This policy brief is also available for download.

Executive summary

The People’s Republic of China has a unique political system that combines the basic Leninist concept of the Party-state (党国一体) with elements adopted, and adapted, from modern capitalism. It has been experimenting in the controlled environment of one-party rule with borrowed mechanisms like (“socialist”) market forces or a specific application of the rule of law – more appropriately translated from the actual Chinese term as “rule by law” (依法治国).

This hybrid system is not always well understood in Europe, which tends to see China through the prism of its own political and economic practice. Seemingly familiar phenomena get mentally translated into their Western equivalents, such as private enterprise or market competition. However, this surface equivalence is often imperfect, and sometimes outright misleading. The proverbial attributive “with Chinese characteristics” (有中国特色的), added to familiar terms, may denote a radically altered reality. The fundamentally different political systems make for many quite consequential faux amis.

One such false friend is the notion of “economic diplomacy”. The proactive foreign policy of Xi Jinping’s “New Era” finds its rhetorical expression in economic terms, as exemplified in initiatives like the ‘Belt and Road’ or ‘16+1’. Yet the net impact of these initiatives often tends to be political rather than economic. In the PRC, politics is “in command”, and the relationship between politics and economics is more intricate than generally acknowledged.

In this policy brief, based on extensive research of original sources in Chinese and local languages, we use the examples of the Czech Republic and Central and Eastern Europe to demonstrate that China’s “economic diplomacy”, while often bringing little economic effect, provides rhetorical cover for the extensive capture of local political elites through “friendly contacts” and targeted corruption.

We map the effects of such elite capture through recent controversies surrounding two Chinese firms, CEFC and Huawei. In the policy recommendations, we stress the need to resolve through effective conflict-of-interest legislation the potential conflicts of interest of current and former politicians employed, or otherwise economically engaged, by Chinese companies. We also call for more effort to study and explain to all stakeholders the fundamentals of the PRC’s unique political and economic systems, and their implications for informed policy-making.

Contents

- 1 Economic diplomacy, propaganda and political influence

- 2 Forty years of PRC economic diplomacy: From know-how transfer to political interference

- 3 16+1 as a spatial and political construct

- 4 The Czech Republic: ‘Economic diplomacy’ as a byword for elite capture

- 5 The Huawei affair: Weaponising friendly contacts in times of crisis

- Policy recommendations

Economic diplomacy, propaganda and political influence

The sheer size of its economy makes the People’s Republic of China (PRC) important as a trading partner and potential source of investment for many EU member states. It is also a world power with a radically different political and value system pursuing an increasingly ambitious foreign-policy agenda. Advancing common European interests and those of individual member states in this complex relationship demands coordinated policies informed by a deeper understanding of China’s political, economic and foreign-policy priorities.

The PRC’s unique political system, led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), must be understood on its own terms rather than as an extrapolated version of familiar Western concepts. CCP Secretary General Xi Jinping’s renewed stress on Party supremacy and an increasingly expansive foreign policy agenda have made the CCP’s external propaganda and political influence work central to its interactions with entities abroad. These concepts are essential for understanding Party-led ‘economic diplomacy’ on the Party’s terms, avoiding Western faux amis.

Propaganda (宣传), in the Leninist tradition a term free from the negative connotations attached to it in the West, aims not to convince, but to instill ideological constructs through discourse management, at the expense of competing ideas blocked by censorship.2 External propaganda (外宣), aimed at foreigners on a global scale, has at its disposal a well-developed system of methods and organisations at home and abroad.3

In its efforts to manage external interactions, the CCP often relies on third parties engaged through the tactic known as United Front work (统一战线工作). Like propaganda, United Front work is “a task of the whole Party”,4 and is supported by an extensive organisational system that branches down from the national to the provincial, city and district levels of administration and manages a whole network of related organisations overseas.5

The United Front tactics used by the CCP, seeking to coopt extra-Party forces at home and abroad, trace their roots to the Comintern, which brought them to China in the early 1920s. In post-War Europe, they were notably implemented to control vestigial non-Communist parties and other organisations in the ‘National Fronts’ in the Soviet bloc, as they were in Communist East Asia.6 Xi Jinping’s administration is upgrading the CCP’s United Front toolbox to work in the international domain. Organisations within the CCP’s United Front system that once targeted domestic and diasporic extra-Party forces now help the CCP exert its influence on foreign mainstream politicians. The phenomenon has been best described in New Zealand and Australia,7 where it has prompted a legislative response, but is also being documented in Europe.8 Another Party organ whose remit is expanding to serve as a tool of international United Front work is the CCP’s International Liaison Department (ILD). The ILD is active in forming a global CCP-led ‘consensus’ increasingly embraced by many mainstream political parties abroad, as demonstrated by the 2017 world summit (“dialogue”) of such parties in Beijing.9

Beyond the PRC Party-state-military system, ostensibly private companies linked to the CCP and dependent on its support can also be instrumentalised as policy tools, adding the market as a fourth key component of the CCP-led Leninist order. CEFC, a company that contributed to the CCP’s global discourse-management and political-influence activities with methods ranging from “friendly contact” to high-level corruption, has been found to be linked to the PLA’s “political warfare” apparatus.10 Huawei, a ‘national champion’ whose defence against security concerns abroad has mobilised major resources of the Party-state, collaborates with the PRC repression machine, notably in Xinjiang. Its surveillance technology is exported abroad through concepts like smart and “safe”-city technology.11

The combined effort by Party-state and nominally private actors has the potential to undermine the integrity of democratic systems. Various forms of United Front and “liaison” work aimed at coopting foreign decision and opinion-makers as the CCP’s “foreign friends” can eventually lead to the capture of the elites of foreign states. Captured elites may then act to amplify the CCP propaganda messaging, effectively repurposing basic democratic institutions as tools of foreign influence. Recent developments in the Czech Republic, discussed below, illustrate some of these mechanisms, but they have been documented in other states as well.12

The CCP’s United Front and propaganda work, both pervading Party and state activity, are facilitated by a high degree of knowledge asymmetry between the PRC and its foreign interlocutors. The paucity of policy-relevant research informed by an analysis of the recent evolution of the PRC political system available to European decision makers, especially at the local level, contrasts with the highly coordinated propaganda activities of entities under various degrees of CCP influence or control. This allows for the relatively successful instillation of CCP propaganda memes, from “economic diplomacy” as a rhetorical cover for political influence to the “multilateralism” that supposedly underlies various Beijing-centred geopolitical initiatives (“Belt and Road”, “16+1”).13

Forty years of PRC economic diplomacy: From know-how transfer to political interference

Economic diplomacy has been a major foreign policy tool of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) ever since the beginning of the policy of “Reform and Opening” (改革开放) initiated in late 1978 by Deng Xiaoping. The very purpose of that policy was to catch up with the outside world by introducing foreign know-how to China. The actual forms of China’s economic diplomacy as a foreign-policy tool underwent major shifts during these forty years. The three decades defined by Deng Xiaoping’s cautious foreign policy contrast with the more assertive stance in the last ten years, and especially with Xi Jinpings’s robust approach since 2012.14

Hiding your shine, biding your time: Deng Xiaoping and his immediate successors (1978 – 2012)

In the first 30 years of “Reform and Opening”, the PRC’s economic diplomacy largely consisted of enticing foreign businesses to open shop in China and share their know-how through joint ventures with local partners. At the same time, China protected its domestic market with tariff and non-tariff instruments while enjoying full access to globalised world markets.

These mercantilist policies were expected to be phased out once China’s economy became more competitive, especially after the PRC joined the WTO in late 2001. Similarly, there was a widespread consensus that closer integration into the global economy would lead to China becoming a “responsible stakeholder” in the liberal world order.15 Some observers expected a process of “convergence” with the prevailing model of democratic capitalism, even though such a notion has long been explicitly anathema to the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

In the last decade since the 2008 global financial crisis, it became clear that such optimistic scenarios would not be borne out. In fact, the opposite happened: the PRC started to employ its growing economic and political clout not to “converge” towards liberal capitalism, but rather to undermine it in favour of its own model of (Party-)state capitalism. With the crisis of confidence in the liberal order after the 2008 financial meltdown, the PRC alternative grew in relative allure.

