate” on in the next five years.

Huawei has recently partnered with the Xinjiang Public Security Bureau, aiming to guarantee the region’s “social stability”. The company signed a strategic cooperation agreement with the Xinjiang government in 2016. Huawei has partnerships with city-level public security organs throughout the country, including in Ürümqi, as well as with the national Ministry of Public Security. The involvement of companies such as Huawei and Hikvision in Tibet and Xinjiang, the CCP’s “digital Leninism lab”, further clarifies their function as tools of state policy and makes a state-subordinate role abroad even more likely.

Huawei’s exports of smart-city technology have been expanding from authoritarian and hybrid towards democratic countries. The former Soviet Union is a potentially important market, with, e.g., a smart-city project slowly progressing in Baku, a 2017 agreement in Armenia, an (aborted) deal in Kyrgyzstan and talks with local governments in Russia.

Smart-city forays farther West have arguably used the localisation tactics often deployed by PRC entities in Europe, seeking subnational-level faits accomplis by courting local officials and eschewing the attention of potentially critical national audiences.

Huawei’s ‘smart city’ project in Valenciennes seemed well received locally, with the mayor calling it “a €2bn gift to the city”.

Smart-city deals in Prague would give Huawei an upgrade from the regional successes it has seen in France and Germany to claim a capital city as it has done in Azerbaijan. It remains to be seen if the less authoritarian-friendly Czech public opinion will welcome this westward advance.

Global warnings

These circumstances have been largely known for years, and have long generated concerns among analysts, politicians and intelligence agencies in multiple countries. Only in the last few months, however, have these concerns crystallized into actual measures limiting the use of Huawei equipment, triggered by the United States and its intelligence partners rushing to exclude Huawei from 5G, the next generation of mobile phone technology.

The NÚKIB statement explicitly refers to previous warnings from Czech civilian and military intelligence. Indeed, the Czech concerns are not new: the 2013 annual report of the main Czech counterintelligence agency, the Security Information Service (BIS), called Huawei’s growing share of the local telecommunications market a “potential danger”. The use of Huawei phones at the presidential palace has generated controversy.

Since a US House of Representatives committee found in 2012 that Huawei had failed to establish its independence from the PRC state and the PLA, bad press has constantly rained on Ren’s company. That year, experts found Huawei equipment “riddled with holes”. A deal with AT&T to sell Huawei products fell through earlier this year “because of security concerns” after lawmakers from both houses wrote to the Federal Communications Commission warned about “espionage” risks. In February 2018, at a US Senate hearing, intelligence chiefs would not advise private citizens to use Huawei products.

Australia banned Huawei from the country’s broadband network in 2012. A 2016 deal to build an undersea communications cable between Australia, the Solomon islands and Papua-New Guinea was dropped over Australia’s concerns.

These difficulties pushed the company to focus on other markets, such as Europe. While Huawei has become a major player in network technology in several European countries, concerns about the security implications have been growing among analysts and security services.

Propaganda materials supportive of Huawei have used the British example to dismiss security concerns elsewhere. However, such concerns have long been present in the UK as well. In 2013, a parliamentary committee found the “self-policing arrangement” put in place to evaluate the security of Huawei equipment used in network architecture “highly unlikely” to provide “the required levels of security assurance”. Last July GCHQ downgraded their assessment of Huawei’s security, after finding shortcomings and exposing “new risks in the UK telecommunication networks”. Earlier this month, the head of the MI6 called for a “conversation” on the role of Chinese companies in the country’s 5G network, as news emerged that BT was removing Huawei equipment from its core 3G and 4G networks.

In Germany, Deutsche Telekom made headlines with a statement about “reassessing” its procurement strategy. Although the Federal Office for Information Security (Bundesamt für Sicherheit in der Informationstechnik, BSI) has explicitly denied there are grounds for a Huawei ban, some within the ruling coalition are reportedly concerned about allowing Huawei to participate in the country’s 5G network. Analysts and politicians have expressed worries over Huawei infrastructure, earlier this year in the light of the intelligence service’s public concern about cooperation between Chinese companies and PRC security services, and now specifically on the 5G issue.

