The PRC’s involvement in UN affairs has been on the rise in recent years. It has become one of the largest contributors to the organisation, in terms of both funds and soldiers. Now it wants influence.

True to its attention to propaganda, the CCP has made it a major goal of its UN work to maximise its ‘discursive power’ at the organisation, seeking to redefine ‘human rights’ and get Xi Jinping’s pet initiatives institutionally endorsed by an international body. These goals, repeatedly stated by authoritative sources, are being pursued through both diplomacy and other means.

Specialised CCP organs like the United Front Work Department and party-linked entities like CEFC employ some unorthodox tactics. These tactics, including elite capture and bribery, are applied both locally in vulnerable countries, and globally at the world’s foremost multilateral body. Some actors flawlessly span the whole range from individual East European and African states all the way to top UN officials. Evidence from recent court cases suggests a pattern of global interference combining both local and global “political work”.

The UN talks the Xi-Talk

Growing Chinese influence has made UN officials more and more willing to explicitly support the CCP’s political, economic and purely propagandistic projects. The PRC has managed to pass two resolutions at the Human Rights Council (HRC). The most recent one, in March, promoted “mutually beneficial cooperation in the field of human rights” together with such illustrious champions of said field as Eritrea, Cuba, Syria and Venezuela. The first resolution invoked a favourite concept of Xi Jinping’s, the “community of shared future”, thus officially making Xi-speak (习语) part of the UN lingo.

Controlling discourse at the UN human-rights system has been a priority for the CCP since the PR-debacle it suffered post-Tian’anmen. Tactics to impose “human rights with Chinese characteristics” have ranged from usual diplomacy to more characteristic intimidation. A central goal is to obstruct the work of NGOs within the UN system, embedding the CCP’s abhorrence of civil society into a new global ‘human-rights’ normal.

In what a former HRC special rapporteur has called a “Trojan horse”, the vague ‘win-win’ language in the UN resolutions channels a state-centric approach that sees human rights as primarily the rights of rulers. Not long ago, the CCP had to rely on a few bizarre characters to promote its ‘human rights’ redefinition: from Tom Zwart, a Dutch academic who finds talk of repression “unfair to the progress in human rights under Xi”, to a mysterious “Human Rights Co., Ltd” of New South Wales. The HRC is now part of that club and this language infiltrates its resolutions. The US withdrawal from the Council will further accelerate this process.

Xi Jinping’s ‘discursive power (话语权)’ isn’t limited to the human-rights system. International endorsements of Xi’s pet ‘Belt and Road’ initiative (BRI) are a major goal of propaganda efforts involving media, domestic and foreign like-minded think tanks, and various multilateral organisations. “Multilateralist” language has indeed been recognised as a tool to “dispel misgivings” about Xi’s geopolitical project. When conducting “external propaganda [对外宣传, exoprop]”, instead of haranguing countries to “participate in the construction of the ‘Belt and Road’”, implying a leading role for China, one should call for countries to “cooperate” in such construction: with China, but also “with each other, multilaterally”. China’s Belt and Road should not be called “China’s Belt and Road”; “let us stress ‘us’, not ‘me’”. The predilection for the term ‘initiative’ over ‘strategy’ in external propaganda reflects this: although we don’t deny that the Belt and Road is part of the national strategy, when “propagandising and explaining it” abroad we can’t call it “a national strategy led by one country”: “would a country want to participate in another’s national strategy?” In this quest for multilateral-sounding backing, the UN was the big prize.