Correspondingly, the PRC’s economic diplomacy grew more assertive after 2008. It began using access to the Chinese market more directly as a coercive tool with various unofficial boycotts targeting individual foreign companies or even entire states. In 2010, China effectively denied Japan access to its rare earth exports, a necessary component in several high-tech industries.16 In 2012, an illegal-fishing incident off Scarborough Shoal led to a large-scale trade confrontation between the Philippines and the PRC, complete with the deployment of gunboats and subsequent Chinese occupation of the disputed area.17 Unofficial boycotts have proliferated since then, including a comprehensive boycott of all things South Korean in 2017 in response to the deployment of the THAAD missile system.18 This boycott also introduced a new-coercive element to China’s economic diplomacy toolbox: weaponising tourism by cutting off the inflow of Mainland Chinese tourists to target countries. By 2018, the PRC’s coercion succeeded in forcing various foreign entities, notably airlines, to endorse its territorial claims over Taiwan.19

The newly assertive application of economic diplomacy further escalated with the ascendency of the current CCP Secretary General and PRC President Xi Jinping in 2012 – 2013. Apart from abolishing term limits for himself, Xi Jinping also declared his own “New Era” (新时代), defined, among other things, by the “window of historic opportunity” for China to move towards the centre of the world stage.20

Xi Jinping’s “New Era” of “historic opportunity” (2012 – present)

Xi’s “New Era” marks the end of Deng Xiaoping’s cautious foreign policy of “hiding one’s shine, biding one’s time”, formulated in 1989 in the aftermath of the international censure after the Tian’anmen massacre.21 Especially after the election of President Trump and the ensuing tensions in Western alliances, there was an apparent sense of triumphalism in Beijing. In early 2017, Xi Jinping introduced a new slogan, “Two guidances” (两个引导), to sum up the new conditions: in the New Era, the PRC was to “guide” the new wave of globalisation (Globalisation 2.0) and the global security architecture.22 (The slogan has since been deemphasised, together with several other seemingly too provocative initiatives, such as “Made in China 2025”.)

In the New Era, Chinese economic diplomacy evolved from a tool for know-how transfer into a tool of political influence and interference. The PRC is now increasingly deploying its economic clout to reshape the post-War international order. The most striking expression of this effort is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI, 一带一路), the signature foreign policy concept of Xi Jinping’s New Era, written into both the Party (2017) and state (2018) constitutions.

BRI is a complex, evolving phenomenon that has changed its name and its direction many times since the original “New Silk Road” plan was introduced by Xi Jinping in late 2012.23 Its underlying logic, however, remains the same: to circumvent, and eventually replace, the post-War alliance system with a new Sinocentric “network of [bilateral] partnerships” (伙伴网) along an ever-expanding, mythologised “Silk Road” that now covers all continents (as well as outer space and cyberspace). The main policy tool driving this hyper-ambitious strategy is a new take on the notion of economic diplomacy.

BRI is a Beijing-initiated, Beijing-centred framework for its relationships with foreign states. Through a proliferation of BRI-themed events and entities, actively promoted by Party-led, state-funded organisations, the CCP seeks to engineer a global consensus around Xi’s policies. Presented domestically as an international endorsement of the Party and its leadership, this consensus is portrayed to foreign audiences as “multilateral”, “mutually beneficial”, “win-win”, using the Party’s propaganda tools and methods to mask a unilateral initiative.24

One of the darker sides of the BRI are corrupt practices by nominally private Chinese companies which nevertheless appear to act with the (at least) tacit approval of the authorities. CEFC, convicted in late 2018 of international corruption at the United Nations and in Africa, seemingly enjoyed, at least for some time, the support of China’s top leadership, as exemplified by the signature of their short-lived deal with Rosneft during Xi Jinping’s 2017 visit to Moscow,25 and the presence of the company’s representatives during Xi’s 2016 Prague visit.26

Similarly, after the change of government in Malaysia in 2018, minutes emerged from high-level meetings between the previous administration and representatives of Chinese companies involved in BRI projects in the country. According to the documents, inflated price tags were to guarantee “above-market profitability” for PRC state-owned companies involved in the projects. In one of the meetings, representatives of the PRC government reportedly offered surveillance and bugging of Wall Street Journal reporters in Hong Kong who had been covering then-PM Najib Razak’s 1MDB scandal. The incident illustrates the Party-state’s involvement in political activities, portrayed as purely economic and ‘multilateral’ for foreign consumption.

Minutes of the Chinese-Malaysian meetings say that although the projects’ purposes were “political in nature”—to shore up Mr. Najib’s government, settle the 1MDB debts and deepen Chinese influence in Malaysia—it was imperative the public see them as market-driven.27

These practices stretch the notion of economic diplomacy far beyond the scope of any faux amis promoted by the Party’s external propaganda.

In Europe, the region arguably most affected by economic diplomacy with Chinese characteristics is Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), grouped together by the PRC under its ‘16+1’ initiative.

16+1 as a spatial and political construct

Beijing’s “16+1” framework, now subsumed under Xi’s “Belt and Road” initiative, promised a trade and investment boom that failed to materialise, while testing the process of European integration.28

Old alliances and new partnerships on the EU’s Eastern flank

The establishment of the 16+1 ‘initiative’ in Warsaw in April 2012 institutionalised China’s influence build-up in Eastern Europe on a regional scale. The group brings together 16 post-Communist states in the region for a partnership with China. Officially, the full name is “Cooperation between China and the Central and Eastern European countries” (中国—中东欧国家合作), or “China – CEEC” for short. The 16 CEE countries form a geographic belt immediately adjacent to the post-Soviet space. (There are in fact 17 countries in this geographic area; since the PRC does not recognise Kosovo as an independent state, it is not included in 16+1.)

By forming the “CEE-China” group, Beijing in effect managed to realign a former Soviet backyard and current constituent part of the EU without much protest from either, and group it together with the Western Balkans, which had been outside the Soviet bloc and still lie partially outside the EU. How exactly this was achieved is yet to be fully examined. It seems that, initially, a major factor was the very vagueness of the initiative which, at least in the beginning, entailed few specifics. The original documents are full of lofty phrases like win-win, friendship and harmony, typical of the CCP’s external propaganda lingo, and contain no language that could be seen as potentially problematic.29 It is further stressed that “China-CEEC cooperation is in concord with [the] China-EU comprehensive strategic partnership”.30 There is anecdotal evidence that at least some CEE leaders did not quite understand what they were getting into.31

As with “economic diplomacy”, the PRC’s external messaging on its Eastern bloc initiative is hardly a faithful translation. Perhaps counterintuitively, 16+1 is not a regional bloc for the CEE countries to coordinate their policies towards China. Rather, it is a platform for sixteen bilateral relationships between Beijing and the individual CEE states, a much preferred arrangement for China to employ its diplomacy: in each bilateral relationship, the PRC is of course by default the bigger party.

Such bilateral arrangements are very much in line with the current Chinese diplomatic thinking for the “New Era”. The 19th CCP Congress in 2017 called for China to establish a global “network of partnerships” (伙伴网): instead of alliances, China will rely on “state to state contacts” (国与国交往).32 These bilateral partnerships will then cumulatively form a “Community of Common Destiny [or ‘Shared Future’] for Humankind” (人类命运共同体).33 An explanatory article in the People’s Daily claims that China has already established over a hundred such bilateral partnerships. The strategic line of “partnerships, not alliances” (结伴而不结盟) was supposedly put forward by Xi Jinping himself at the work conference on diplomatic work in 2014.34

Bilateral partnerships make it easier for China to go around, and cut across, existing alliances. 16+1 is a case in point. Instead of dealing with the EU as a whole, Beijing establishes relationships with individual countries, and arbitrarily puts them into an ad hoc regional grouping that ignores formal EU boundaries. (In 16+1, eleven countries are EU members while five are not.)