The NÚKIB warning came shortly after unusually blunt statements cautioning against Huawei from the Anglophone intelligence alliance known as the Five Eyes. Intelligence chiefs from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and the US met in Canada last summer to discuss the risks presented to their countries by Huawei in particular, and the PRC more broadly. The meeting took the unusual step of making its concerns public. Four Five-Eyes prime ministers had earlier agreed in London to avoid becoming dependent on Huawei’s 5G technology.

A series of measures against public procurement in the Five Eyes countries followed. Australia banned Huawei and ZTE from its 5G network in August. In late November, New Zealand’s Government Communications Security Bureau blocked Huawei from providing 5G equipment to a telecom after identifying “a significant network security risk”. The New Zealand case is especially remarkable: with the exception of the Green Party, which had already called for an investigation of Huawei in 2012, the political class had avoided criticism or explicitly supported the company’s growth in the country.

The Danish case provides a good illustration of the effect the Five Eyes’ newly militant attitude can have on European allies, giving Huawei cause to worry about a domino effect. The Danish Defence Intelligence Service (Forsvarets Efterretningstjeneste, FE) advised in strong terms against giving Huawei access to the country’s infrastructure in a 2011 classified report, before changing its mind two years later to approve a deal with TDC, the country’s largest telecom. While politicians and media reports continued to raise suspicions about Huawei, the FE continued to defend Huawei’s presence, stating in 2015 that TDC-Huawei agreements had “increased the security” of telecommunications networks. As late as last February, reacting to US warnings against Huawei equipment, the FE saw “no concrete grounds to advise against smartphones from specific manufacturers of countries”. Following the MI6 head’s recent statements, however, his Danish counterpart admitted Huawei’s possible involvement in the country’s 5G network is now of interest to the security organs, explicitly referring to “the dynamics between companies in China and the Chinese state”.

Perhaps most dramatically, Huawei’s CFO Meng Wanzhou 孟晚舟, who happens to be the daughter of the company’s founder, was arrested in Canada on Dec 1 at the request of the US. An extradition battle is now being fought at Canadian courts, with the stakes illustrated by PRC’s counter-move – the arrest of at least two Canadian citizens in China in what looks like preemptive hostage-taking. The current climate extends those concerns to a third case, and has lent media interest to the cases of several “forgotten” Canadian victims of politically motivated arrests in China, notably of Chinese or Uyghur ethnicity. Some of these cases feature the increasingly extraterritorial application of the PRC’s repression apparatus, with abductions outside the PRC’s jurisdiction and the unlawful treatment of foreigners of Chinese origin as PRC nationals—two characteristics illustrated in the case of Swedish editor Gui Minhai 桂民海, recently discussed on Sinopsis.

Huawei’s CEE front: the case of Poland

Given the very public concern about Huawei in Five Eyes countries, there isn’t much the PRC can do to counter the procurement bans there. Just like in the trade war, much of the battle is therefore taken to third countries, especially those cultivated by China recently through the BRI and related activities. The countries in former Soviet-bloc Eastern Europe targeted in the PRC’s “16+1” initiative are one of the hottest battlegrounds, sitting as it were on two chairs that keep pulling further apart: the EU and NATO memberships, actual or desired, on one side, and the “special relationships” with the PRC on the other.

The Czech warning is particularly significant as it risks setting in motion a domino effect in other Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, an important market for Huawei.

Contagion to Poland, the largest country in the region, would be especially damaging. Huawei’s Polish foray has been particularly successful. The Polish government has remained silent on the security implications of the use of Huawei products. Huawei’s way to the Polish 5G network seems unimpeded: while its French parent declines to use Huawei equipment at home, Orange Poland has begun 5G tests in partnership with Huawei. Last month, Huawei co-sponsored and took part in a debate on artificial intelligence organised by the Polish state news agency and featuring two ministers.

Recent developments show Poland’s significance within the CCP’s discourse management activities. Official caution towards the PRC has become pronounced, with PM Mateusz Morawiecki’s recent call to “maintain the proper level of deterrence, not against the forces of the free world, but against China and Russia” and, not two weeks ago, a MFA statement on industrial cyber-espionage attributed to China. Efforts to create a more friendly image of the CCP are illustrated in a full-page advert praising Xi Jinping in Poland’s leading centre-right daily, paid by an entity the paper has refused to identify. Huawei’s link to the CCP’s broader propaganda and influence efforts can be seen in the fact that one of the company’s Polish interlocutors is a senior target of elite “friendly contact”.