Discourse management at the UNDP

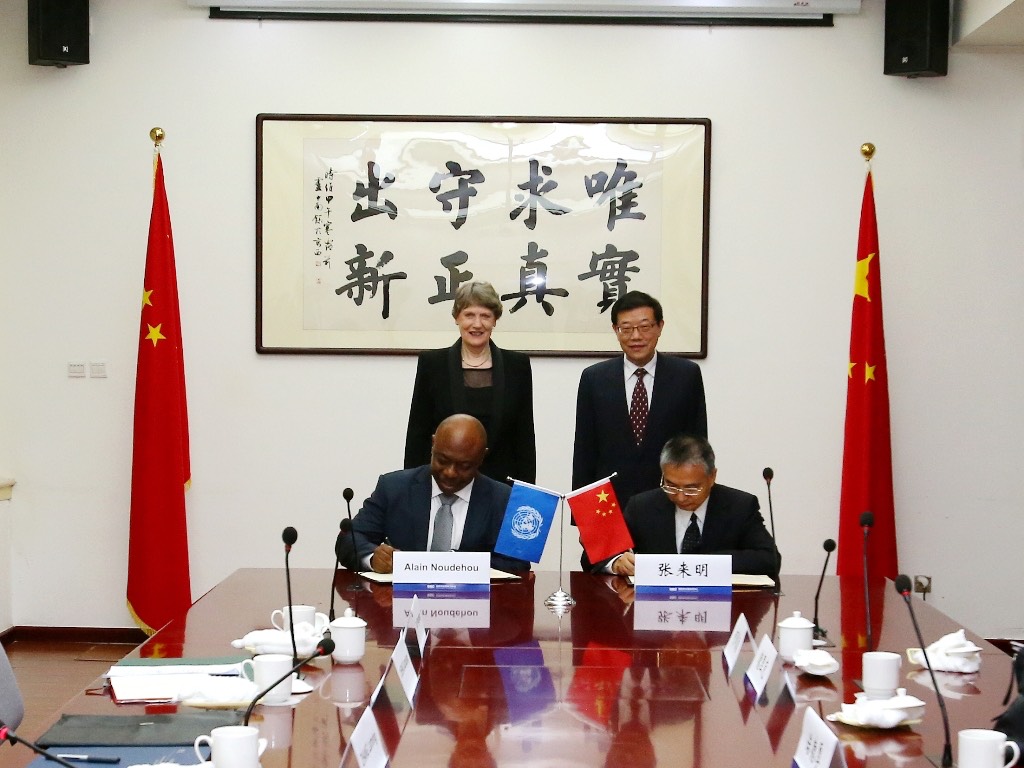

The UN Development Programme (UNDP) provided a suitable avenue. In early 2015, in a journal under the State Council Development Research Center (DRC, 国务院发展研究中心), Wang Yiwei 王义桅, a senior BRI-proselytising academic with his own column on the CCP News website, advocated “integrating the Belt and Road into the [UNDP] Post-2015 Sustainable Development Agenda, implementing the 18th Party Congress ‘Five-in-One’ [五位一体] concept” and “building a green Silk Road”. Propaganda portal Zhongguo wang 中国网 reposted Wang’s article on 4 May, coinciding with a Beijing visit by the head of the UNDP, former New Zealand prime minister Helen Clark. Talking to state media, Clark was at that point still non- committal about BRI. She was more receptive towards efforts to associate BRI with the UNDP 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Less than a month after the Agenda’s adoption, she told Xi and others in Beijing that China’s “commitment” to his BRI project helped make the country “a major contributor to development co-operation”.

On the same trip, she had a chance to discuss BRI and an attendant discourse-management endeavour, the Silk Road Think-Tank Network (丝路国际智库网络), at the signature of an agreement with the DRC. By early 2016, an SIIS paper was already celebrating the expected propaganda milestone: the convergence between BRI and the Sustainable Development Agenda “helps China obtain more discursive power and influence within the new international system of development governance and even the entire global governance architecture.” Mid-year, Xi himself linked BRI to the Agenda at a meeting with secretary general Ban Ki-moon. The Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), a UN department described by a European diplomat as “a Chinese enterprise”, endorsed the BRI-Agenda link in a study commissioned by the PRC State Information Center (SIC, 国家信息中心) and written by a DESA employee who began his career at the SIC’s predecessor entity.

In September, now campaigning for UN secretary general, Clark signed a memorandum with the National Development and Reform Commission “to enhance collaboration” for the “implementation” of BRI and the Agenda, this time literally pledging the organisation’s “support for the Belt and Road Initiative”. Clark praised Xi’s Initiative, a “powerful platform” that “can serve as an important catalyst and accelerator for the sustainable development goals”. Clark would later deny any connection between her support for BRI and her campaign for the top UN job, during which her successor as New Zealand prime minister helpfully opined she was “recognised as a friend of China”. She lost (ironically blocked by, among others, China), but the winner, António Guterres, endorsed BRI at the 2017 Belt and Road Forum in Beijing. Post-Clark, UNDP has preserved her Xiist legacy.

Guterres’ promotion of BRI as a useful tool to fight poverty blissfully disregards multiple studies warning that the Initiative can lead poor countries into a “debt trap”. Perhaps the same logic lies behind his praise for the PRC’s diplomatic efforts in solving the Korean crisis, despite its violation of UN sanctions by shipping oil to North Korea.