This new ad hoc group is again a collection of bilateral “partnerships”. Instead of coordinating to strengthen their collective bargaining position, CEE countries compete against each other to become Beijing’s favoured partner, and China’s proverbial “Gateway to Europe”.35

The ‘economic diplomacy’ of empty promises

At least part of the initiative’s lure has of course been “economic diplomacy”, or the prospect of Chinese investment and trade. The foundational idea of 16+1 was for CEE to tap into China’s economic potential, mostly by attracting Chinese investment.

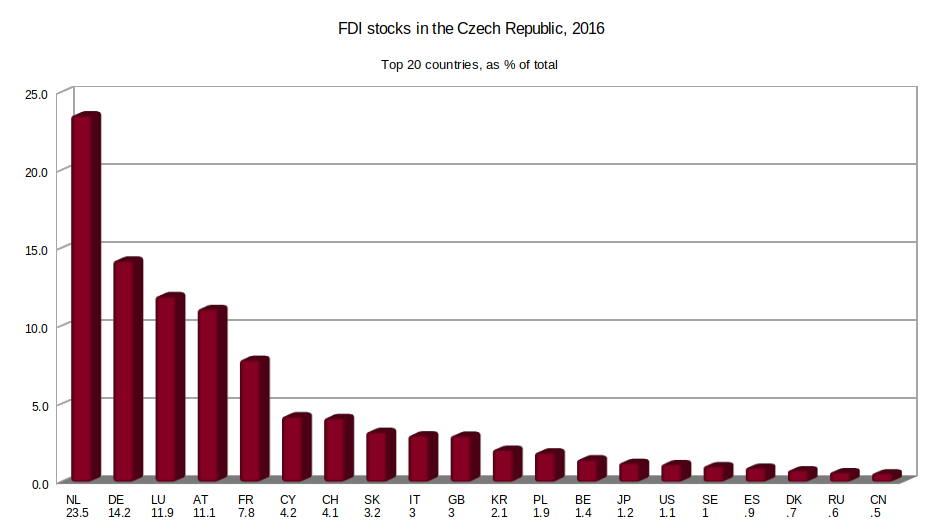

These expectations have not been fulfilled. The PRC’s investment in Europe has largely bypassed the region, with FDI flows into Eastern Europe limited to a few percent of the European total in recent years.36 In Poland, the region’s largest economy, Chinese FDI stocks had hardly exceeded a “mediocre” US$1bn by 2017, by the highest estimate.37 In the Czech Republic, the PRC accounts for a tiny fraction of total FDI stocks, behind over a dozen countries in Europe and Asia.38

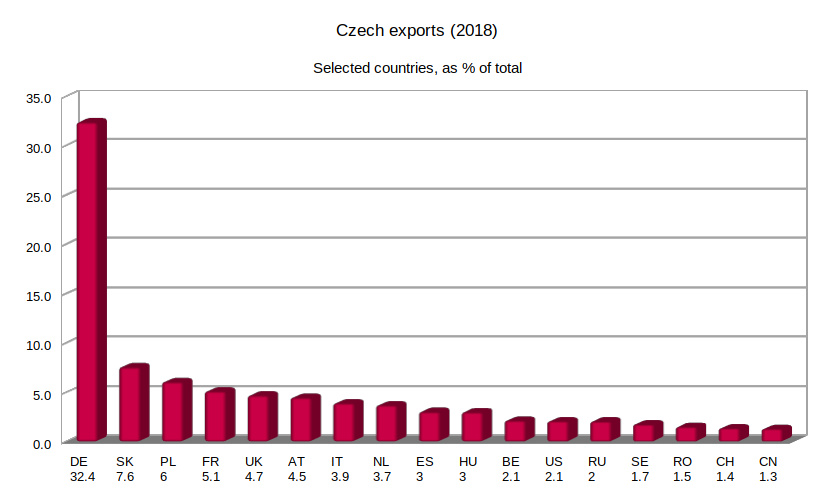

Trade relations have likewise failed to benefit the region. The Czech example perfectly illustrates the lack of economic foundation for an ostensibly economic ‘win-win’ partnership: China is the destination of only 1.3% of Czech exports (see figure), while imports from the PRC result in a trade deficit larger than the Czech surplus with its largest trading partner, Germany.39 The situation is hardly limited to the Czech Republic. The “sixteen” area’s trade deficit with China continues to grow, with imports from China increasing twice faster than imports between 2013 and 2017.40 The imbalance is not limited to the “Visegrad Four” (Hungary, Slovakia, Poland and the Czech Republic): while, according to preliminary data, in the Czech Republic Chinese imports exceeded exports to China by a factor of 10,41 in Serbia, one of the states most receptive towards Beijing’s initiative, the ratio is 24:1.42

Instead, the more tangible economic impact is the spillover of China’s own peculiar model of state capitalism characterised by institutionalised collusion between business and politics.43

Furthermore, in CEE, the ‘China Model’ collides with the EU way of doing business, and with specific EU regulations. The Belgrade – Budapest high-speed rail link, a flagship initiative of both 16+1 and BRI, offers an instructive example. The link is part of the Land Sea Express Route (陆海快线) meant to connect the Greek port of Piraeus, leased to China’s Cosco Pacific for 35 years in 2016, with Hungary. The final agreements were signed at the 16+1 summit in Riga in late 2016; the full details have not been disclosed. Shortly afterwards, an official inquiry into the project was initiated by the European Commission for suspected breach by Hungary of EU procurement regulations that require public tenders for large infrastructure projects.44

The pressure to bypass EU procurement regulations by political deals at 16+1 summits is not limited to one country. For instance, it was leaked to the press in the Czech Republic that China had also demanded in the run-up to the Riga summit that it be assigned a contract to finish the construction of the nuclear power plant in Dukovany without a public tender.45

This competition for Beijing’s favour among the 16 “partners” is partly a function of the grouping’s structure: 16+1 has a Secretariat in Beijing, where policies and projects are developed. The Secretariat is led by a PRC deputy minister of foreign affairs, with multiple Party-state agencies as “members”: notably, the Party’s propaganda system is represented, as are the CCP Youth League and its International Liaison Department (ILD).46 In the individual CEE countries, these projects are to be implemented through the local National Coordinators, typically vice-ministerial level government officials without relevant expertise or personnel support. The initiative is driven from China, with CEE countries effectively reduced to passive recipients of policies developed in Beijing. The whole structure resembles the larger Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), also a collection of bilateral partnerships under PRC stewardship toward a “common destiny”.

These examples illustrate one of the intrinsic problems of 16+1, at least for the 11 CEE countries that are also EU members. At the most basic level, 16+1, like BRI, represents a spill-over of the “China Model” into the Eastern flanks of the EU. Yet the China Model is in many aspects incompatible with EU legal and business practices, as well as its norms and values.

The EU model is based on (sometimes perhaps a little excessive) regulation designed to create an even field for open competition. The China Model mostly lies in no regulations at all; everything is open to ad hoc negotiations, preferably bilaterally at meetings and summits behind closed doors. EU economic integration has been driven by commercial factors, regulated by more or less transparent rules; China’s “Globalisation 2.0” is driven by political fiat.

Ironically, the very erosion of EU transparency and accountability regulations might be contributing to the Chinese initiatives’ attractiveness among some CEE elites. The less than overwhelming PRC investments are a case in point. The EU’s own infrastructure development programme has pumped many times more funds into the region. The EU funds come as grants, i.e., free money, whereas Chinese investment tends to materialise, if at all, as acquisitions or loans. Yet, China’s money is preferred by some, because it comes ‘with no strings attached’. In real life, this means that while EU funds are conditioned on strong transparency and accountability requirements, PRC money has no such ‘strings’ and can more readily feed into various patronage networks.

The Czech Republic: ‘Economic diplomacy’ as a byword for elite capture

The Czech Republic presents a rather striking case of the impact of “economic diplomacy” with Chinese characteristics on the political institutions of an EU member state. The case also illustrates the larger, indeed global ramifications of the PRC’s bilateral relationships with individual countries.