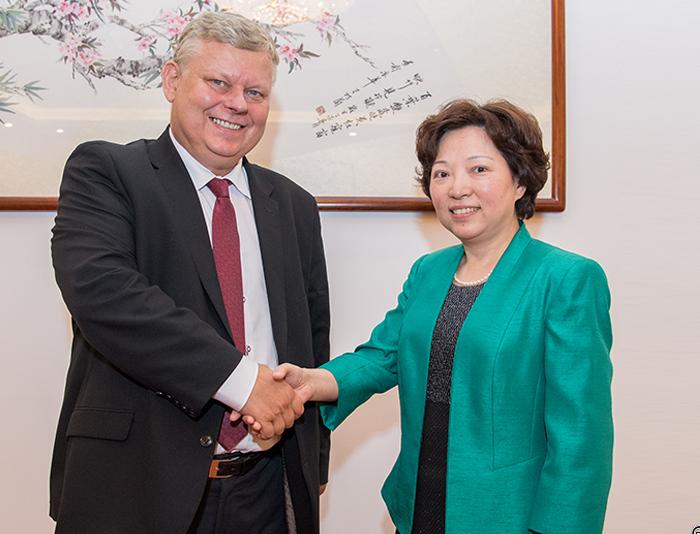

It was Marek Suski, the head of the PM’s cabinet, who announced last month after talks with Huawei in Shanghai that the company planned to invest in a research and development center near Warsaw. Suski is a preferred interlocutor of the CCP International Liaison Department (ILD), the organ whose ‘party-to-Party’ purview has been extended from fellow Communist parties to embrace the ‘bourgeois’ spectrum in a form of United Front work that targets foreign politicians.

At a meeting with ILD deputy head Shen Beili 沈蓓莉 in October last year, Suski congratulated the CCP on the occasion of its 19th Congress and stated his party’s willingness to use the “joint construction of the Belt and Road” as an opportunity for cooperation. Last May, Suski made news in the country after a Polish journalist spotted him at an ILD-organised ‘dialogue with world parties’ event in Shenzhen. As Sinologist Katarzyna Sarek commented soon after the event, it was remarkable for Suski, a member of the ostensibly anti-Communist ruling Law and Justice party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS), to attend an event glorifying a ruling Communist party simultaneously with the celebration of Marx’s 200th anniversary (notably graced by a politician registered as an agent of the Czechoslovak secret police). To further illustrate the irony, in the very same month, the PiS government had to apologise after the police showed up at an academic conference on Marxism to establish whether a crime of propagating totalitarianism had been committed.

Friends on demand

Given the stakes, it’s hardly surprising the NÚKIB public warning against Huawei in the Czech Republic immediately led to a diplomatic showdown. In the Chinese press, the Huawei “ban” in the CR is portrayed as a litmus test of the company’s future in the “vast majority of countries in the World” (outside of the Five Eyes alliance). The CR is also relatively easy to put pressure upon, given the “elite capture” systematically performed in the last five years by, among others, the notorious CEFC conglomerate, one of whose top representatives, Patrick Ho (何志平), has just been convicted at a federal court in Manhattan on seven counts related to large-scale corruption involving senior UN officials and African politicians. Ho’s direct superior, (former) CEFC chairman Ye Jianming 叶简明, remains an official advisor to President Miloš Zeman, the most openly pro-Beijing Czech politician, despite being held for almost a year incommunicado in China by the CCP’s disciplinary organs.

Huawei has a history of employing ‘friendly contact’ and the recruitment of foreign figures for its PR efforts, intended to deflect attention from its background and practices and present itself as a ‘normal’ private company. As an high-profile entity linked to the Party-state-Army and enjoying its support, Huawei has used methods typical of the Party-state’s liaison and United Front activities, including ‘localised’ interactions targeting governments and academia. As the recent Czech developments illustrate, these efforts enjoy the backing of the PRC propaganda machine.