CEFC at work locally and globally

The CCP presumably owes these propaganda victories at the UN to good old diplomatic horse trading, sheer economic size and some harassment. But its growing influence has also been accompanied by a striking, unprecedented phenomenon: a series of corruption scandals reaching to the top levels of the organisation. Surfacing cases of bribery raise suspicions that China is effectively buying the UN, top down.

This approach appears to mirror at a global level the PRC’s tactics in its bilateral relationships with individual states, especially the more vulnerable ones in Africa, Latin America, SE Asia and Eastern Europe. “Elite capture” in many of these countries has been accompanied by reports of and court indictments for outright corruption at the highest political level. Moreover, reported cases of global and local corruption intertwine, linked by specific actors operating both at the level of nation states and the UN system. Among these, perhaps the most curious is a mysterious Chinese conglomerate called CEFC. Various parts of the company have been connected with elite capture in Eastern Europe, top-level political corruption in Africa, and bribery at the UN headquarters in New York.

The director of CEFC’s non-profit subsidiary, former Hong Kong official Patrick Ho (何志平), was indicted last year in the US, accused of bribing several African politicians, including Ugandan foreign minister Sam Kutesa, former president of the UN General Assembly (UNGA). Coinciding with his arrest, CEFC donated 1 million USD to the UN Department for Economic and Social Affairs (DESA, the UN organ described as “a Chinese enterprise”). Just a day after Ho’s arrest, both the UN secretary general and UNGA president excused themselves from attending the ceremony to award a $1m DESA grant with “funding support” from CEFC. But DESA still kept the money.

According to the indictment, Patrick Ho had 500 000 USD wired to an account chosen by Kutesa, months after making CEFC chairman Ye Jianming, Ho’s boss, his “special honorary advisor” as UNGA president. (Kutesa denies the allegation.) Ho has been quoted as claiming that the case is not just against him, but against CEFC and the Belt and Road.

Earlier that year, in April 2015, Ye had been appointed “economic advisor” to Czech president Miloš Zeman. (Except for one news item on the Chinese internet, Ye’s Czech appointment would remain unreported until September that year.) Ye Jianming is currently being held by the Chinese authorities at an unknown location.

Serial Corruption at UNGA

Remarkably, these accusations against CEFC are already the second case of a UNGA’s president bribed by Chinese entities. Last May, Macau tycoon Ng Lap Seng 吴立胜 was sentenced to 4 years in prison for bribing Kutesa’s predecessor as UNGA president, the Antiguan John Ashe, and a Dominican deputy ambassador to the UN, Francis Lorenzo. The indictment claimed that Ng spent more than $1.3m to get the UN to support the construction of a large UN conference centre in Macau; in exchange for bribe money, Ashe and Lorenzo submitted to the UN secretary general a document stating that the conference centre would “support the UN’s global development goals”. In other words, Ng’s bribery had similar goals to those pursued by the PRC through usual diplomatic channels (with the addition of direct profit for Ng’s company). Ashe died while awaiting trial. Ng claimed the case was politically motivated. He was found guilty on all counts.

At the time he bribed Ashe and Lorenzo, Ng was a sitting member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), an advisory body part the United Front system that did not expel him despite his arrest. He was not reappointed last January.

CEFC also interacted with Ashe. In 2014, DESA and CEFC’s think tank co-organised an event about China’s urbanisation plans, with PRC academics as speakers, Patrick Ho as moderator and Ashe as “officiating guest”. An announcement for the event published by DESA, written in a style somewhat resembling Ho’s own, asserts CEFC’s dedication to “the post-2015 development goals”. The event was hailed by PRC state media. Not three months earlier, Ashe had attended a CEFC-organised “Luncheon talk” in Hong Kong, where he delivered a speech titled “The Post-2015 Development Agenda: Setting the Stage!”.

CEFC has also cultivated Ashe’s predecessor, Vuk Jeremić, former Serbian minister of foreign affairs. After he left office in 2013, the Chinese company hired him as a consultant. His cooperation with CEFC included “[d]iscussing […] China and the New Silk Road” with Patrick Ho, who lectured at Jeremić’s think tank on BRI and the UN Post-2015 Development Agenda. Jeremić also moderated a CEFC event with Wang Yiwei, the BRI-UN harmonisation advocate cited above, and a Silk and Road forum with DRC director Li Wei as keynote speaker. Serbian media claim CEFC has donated money to Jeremić’s think tank.