CEFC: The ‘flagship’ of political interference

The main actor on the Chinese side of the bilateral relationship was – until its collapse last year – the by now notorious Chinese company CEFC China Energy (中国华信能源), hailed at the time as “the flagship of Chinese investments in the Czech Republic”.47 The company’s chairman, Ye Jianming 叶简明, was even named an “honorary advisor” to Czech president Miloš Zeman in 2015. He still officially holds that position, even in his conspicuous absence after being disappeared a year ago, presumably investigated by the CCP’s disciplinary apparatus.

The CEFC affair is a prime example of the double messaging that underlies “economic diplomacy” in the region and beyond. Ostensibly a private company, CEFC was in fact linked to the CCP’s political influence machine,48 through the China Association for International Friendship Contact (CAIFC, 中国国际友好联络会), a front organisation within the PLA’s political warfare apparatus.49 The company’s Hong Kong think tank, further connected to the United Front system through former religious-affairs official Ye Xiaowen 叶小文, was at the centre of discourse-engineering efforts promoting BRI at the United Nations.50 The methods chosen, which included large-scale political corruption at the UN and in African countries, likely played a role in the company’s demise: the head of its non-profit arm has been convicted by a federal court in New York.51

The “flagship of Chinese investment” has been revealed, even in Chinese media, as a giant fraud and an elaborate Ponzi scheme that has accumulated billions of euros in debt in China and abroad.52 The story made the front pages of major international media last year; to the embarrassment of the Czech Republic, negative press coverage has featured an iconic photo of the Czech president with his now disappeared Chinese advisor.53

How could such a foreign policy fiasco occur in a stable and relatively prosperous EU member state? It is a cautionary tale of the corrosive effect “economic diplomacy with Chinese characteristics” can exert on the institutions of a newly democratic country in turbulent times of almost constant economic and political ruptures, from the global financial crisis to Brexit.

The Czech opening to China…

The Czech Republic made a dramatic U-turn in its policy towards China in 2013-2014, after the first directly-elected president Zeman took advantage of a rather banal government crisis to name his own ‘care-taking’ cabinet. Zeman’s cabinet ruled without parliamentary approval for more than half a year and prepared the ground for the official turn-around by the regular government that succeeded it in 2014.54

Both these cabinets were open to a group of pro-China lobbyists originally associated with Zeman’s Social Democratic Party (Česká strana sociálně demokratická, ČSSD) and since the early 2010s hired by PPF, the richest Czech financial conglomerate that emerged with substantial holdings from the privatisation process of the 1990s. For several years, PPF subsidiary Home Credit had been trying to build up their consumer-loan business in China. In 2010, they secured a limited licence for the city of Tianjin, as part of a pilot programme initiated by the Chinese government to stimulate domestic demand in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. Four cities were selected for this pilot programme, to be serviced by four different financial institutions. Home Credit was the only foreign one among them.

The success of the pilot project demonstrated the opportunities of a potential national licence. By their own accounts, Home Credit’s representatives were told by Chinese regulators that, for this to happen, the rather cool relationship between the two countries would need to improve. At that point, Home Credit started to hire former Czech politicians in an apparent effort to work towards that goal.

Most prominent among these politicians turned lobbyists was Jaroslav Tvrdík, a former Defence Minister.55 Tvrdík speaks no Chinese or English but, as a former minister and ČSSD insider, he had access to the political corridors back home. After Zeman was elected president in 2013, Tvrdík became his advisor and enjoyed full access to both the Zeman-nominated cabinet and the regular ČSSD-led government that replaced it in 2014.

In May 2014, the new China-friendly policy was officially declared during the Czech foreign minister’s Beijing visit. That same year, Home Credit indeed won the coveted national licence for their consumer loans business in what still was a very closed sector for foreign firms. Home Credit’s China venture suceeded beyond expectations: by 2017, its net loans in China were nearly €10bn, a 15-fold increase since 2014.56

…and China’s opening of the Czech Republic

Simultaneously, the Czech Republic opened up for Chinese ventures. The U-turn in the country’s China policy could not be justified by the success of one Czech company, especially since this particular firm is not incorporated (or taxed) in the Czech Republic, but in the Netherlands. The abrupt foreign policy turn was explained in terms of “economic diplomacy”, which became a favourite expression in President Zeman’s vocabulary. The Czech Republic would benefit as a whole by massive PRC investments that were to prop up the Czech economy.

The investment drive would be spearheaded by CEFC, which entered the scene in the autumn of 2015 with a series of eye-catching acquisitions, mostly prime real estate in Prague. This somewhat random shopping spree was advertised as just the beginning of the massive capital injection that was to follow. The Presidential Office, where CEFC Chairman Ye Jianming was secretly made an advisor half a year before the company even arrived in the Czech Republic,57 took the unusual step of listing the prospective investments on its website. In retrospect, only a fraction materialised, most of it financed by credit raised from a local Czecho-Slovak bank J&T (eventually re-financed, after CEFC’s collapse, by the Chinese state investment fund CITIC).58

Beyond the initial acquisitions, CEFC’s economic activities in the Czech Republic proved rather underwhelming. The company seemed more focused on developing political relationships by hiring a plethora of former politicians and civil servants, including a former high-ranking police investigator.59 Zeman’s China advisor and PPF lobbyist Tvrdík became the head of CEFC’s “European” headquarters in Prague. In a somewhat incestous circle, Tvrdík became the central hinge in an informal axis between PPF, CEFC, and the Czech state.60 One Miroslav Sklenář, originally in charge of protocol at the Prague Castle, distinguished himself by circulating through the revolving door between CEFC Europe and the Czech Presidential Office not once, but twice in three years.61 In late 2017, CEFC even hired the former Czech Euro-Commissioner for Enlargement, Štefan Füle.62 The Czech state seemed to be personally fusing with CEFC.

At the same time, CEFC appeared to go from strength to strength on the global scene. It was buying assets on several continents, and signed an agreement to buy a 14% stake in the Russian oil behemoth Rosneft.63 Chairman Ye Jianming kept collecting awards and distinctions: he became an advisor not only to Czech president Zeman, but also the UN General Assembly president Sam Kutesa;64 CEFC cultivated politicians from Serbia65 to Georgia.66 The company’s non-profit arm, also named CEFC in English, was awarded an affiliate status with the UN’s Economic and Social Council.

CEFC unravels…

And then it all unravelled, almost as fast as it had come together. In November 2017, the FBI arrested in New York the head of CEFC’s non-profit arm, former Hong Kong politician Patrick Ho (何志平), on charges of bribing politicians at the United Nations and in Africa. Shortly afterwards, CEFC Chairman Ye Jianming disappeared from public sight. On March 1, 2018, the respected Chinese financial portal Caixin revealed in a quickly censored article that the former head of a major state-owned CEFC partner had been detained by a local Commission for Disciplinary Inspection;67 Chairman Ye might himself be under inner-Party investigation.68 The often well-informed Hong Kong paper South China Morning Post claimed to have established from four Party sources that Ye’s detention had been ordered by Xi Jinping himself, apparently for embarrassing the Secretary General and his signature economic diplomacy initiative, the Belt and Road, which Ye Jianming and Patrick Ho both claimed to represent.69

The censored March 1 Caixin article also described in minute detail CEFC’s convoluted history and business model. According to this analysis, CEFC had been raising billions of dollars from PRC policy banks, chiefly the China Development Bank, by inflating the volume of its trade activities through fictitious transactions between its subsidiaries. Similarly, in the Czech Republic, CEFC financed its splashy acquisitions with credit from local banks like J&T.

After the arrest of Patrick Ho in New York and the disappearance of Ye Jianming in China, CEFC became unable to raise any more credit and quickly collapsed. Its distressed assets are being consolidated and sold off by the giant state investment fund CITIC. CITIC has also taken over the Prague-based CEFC Europe, but instead of closing it down, it keeps the shell alive, apparently for political expedience. Despite the heavy debt burden, the Czech politicians hired in various positions still appear to be collecting their hefty salaries, and some have been brought over to a new entity called CITIC Europe, which enjoys the same political support from the Prague Castle as CEFC before it.