Despite the national ban, Huawei has continued to bid in Australia at the state level, notably winning a contract to build a railway mobile data network in Western Australia, ignoring security warnings. Years earlier, a minister involved in negotiating the deal had benefited from Huawei’s generosity during a China trip to get “an insight into Huawei’s operations”, partially paid by the company; the WA ruling party’s links with United Front figures have continued to emerge.

In New Zealand, a country noted for the degree of influence the CCP has achieved in local politics through years of United Front work, politicians have been particularly supportive of the company. Huawei has used the example of New Zealand’s “embrace” of Huawei “within their own security frameworks” in PR campaigns meant to assuage security fears. Former prime minister John Key’s support for Huawei goes back to 2010, when he personally announced its possible involvement in a broadband bid. Key defended Huawei in parliament in 2012, reportedly disagreeing with security agency warnings. Key’s “support” for Huawei, contrasting with Australia’s concerns, was recognised by PRC state media. The previous government lauded a Huawei investment last year. The current Labour-led government, which continues to refuse to address evidence of CCP influence activities in the country, reportedly hesitated before naming the PRC as the author of a global IP theft campaign. After the warning against Huawei 5G technology, the minister responsible for the intelligence services rushed to deny it was a “ban” against “a particular company or a particular country”.

Huawei has sponsored work praising its technology by the Brookings Institution, a US think tank.

Friendly ties and the state’s support for Huawei became activated as the company faced an unfavorable climate in the West. Notably, Jeffrey Sachs, an economist, published an op-ed attacking the US over the arrest of Meng Wanzhou. Challenged on Twitter, Sachs, a special advisor to the UN secretary general on sustainable development, praised “the many benefits of Huawei technologies for sustainable development” while denying he was aware of the Xi’s Xinjiang internment camps. Sachs had stated similar praise for Huawei in his foreword to a Huawei promotional brochure. Unusually for a Twitter discussion, the one involving Sachs motivated a condemnation from the Global Times.

Sachs is, in fact, linked to the efforts to install CCP discourse at the UN, recently covered on Sinopsis. As Inner City Press has noted, Sachs has been listed as an “advisor” in CEFC materials. For at least three years, he spoke at CEFC events featuring Patrick Ho, still at large, where he praised the agreement between CCP initiatives and the UN sustainable development goals. Crucially, Sachs has sat on the advisory board of former UN general assembly president Vuk Jeremić’s think tank CIRSD since its establishment in 2013. Jeremić is another of the UN officials Patrick Ho cultivated: he became a CEFC “consultant” right after leaving his post, and was paid hundreds of thousands to “open doors” for CEFC. Even though CEFC has been neutralised by the fall of Ho and Ye, CIRSD is among the organisations still active in the discourse engineering enterprise, which perhaps motivated the Chinese state-media intervention over a social media conversation. Sachs deleted his quarter-million follower Twitter account soon after these links were exposed.

Showdown in Prague

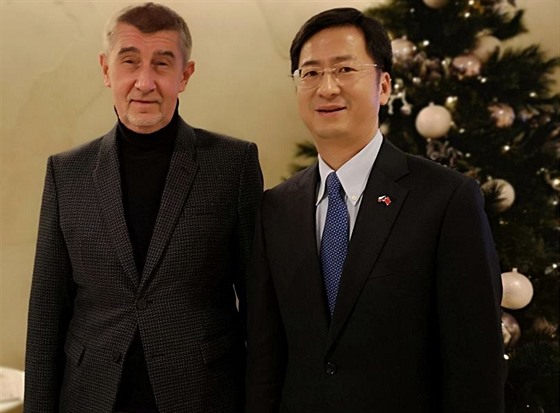

In the Czech Republic, the PRC has many “friendly contacts” to call upon. Unusually for the pre-holiday season, it only took four days after the NÚKIB warning for PM Andrej Babiš to convene the State Security Council (Bezpečnostní rada státu, BRS), a rather toothless government body, to urgently discuss the “ban”. PM Babiš has been much weakened by recent scandals around the apparent abuse of EU subsidies for his business conglomerate. In the state of almost permanent government crisis since the last elections more than a year ago, he is much dependent on political support from President Zeman. His minority government also needs the parliamentary support of the Communist party (Komunistická strana Čech a Moravy, KSČM). Zeman and the KSČM are among the most staunchly pro-CCP voices in the country.