The Australian connection

Two consecutive UNGA presidents being bribed is hardly a coincidence. Moreover, the Ashe and Kutesa cases are personally linked: Kutesa’s wife was a board member at the Global Sustainable Development Foundation, an organisation used by Sheri Yan, the “Queen of the Australia-China social scene”, to bribe Ashe “in exchange for official actions […] to benefit several Chinese businessmen”. The arrangement, which began before Ashe’s presidency, and continued through and after it, involved Ashe’s appointment as (remunerated) “honorary chairman” of the Foundation and its later reincarnation, the Global Sustainability Foundation. She pled guilty in 2016 and was handed a 20-month sentence.

In China, Yan’s Foundation enjoyed a disproportionate degree of access given its novelty and vacuity. Two months before Yan’s arrest, Chinese media reported, the Foundation bestowed an appointment to a former Shenzhen propaganda chief and counsellor to the State Council at no less a venue than the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse. Sheri Yan was there, accompanying not Ashe but his successor Kutesa. Yan has used her CCP connections to facilitate Australian access in China, and, allegedly, vice versa: an Australian media investigation claims she “introduced an alleged Chinese spy to her Australian contacts”.

Yan’s Ashe-pampering included arranging for the dignitary to attend a private conference in his official capacity, hosted by “a real-estate developer” whom the indictment names only as “C[o-]C[onspirator]-3”, who was not himself charged. “One of [CC-3]’s companies” paid Ashe a $200k fee for his attendance. Although it doesn’t name him, the indictment (p. 33 ff.) provides sufficient information to identify CC-3. As open, authoritative sources show, the date for the conference (17 Nov 2013), where Ashe “gave a speech”, points to the event held at a venue provided by Kingold Group (侨鑫集团), owned by Chinese-Australian billionaire Chau Chak Wing 周泽荣. Its official agenda, in Chinese and English, shows both Ashe and Chau spoke at the event; the official Kingold website also bilingually summarises his speech. The event was widely reported online by state media, in Chinese (CCP News) and English (China Daily). In short, if the quotes in the US indictment are correct, CC-3 is indeed Chau.

Chau has sued local journalist John Garnaut for defamation over a piece that reached similar conclusions. Based on the reasoning above, however, Chau’s identification, which Garnaut claims to have confirmed with additional sources, can only be called solid journalism. Moreover, Andrew Hastie, chairman of the Australian parliament’s joint intelligence and security committee, recently confirmed he had learnt “from US authorities” that CC-3 is Chau, and that he had not been indicted for “reasons that are best not disclosed”. Chau, whose links to the links to the United Front system are well-documented, has generously donated to both sides of Australian politics, as well as to various causes.

As quoted in the US indictment, “CC-3” seemed to share the PRC’s interest in UN affairs: Ashe’s “sincere friend” in Guangdong “has the pleasure to offer you a permanent convention venue for the UN meetings on the sustainability and climate changes [sic] in the efforts to fully realize the Millennium Development Goals.”

New world a-comin’…

Despite charges of high-level bribery, the non-profit subsidiary of CEFC, China Energy Fund Committee, 中华能源基金委员会), still holds the title of special consultant to the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations (ECOSOC), whose current chair is Czech diplomat Marie Chatardová.

Czech President Zeman has supported Chatarodová both for the ECOSOC position and as possible minister for minister of foreign affairs in discussions on cabinet formation. Zeman, known for his pro-Beijing stance, has not dismissed his own honorary advisor, the ex-chairman of CEFC, Ye Jianming, who is now detained by the Chinese authorities at an unknown location. Similarly, the non-profit wing of CEFC remains in ECOSOC even as its leader Patrick Ho lingers in US custody on corruption charges.

Chatardová and other high-ranking UN officials had been declining to comment on the situation despite repeated requests from Inner City Press, a project specialised in investigative journalism within international institutions such as the UN or the World Bank.

After repeated inquiries from both Inner City Press and Czech media, the UN finally released a statement on June 5 explaining that Chatardová could not have done anything to dismiss CEFC, as that power lies with member states. Further communication with the Czech mission at the UN clarified that the corruption charges against one of their associates have not even been discussed at ECOSOC. The only official body interested in the corruption at the top of the UN seems to be the FBI.

It is hard not to see a connection between the corruption cases in the United Nations and the rise of China’s “discursive power” in the organisation. As top UN officials get arrested for corruption by Chinese actors, the global body increasingly adopts Beijing’s narrative on a new “Globalisation 2.0”, epitomised by the Belt and Road Initiative. The strange happenings at the UN could indeed offer glimpses of this new world coming.