…but the myth persists

Damage control for the CEFC fallout takes advantage of the very political connections that CEFC helped develop in its heyday. The various politicians directly hired or indirectly engaged by the bankrupt company now help spin a new narrative in which CEFC’s collapse was just the work of one faulty individual (Ye Jianming, who nevertheless retains his position as advisor to the Czech president). CITIC has now resolved CEFC’s “troubles”, and everything is back in order. The investments CEFC failed to deliver will be handed down by CITIC, or some other Chinese company, at some point. The strategy mirrors the CCP’s own: CEFC, a Party-linked entity that once excelled in the promotion of Xi’s geopolitical initiative, finds itself on the wrong side of the Party-led system after its methods were exposed.

The captured elite

The resilience of the “economic diplomacy” narrative despite the project’s obvious economic fiasco is a testimony to the efficacy of the kind of elite capture performed by CEFC. In the face of obvious facts, the political personalities engaged by the company perpetuate the narrative construct with slight modifications, reality be damned.

President Zeman took this tactic one step further by attacking the very institutions that had been warning against CEFC all along. The Czech counterintelligence agency BIS (Bezpečnostní informační služba) has been issuing veiled warnings against elite capture by Chinese entities for several years, as reflected in their public redacted yearbooks.70 These warnings have been not only ignored, but outright dismissed on a number of occasions.

Efforts to coopt the Czech elite went beyond such salient targets as president Zeman and his entourage. Less intuitively, CCP-linked entities often cultivate less senior figures whose support could become useful at a later point. The Czech Republic again offers a canonical example: a favourite interlocutor of the CCP International Liaison Department (ILD) is the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (Komunistická strana Čech a Moravy, KSČM), led by Vojtěch Filip, listed in Czechoslovak secret-police files as a collaborator.71 Although the ILD’s contacts go well beyond the local Communist party,72 its predilection for the KSČM exceeds the courtesy owed to a minor leftist force, and has even been visited on the KSČM youth wing.73 Old Communist ties aside, the ILD’s affection for the KSČM is part of its global “party-to-Party” efforts.74 As the next section will show, the Party-state can then count on the support of these contacts at critical junctures.

The BIS’s indirect warnings against CEFC have been vindicated, but the controversy flared up again in connection with the recent warnings by the Czech cyber security agency NÚKIB against Huawei.

The Huawei affair: Weaponising friendly contacts in times of crisis

The coordinated response to recent security warnings about Huawei in the Czech Republic and elsewhere illustrates the usefulness of the cultivated élite, which can be expected to spring to the defence of CCP-linked entities in times of crisis. The joint deployment of the domestic and external propaganda apparatus, the diplomatic corps and local ‘friendly’ politicians further shows the inadequacy of a Western-based understanding of the PRC Party-state-Army-market axis: an ostensibly private company can effectively function as a component of the Leninist political system.

The Czech Huawei warning

The Czech National Cyber and Information Security Agency (Národní úřad pro kybernetickou a informační bezpečnost, NÚKIB) issued a warning against the use of software and hardware products of Huawei, ZTE and their subsidiaries as a “threat against information security”.75 The warning mentioned the companies’ legal obligation to cooperate with intelligence activities76 and their known links to the state, as well as previous Czech intelligence warnings77 and the agency’s own knowledge of their local activity.

Open-source Chinese-language evidence and expert analysis supports the arguments invoked in the NÚKIB warning; other documented or alleged behaviour by Huawei reinforces these concerns.78

Western mistranslation phenomena, exploited by the PRC’s external propaganda, are also relevant to the Huawei case: analyses limited to technical aspects are insufficient unless informed by a knowledge of the political environment inhabited by such companies as Huawei. Views that reduce the international backlash against Huawei to a manifestation of recent US policy79 overlook similar concerns expressed over the years by researchers, journalists, commentators and politicians across the opinion spectrum, in multiple countries in Europe, Asia and Oceania. Even though the timing of the warning was likely linked to increased scrutiny of Huawei led by the US and its Five Eyes allies, the NÚKIB appears to have acted within its remit and in a way consistent with both previous Czech intelligence and international expert advice.80

The Party-state’s support for Huawei

The actions of the agency legally qualified to issue such warnings were met with a quick political response that, if anything, helped establish Huawei’s expansion abroad as an aspect of the PRC’s national interest. The swiftness of the reaction, which mobilised the CCP’s Propaganda and political influence apparatuses in support of Huawei’s own globally coordinated response, was taken in an early Sinopsis analysis as an attempt to preempt a domino effect in the CEE region, especially Poland, a key market. (Poland did indeed reveal shortly afterwards it was considering measures against the use of Huawei equipment.)81 Not a week after the NÚKIB warning, on the last Sunday before Christmas, the PRC ambassador in Prague sought and obtained a meeting with premier Andrej Babiš. The embassy’s account of the meeting, later contradicted by Babiš himself, described it as the Czech government’s humiliating subordination to the PRC’s defence of Huawei, with talk of Czech “efforts to rectify” the cybersecurity agency’s “mistakes”. Similar language was used by Xinhua news agency, which reported on the Czech government “correcting its mistake” on Huawei in a story signed by its senior Prague correspondent and quickly reproduced through the English-language Global Times.82 The swift intervention of both the Party-state’s foreign-affairs and propaganda organs to exert pressure on the Czech government suggests Huawei continues to function as a component of the PRC Party-led system and cannot be treated as a ‘private’ company in the Western sense.

The overlap between Huawei and the Party-state’s methods also includes ‘lawfare’ and discourse-engineering tactics. Huawei’s response to the recent wave of security concerns has included refloating a six-month old legal opinion, originally intended to fight regulations proposed by the US Federal Communications Commission, by lawyers from Zhong Lun 中伦, a well-connected Beijing law firm led by a Party member with United Front links. The opinion unsurprisingly dismisses concerns over Huawei’s duty to collaborate with PRC intelligence activities if requested. Again the proper context for such a document risks being lost in translation: contradicting the official Party line on matters of national security would be suicidal for a normal lawyer in a legal system where such behaviour routinely leads to disbarment, imprisonment and torture; an analysis at odds with the official line would be even more unlikely to come from the authors of the pro-Huawei document, one of whom has received a distinction as an “outstanding laywer Party member” (优秀律师党员). Huawei had the CCP-linked legal opinion reviewed by Clifford Chance, an international law firm with extensive operations in China, whose endorsement of it came with a disclaimer explicity rejecting its construal as a “legal opinion on the application of PRC law”. While keeping the document confidential, Huawei officers including its top executives in Poland and the Czech Republic took to citing the document as an “independent legal opinion” by a British firm.83 Such misrepresentation of the nature of the document, seeking to borrow the prestige of Western legal systems to present a message consonant with the CCP’s talking points, can again be seen as an example of discourse management through mistranslation. It can also be compared to “legal warfare”, one of the components of the People’s Liberation Army Three Warfares doctrine, which has indeed been applied in civilian contexts to earlier concerted efforts to counter foreign scrutiny of Party-state interests.84

Political interference at work: The captured elite to the rescue

Diplomatic and propaganda pressure was compounded with that exerted by local individuals ‘cultivated’ by the CCP. Two days after a Huawei executive was arrested in Poland on suspicion of spying for the PRC, and hours before the arrest was made public, Czech president Miloš Zeman devoted the beginning of his weekly interview with a (CEFC-funded) television station to a spirited defence of Huawei. Seemingly reading from notes, Zeman attacked the local intelligence services and warned of economic retaliation from the PRC. The PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs endorsed Zeman’s statements within hours; the unusual speed with which the MFA spokesperson was briefed about media statements in a small European country is again indicative of the level of priority the CCP attaches to the case.85

Another of the CCP’s main contacts in the country soon joined Huawei’s defence: Communist leader Vojtěch Filip briskly announced a Huawei-themed visit to China. Besides meeting with Huawei, Filip was received by Party and state officials in his official capacity as deputy speaker of the Chamber of Deputies, despite ostensibly travelling on a ‘private’ visit. Upon his return, Filip defended Huawei against the local cybersecurity agency in a series of convolutedly argued media interviews that generally agreed with the PRC’s positions on the case.86

National and EU-level institutional defence mechanisms are ill-prepared to respond to such activities enabled by United Front work, whose international expansion under Xi has begun to repurpose the political, institutional and economic systems of foreign countries into de facto CCP policy tools.87

The operational convergence of Huawei and CCP influence work is far from limited to the Czech Republic. Similarities to the developments discussed above can be found throughout Europe and elsewhere. The CCP-linked legal analysis has been cited in Huawei communications in Poland, Slovakia, the UK, Australia and the US.88 PRC state media attacked Poland’s arrest of a Huawei executive suspected of espionage as swiftly as it had reacted to developments in Prague, although less intensely.89 Huawei has now hired a former aide of Premier Morawiecki as an executive.90 One of Huawei’s main interlocutors in Polish politics, Marek Suski, has also repeatedly met with the CCP International Liaison Department.91

Although unsuccessful so far in overruling the concerns of the local agency, the simultaneous deployment of the CCP’s diplomatic, propaganda and foreign-influence tools to protect its interests as Czech developments threatened to snowball into regional scepticism shows the relevance of national-level influence work to supranational politics. In particular, elite capture in member states under the guise of economic diplomacy can have an impact on the EU as a whole.