The BRS issued a pithy statement emphasising, apparently for Chinese ears, the obvious fact that NÚKIB is independent of the government, which cannot make it revoke or revise its warnings. Among a series of brief paragraphs stating the obvious, one stands out: that the agency is not qualified to comment on the international situation or on other states’ legal arrangements. Since the main public justification for the NÚKIB warning was the legal requirement for PRC citizens and companies to assist in intelligence gathering when called upon, such statement sounds like an indirect rebuke to the document.

More importantly, the PRC side staged a peculiar diplomatic ritual when it forced a meeting between the Babiš and the ambassador in Prague, Zhang Jianmin 张建敏, on the rather undiplomatic date of Sunday, 23 December. The meeting was not reported by the government through the usual channels, but only by the embassy, on its website (Chinese, Czech) and in a Facebook post. The embassy’s account of the meeting makes Babiš appear as doing a full turn-around on the Huawei issue. He supposedly called the NÚKIB warning “a hasty decision”, caused by “a misleading warning”. The post then employs some rather arrogant language:

Ambassador Zhang pointed out that the warning issued by a Czech agency, which is not at all grounded on reality, had had a detrimental impact and the Chinese side resolutely protests against it. He said that the Chinese side acknowledges the Czech government’s effort to rectify the relevant mistakes and hopes that the Czech side adopts effective measures to prevent such events in the future and to effectively protect the legitimate rights and interests of Chinese firms.

The language did not go down well with the Czech public, already quite sensitive to Chinese activities in the country and the unconditional support it receives from part of the political establishment. Despite the holiday season, the FB post already generated a lot of discussion on social media, mostly highly critical. The opposition was quick to seize on it, with politicians variously stating that the Czech Republic has fallen “in the hands of servile collaborators with undemocratic powers” or that the PM’s reversal at “a meeting with representatives of a country that threatens” the country’s information security meant he was “escaping his responsibility” to protect it.

Such undiplomatic language, guaranteed to further undermine the PRC image in the Czech Republic, was more likely intended for international audiences, amplified through state media. The heavy-handed response by the PRC embassy seems intended to preempt a replicating effect in the region and beyond, where a similar debate about Huawei is likely to take place sooner or later.

The immediate propaganda reaction further cements the idea that the Babiš administration’s attempt to contain the effects of the NÚKIB warning followed coordinated PRC pressure. One day after the BRS statement, a story by Xinhua’s senior Prague correspondent declared the Czech government had “corrected its mistake” on Huawei. The story soon made it to the English-language Global Times, in the sloppy English characteristic of stories pushed by higher-ups in propaganda organs.

After the backlash over Christmas, Babiš resurfaced to refute the embassy’s account of the meeting.

The Chinese ambassador commented in an unusual and public way about a meeting he had urgently requested, where he stated the Chinese side’s position in a very non-standard way.

Babiš explicitly denied that the government had made a “mistake” with the intelligence warning, as PRC state media had proclaimed: “I don’t know what the ambassador is talking about”, he said, adding that “the government takes the NÚKIB’s warning seriously”. The Czech-language statement is, however, unlikely to reach the Chinese public or the larger audience targeted by the PRC external propaganda organs. The goal of ‘killing the chicken to scare the monkeys’ remains feasible, despite Babiš’ newfound sovereign zeal.

“Friendly contact” conquers all

The Party-state’s efforts to protect Huawei, from friendly op-eds to the Christmas démarche in Prague, show the usefulness of the long-term build-up of influence work. Even countries of less immediate international significance can become key assets: at a critical juncture for a ‘national champion’ desperate to keep the CEE market, politicians and commentators who have developed pro-CCP positions can be called in its defence. With a quick coordinated reaction between Xinhua and the embassy, the propaganda battle being waged in Prague can resonate throughout the region and beyond.

The PRC’s leverage over the Czech Republic, a country where its FDI has been negligible, ultimately reveals various forms of ‘liaison’ and United Front work as cheaper and more effective tools of foreign policy than trade and investment.

With thanks to Anne-Marie Brady and Geoff Wade