Policy recommendations

- EU and member states’ relations with the PRC should seek a level playing field and maximum reciprocity in market access. EU member states should strive to coordinate their China policy to utilise their collective bargaining power, rather than compete with each other by entering into uneven bilateral relationships with the much larger PRC.

- Pan-European solidarity should be invoked whenever an individual member state is pressured by the PRC, for whatever reasons. The EU should also resist outside attempts at dividing the community by organising arbitrary sub-groupings of states or regions.

- Economic relations with the PRC should be free of political interference and manipulation. The practice of hiring former politicians and high-ranking civil servants for positions in foreign companies should be checked with codes of conduct, or legislation, if need be.

- Elite capture, the ultimate result of political influence activities, threatens to repurpose democratic institutions as tools of foreign authoritarian control. Member states should protect the integrity of their political systems through conflict of interest (CoI) legislation, especially for former government officials, a frequent target of these activities.

- Efficient investment screening mechanisms should be introduced, preferably at the EU level. Any such mechanisms can only be truly effective if political integrity is maintained. Ultimately, the investment risks will be defined by political decision-makers; should these be compromised, the whole process would be affected. Screening mechanisms should therefore go hand in hand with relevant CoI legislation.

- The EU and its member states should invest in rigorous, policy-relevant research on the nature of the PRC’s political and economic systems, including the Party links of non-state entities, using primary sources to understand its foreign policy objectives and tools. Tactics of political influence, in particular external propaganda and international United Front work, must receive the attention warranted by their central role in Xi Jinping’s administration.

Thanks to Nadège Rolland and Geoff Wade for comments on an early draft.

- Martin Hála and Jichang Lulu (2018), “The CCP’s model of social control goes global”, Sinopsis.↩

- V.I. Lenin (1920), Доклад Центрального Комитета на IX Съезде РКП(б), Полн. собр. соч. 40; Anne-Marie Brady (2008), Marketing Dictatorship: Propaganda and Thought Work in Contemporary China; Xinhua (2018), 习近平:举旗帜聚民心育新人兴文化展形象 更好完成新形势下宣传思想工作使命任务; Brady (2016), “Plus ça change ? : media control under Xi Jinping”, Problems of Post-Communism 64:3-4; Qian Gang (2018), “Signals from Xi’s speech on ideology”, China Media Project; John Garnaut (2017), “Engineers of the Soul: what Australia needs to know about ideology in Xi Jinping’s China”, via Sinocism.↩

- Brady, op. cit.; Mareike Ohlberg (2013), Creating a favorable international public opinion environment: external propaganda (duiwai xuanchuan) as a global concept with Chinese characteristics, University of Heidelberg; Jichang Lulu (2015), “China’s state media and the outsourcing of soft power”, CPI.↩

- Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 (1951), 全党重视做统一战线工作, 邓小平文选 1; Gerry Groot (1997), Managing transitions: the Chinese Communist Party’s united front work, minor parties and groups, hegemony and corporatism, University of Adelaide; Yan Mingfu 阎明复 (2011), 习仲勋与统战工作, 百年潮; Xinhua (2015), 习近平:巩固发展最广泛的爱国统一战线.↩

- Groot, op. cit.; Groot (2015), “The expansion of the United Front under Xi Jinping”, in The China Story Yearbook 2015; Anne-Marie Brady (2017), Magic Weapons: China’s political influence activities under Xi Jinping, Wilson Center; Groot (2018), “The rise and rise of the United Front Work Department under Xi” China Brief 18:7; John Dotson (2018), “The United Front Work Department in action abroad: a profile of the Council for the Promotion of the Peaceful Reunification of China”, China Brief 18:2; Jichang Lulu, “United Frontlings always win”, in Geremie Barmé, “The battle behind the front”, China Heritage.↩

- On the Czechoslovak version, cf., e.g., Karel Kaplan (2012), Národní fronta 1948–1960.↩

- Brady, op. cit.; Clive Hamilton and Alex Joske (2018), United Front activities in Australia, submission to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security.↩

- See, in the Czech Republic, Sinopsis (2018), “Jak Čína prosazuje v Česku svůj vliv. Z čínské provincie přes Olomouc až do Prahy”, Hlídací pes; Sinopsis and Jichang Lulu (2018), “My Name is Wu. James Wu. The United Front at work in the Czech Republic”, Sinopsis.↩

- Sinopsis (2017), “Vstane nová Kominterna”; Jichang Lulu and Martin Hála (2018), “A new Comintern for the New Era: The CCP International Department from Bucharest to Reykjavík”, Sinopsis; Julia G. Bowie (2018), “International liaison work for the New Era: generating global consensus?”, Party Watch Initiative.↩

- See “CEFC: The ‘flagship’ of political interference”.↩

- Jichang Lulu and Martin Hála (2019), “Huawei’s Christmas battle for Central Europe”, Sinopsis.↩

- Juan Pablo Cardenal (2018), “China’s elitist collaborators”, Project Syndicate; Cardenal (2018), “China seduce a golpe de talonario a las élites de América Latina”, El País.↩

- On the promotion of “multilateralism” as a task of external propaganda, see Sinopsis and Jichang Lulu (2018), “United Nations with Chinese Characteristics: Elite Capture and Discourse Management on a global scale”, Sinopsis.↩

- Similar policies had been tried several times before 1978, most notably in the form of “Four Modernisations” (四个现代化: agriculture, industry, national defense, and science and technology), first introduced in 1963 and then revived again in 1977 after Mao Zedong’s death. These early efforts had been stopped by Maoist hardliners. See Liu Guoxin 刘国新 (2010), 周恩来与四个现代化, via CPC News.↩

- Robert Zoellick (2005), “Whither China: from membership to responsibility?”, remarks to the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations.↩

- Keith Bradsher (2010), “Amid tension, China blocks vital exports to Japan”, The New York Times.↩

- Tania Branigan and Jonathan Watts (2012), “Philippines accuses China of deploying ships in Scarborough shoal”, The Guardian.↩

- Echo Huang (2017), “China inflicted a world of pain on South Korea in 2017”, Quartz. Nithin Coca (2018), “Chinese Tourists Are Beijing’s Newest Economic Weapon”, Foreign Policy.↩

- J. Michael Cole (2018), “Beijing ramps up pressure on foreign airlines, firms to respect China’s ‘territorial integrity’”, Taiwan Sentinel; Cole (2018), “Lufthansa, British Airways give in to Chinese pressure, list Taiwan as part of China”, Taiwan Sentinel; Jojje Olsson (2018), “Behind the scenes: how Sweden turned Taiwan into a ‘Province of China’”, Taiwan Sentinel; James Palmer and Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian (2018), “China threatens U.S. airlines over Taiwan references”, Foreign Policy; Olsson, “SAS viker sig genast då Kina hotar och bötfäller utländska företag över Taiwan”, InBeijing; Sui Lee-wee (2018), “Giving In to China, U.S. Airlines Drop Taiwan (in Name at Least)”, New York Times; Hamish Rutherford and John Anthony, “Air NZ plane forced to turn around after airline forgot to remove reference to Taiwan”, Stuff; Liberty Times 自由时报 (2018), 英航為我正名! 官網上「台灣」不再加註「中國」了.↩

- Renmin ribao 人民日报 (2018), 一以贯之增强忧患意识、防范风险挑战; Renmin ribao (2019), 参与全球经济治理体系变革.↩

- Li Hengjie 李恒杰 (2008), 论邓小平 “韬光养晦”的外交战略思想, 国际关系学院学报 3.↩

- China Cadre Learning Network 学习中国 (2017), 习近平首提“两个引导”有深意.↩

- On BRI, see Nadège Rolland (2017), China’s Eurasian Century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative, NBR.↩

- Sinopsis and Jichang Lulu (2018), “United Nations with Chinese Characteristics: Elite Capture and Discourse Management on a global scale”, Sinopsis; Wang Yiwei 王义桅 (2018), 西方质疑“一带一路”的三维分析——心理·利益·体系, 东南学术 1.↩

- Renmin wang (2017), 中国华信能源有限公司与俄罗斯基础元素集团签署长期互利合作总协定; TASS (2017), «Китайская CEFC получит опцию по покупке доли в розничном бизнесе “Роснефти”».↩

- Andrew Chubb (2017), “Pistons, PX, petroleum, politics: checking in with Chairman Ye Jianming”, South China Sea Conversations; CCTV (2016), 习近平同捷克总统泽曼举行会晤.↩

- Tom Wright and Bradley Hope (2019), WSJ Investigation: China Offered to Bail Out Troubled Malaysian Fund in Return for Deals, The Wall Street Journal.↩

- This section updates Martin Hála (2018), “China in Xi’s ‘New Era’: Forging a new ‘Eastern bloc’”, Journal of Democracy 29:2. Cf. Sinopsis (2017), “16 + 1”; Martin Hála (2016), “Evropa se rozpadá, Eurasie sílí”, Lidové noviny; Sinopsis (2016), “Jízda Evropou podle čínských pravidel”.↩

- Cf., e.g., the very generic declarations from the 2012 Warsaw summit: China-CEEC Secretariat (2012), “Wen outlines proposals on building closer China-Central and Eastern Europe ties”.↩

- Romanian Government news (2013), “The Bucharest Guidelines for Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries”.↩

- Personal communications with various Czech officials.↩

- Timothy R. Heath (2018), “China’s endgame: the path towards global leadership”, Lawfare.↩

- Nadège Rolland (2018), “Beijing’s vision for a reshaped international order”, China Brief 18:3.↩

- Zhong Sheng 钟声 (People’s Daily commentary, 2017), 走出一条国与国交往新路.↩

- Such an aspiration is of course not limited to CEE; the term has been used throughout the continent, including, and perhaps most enthusiastically, in the UK under David Cameron. Cf. Philip Hammond (2015), “UK-China: a global partnership for the 21st Century”, gov.uk; BBC (2015), “George Osborne on UK’s ‘golden era’ as China’s ‘best partner in the West’”.↩

- Thilo Hanemann, Mikko Huotari and Agatha Kratz (2019), “Chinese FDI in Europe: 2018 trends and impact of new screening policies”, Rhodium Group and MERICS.↩

- Łukasz Sarek (2018), Polsko-chińskie stosunki gospodarcze w 2017 r. w ujęciu porównawczym, Ośrodek Badań Azji Akademii Sztuki Wojennej; Sarek (2018), “Chinese FDI in Poland: Still just wishful thinking”, Sinopsis.↩

- See figure; cf. Tomáš Volf (2019), “Čínské investice v Česku pokulhávají za Zemanovými sliby”, Novinky.↩

- Ministerstvo průmyslu a obchodu (2019), “Zahraniční obchod 1-12/2018 – předběžné údaje r. 2018”.↩

- Sarek (2019), “The ‘16+1’ initiative and Poland’s disengagement from China”, China Brief 19:4.↩

- Ministerstvo průmyslu a obchodu, op. cit.↩

- Although the ratio, which was above 100 in the decade until 2014, has continued to decrease, Serbia’s trade deficit with China keeps growing (at a 21% rate in 2018 according to preliminary data). Based on data from the Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia.↩

- See “The Czech Republic: ‘Economic diplomacy’ as a byword for elite capture”.↩

- James Kynge, Arthur Beesley and Andrew Byrne (2017), “EU sets collision course with China over ‘Silk Road’ rail project”, Financial Times. A tender was eventually announced, at the time of the November 2017 16+1 Summit in Budapest. See Budapest Business Journal (2017), “Tender for Budapest-Belgrade rail upgrade published”; UIC News (2017), “Hungary/Serbia: Tender has been published for Budapest-Belgrade rail upgrade”; Zoltán Vörös (2018), “Who benefits from the Chinese-built Hungary-Serbia railway?”, The Diplomat.↩

- Ondřej Houska (2016), “Čína chce Dukovany naservírovat na talíři. Požaduje zakázku na dostavbu elektrárny bez výběrového řízení”, Hospodářksé noviny.↩

- The first 16+1 secretary, Song Tao 松涛, later became head of the ILD. See Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2012), “中国—中东欧国家合作秘书处召开地方和企业座谈会”; China-CEEC Secretariat (2015), “中国—中东欧国家合作秘书处秘书长”; China-CEEC Secretariat (2016), 中国—中东欧国家合作秘书处简介.↩

- Martin Hála (2018), “CEFC: Economic diplomacy with Chinese characteristics”, China Digital Times.↩

- Andrew Chubb and John Garnaut (2013), “The enigma of CEFC’s Chairman Ye”, South China Sea Conversations; Mark Stokes and Russell Hsiao (2013), The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department: Political Warfare with Chinese Characteristics, Project 2049 Institute; Aleš Rozehnal (2016), “Tvrdík popírá napojení svého šéfa na politické oddělení čínské armády. Tady je důkaz”, Hlídací pes; Olga Lomová (2016), “Czech-Chinese honeymoon II”, Visegrad Revue; Sinopsis (2016), “I informace se musejí točit. Být, či nebýt v CAIFC?”.↩

- Michael D. Swaine (1998), The role of the Chinese military in national security policymaking, RAND; David Shambaugh (2002), “China’s international relations think tanks: evolving structure and process”, The China Quarterly 171; Stokes and Hsiao, op. cit.↩

- Hála, “CEFC: Economic diplomacy…”; Sinopsis and Jichang Lulu (2018), “United Nations with Chinese Characteristics: Elite Capture and Discourse Management on a global scale”, Sinopsis.↩

- US Department of Justice (2018), Patrick Ho, former head of organization backed by Chinese energy conglomerate, convicted of international bribery, money laundering offenses.↩

- Ji Tianqin 季天琴 (2018), 叶简明被调查中国华信命运如何?, Caixin; translation by Andrew Chubb, “Ye Jianming under investigation, what fate will befall CEFC?”, South China Sea Conversations.↩

- Cf. David Barboza, Marc Santora and Alexandra Stevenson (2018), “China seeks influence in Europe, one business deal at a time”, The New York Times.↩

- Martin Hála (2014), “Náš krteček v Pekingu”, Lidové noviny.↩

- Martin Hála (2015), “Krtek a panda na hrad!”, Hospodářské noviny.↩

- Lenka Ponikelska and Krystof Chamonikolas, “Czech billionaire could get caught up in Huawei spying scandal”, Bloomberg.↩

- Renmin wang (2015), 中国华信董事局主席叶简明任捷克总统经济顾问.↩

- On CITIC, cf. Ondřej Klimeš (2018), “CITIC vede Česko do nové éry čínského vlivu: vstříc Velkému skoku vzad a exportu leninského autoritářství”, Deník N.↩

- Sinopsis (2016), “Elitní český policista ve službách CEFC”.↩

- Martin Hála (2017), “Letadlová loď do Eurasie: Obraz totálního zhroucení”, “Letadlová loď do Eurasie 2: Česká republika na Hedvábné stezce”, Hlídací pes.↩

- Sinopsis (2016), ”Škatulata, hejbejte se!”.↩

- Hospodářské noviny (2017), “Bývalý komisař Füle se stane třetím členem dozorčí rady CEFC, která v Česku vlastní i Slavii”.↩

- Dmitry Kozlov (2017), “Glencore вознаградят за «Роснефть»”, Коммерсантъ.↩

- Sinopsis and Lulu, op. cit.; Zhongguo wang via Tencent Finance (2015), 中国华信董事局叶简明主席会见69届联大主席.↩

- Sinopsis and Lulu, “United Nations with Chinese characteristics”.↩

- Tinatin Khidasheli and Sinopsis (2018), “Georgia’s China Dream: CEFC’s last stand in the Caucasus”, Sinopsis.↩

- Ji Tianqin 季天琴 (2018), 叶简明被调查中国华信命运如何?, trans. Chubb, Soutch China Sea Conversations.↩

- Sinopsis (2018), “Šuang-kuej: stranická inkvizice bez opory v zákoně”; Český rozhlas (2018), “Kam zmizel Zemanův čínský poradce? ‘Vyšetřování stranou je tajný proces,’ líčí sinolog”.↩

- Eric Ng and Xie Yu (2018), “China detains CEFC’s founder Ye Jianming, wiping out US$153 million in value off stocks”, SCMP. On Ye Jianming’s detention, cf. also Zhao Yibo 赵毅波 (2018), 叶简明被指行贿甘肃原省委书记王三运, 北京报网; Liu Shengjun 刘胜军 (2018), 叶简明的套路, 金融界.↩

- BIS (2015), Výroční zpráva Bezpečnostní informační služby za rok 2014; BIS (2016), Výroční zpráva Bezpečnostní informační služby za rok 2015; BIS (2018), Výroční zpráva Bezpečnostní informační služby za rok 2017. On the BIS warning on ILD activity, cf. Lulu and Hála (2018), “A new Comintern for the New Era”.↩

- MF DNES, Radek Kedroň and Václav Dolejší (2003), “Poslanci Filipovi říkali u StB Falmer”, iDNES.↩

- Sinopsis (2016), “Zeman a Hamáček: Čína, náš vzor”.↩

- Jaroslav Ošťádal (2015), ”Čínský sen – zpráva o návštěvě ČLR”, KSČM Hradec Králové.↩

- Jichang Lulu and Martin Hála (2018), “A new Comintern for the New Era: The CCP International Department from Bucharest to Reykjavík”, Sinopsis; Jichang Lulu (2018), “New Zealand: United Frontlings bearing gifts”, Sinopsis.↩

- NÚKIB (2018), Várování 3012/2018-NÚKIB-E/110.↩

- For relevant PRC legislation and analysis, Ondřej Klimeš (2019), “Mýty o Huawei, mýty od Huawei. Co můžeme věřit čínské firmě, před níž varuje nejen BIS”, Deník N; 《中华人民共和国国家情报法》, NPC (full text and Czech translation in Olga Lomová (2019), “Čínský zákon o celonárodní špionáži”, Sinopsis); Samantha Hoffman and Elsa Kania (2018), “Huawei and the ambiguity of China’s intelligence and counter-espionage laws”, ASPI.↩

- BIS (2014), Výroční zpráva Bezpečnostní informační služby za rok 2013.↩

- Jichang Lulu and Martin Hála (2018), “Huawei’s Christmas battle for Central Europe”, Sinopsis; Danielle Cave (2018), “The African Union headquarters hack and Australia’s 5G network”, The Strategist; Joan Tilouine and Ghalia Kadiri (2018), “À Addis-Abeba, le siège de l’Union africaine espionné par Pékin”, Le Monde; US Department of Justice (2019), “Chinese telecommunications device manufacturer and its U.S. affiliate indicted for theft of trade secrets, wire fraud, and obstruction of justice”.↩

- For an assessment of such reductionism to recent American policy, see “Huawei, national security and US-China tech wars”, in Łukasz Sarek (2019), “Arresting Huawei’s march in Warsaw”, Sinopsis.↩

- More references in Lulu and Hála, “Huawei’s Christmas battle for Central Europe”.↩

- Lulu and Hála, op. cit.; Sinopsis (2019), “A new front opens in Huawei’s battle for Central Europe”; Sarek, “Arresting Huawei’s march in Warsaw”.↩

- Wang Yi 王义 (2018), 捷克政府纠正针对华为手机的错误做法, Xinhua; Wang Yi (2018), “Czech security council refutes warning from its cyber-watchdog over Huawei”, Global Times.↩

- Sinopsis and Jichang Lulu (2019), “Lawfare by proxy: Huawei touts “independent” legal advice by a CCP member”, Sinopsis.↩

- Ondřej Klimeš (2019), “Mýty o Huawei, mýty od Huawei”. On CEFC and ‘lawfare’ in the Czech Republic, Martin Hála (2016), “Právní bojovníci na mediální frontě”, Sinopsis. On the Three Warfares, see also Mark Stokes and Russell Hsiao (2013), The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department: Political Warfare with Chinese Characteristics, Project 2049 Institute; Elsa Kania (2016), “The PLA’s latest strategic thinking on the Three Warfares”, China Brief 16:3; Peter Mattis (2018), “China’s ‘Three Warfares’ in perspective, War on the Rocks; John Dotson (2019), “Beijing sends a menacing message in its Lunar New Year greeting to Taiwan”, China Brief. For the application of the concept to the ruling against PRC’s South China Sea claims, Chen Xulong 陈须隆 (2016), 年中国际观察:国际格局加速演变, 瞭望 29; Diyi caijing 第一财经 (2016), 专访朱锋:应对南海仲裁,中国要打好这‘三大战役’. Cf. Michael Clarke (2019), “China’s application of the ‘Three Warfares’ in the South China Sea and Xinjiang”, Orbis.↩

- Sinopsis (2019), “A new front opens in Huawei’s battle for Central Europe”; TVP Info (2019), Chińczyk i były oficer ABW zatrzymani. ‚Podejrzani o współpracę z obcym wywiadem‘”; TV Barrandov (2018), Týden s prezidentem 10.01.2019; PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2019), 2019年1月11日外交部发言人陆慷主持例行记者会.↩

- Sinopsis and Jichang Lulu (2019), “The importance of Friendly Contacts: the New Comintern to Huawei’s rescue”, Sinopsis.↩

- On the case of New Zealand, see Anne-Marie Brady (2017), Magic Weapons: China’s political influence activities under Xi Jinping, Wilson Center; Jichang Lulu (2018), “New Zealand: United Frontlings bearing gifts”, Sinopsis.↩

- Sinopsis and Lulu (2019), “Lawfare by proxy: Huawei touts “independent” legal advice by a CCP member”; Klimeš, “Mýty o Huawei, mýty od Huawei”; Tonny Bao, “This is Huawei, a reliable partner”, Huawei; Money.pl (2019), “Stawką 8,5 mld euro i najpilniej strzeżona tajemnica Chińczyków”; Lukáš Zachar (2019), “Huawei reaguje: TOP 5 vecí, o ktorých sa klame, takáto je pravda!”, Techbyte; Matěj Čuchna (2019), “[Radosław Kędzia], Huawei: NÚKIB s námi už dva roky pořádně nekomunikuje”, ChannelWorld; Ryan Ding (2019), “Re: Security of the UK’s communications infrastructure, letter to the UK House of Commons; Andrew Orlowski (2019), “Huawei pens open letter to UK Parliament: Spying? Nope, we’ve done nothing wrong”, The Register; Zhou Hanhua 周汉华 (2019), “Chinese government can’t force Huawei to make backdoors”, Wired.↩

- Sarek, “Arresting Huawei’s march in Warsaw”.↩

- Bartek Godusławski (2019), “Huawei chce dotrzeć do Morawieckiego. Pomóc ma Ryszard Hordyński”, Gazeta Prawna. On Huawei ‘localised’ elite recruitments, cf., e.g., Martin Thorley (2019), “Huawei founder’s protests mean nothing – independent Chinese companies simply don’t exist”, The Conversation.↩

- Lulu and Hála, “Huawei’s Christmas battle for Central Europe”.↩